Stakeholders

Purpose

Understanding stakeholders is essential for making ethical business decisions. Stakeholders are individuals, groups, or organizations who can affect, or are affected by, an organization’s actions, policies, and outcomes. By identifying and analyzing stakeholders, decision-makers can better understand the potential impacts of their actions, prioritize engagement, and choose strategies that promote fairness, accountability, and trust.

Two well-known models offer systematic approaches to stakeholder analysis:

- Savage et al. (1991) Stakeholder Typology

- Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997) Stakeholder Salience Model

Key Concepts

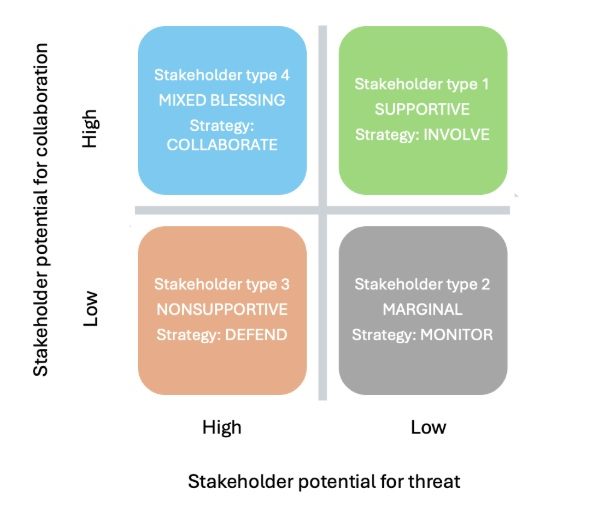

Savage et al. (1991) Model

The Savage et al., 1991 model for stakeholder analysis is a diagnostic typology of organizational stakeholders. This model is designed to help executives assess and manage organizational stakeholders by classifying them based on two key dimensions:

- Stakeholder’s Potential for Threat to Organization: This dimension assesses how much a stakeholder could potentially harm the organization.

- Stakeholder’s Potential for Cooperation with Organization: This dimension assesses how much a stakeholder could potentially cooperate with the organization.

By analyzing these two dimensions (high or low for each), the model identifies four generic types of stakeholders, each associated with a specific management strategy:

- The Supportive Stakeholder

- Characteristics: These stakeholders have a low potential for threat to the organization and a high potential for cooperation. They are considered “ideal stakeholders” whose goals and actions align with the organization’s mission. Examples include well-managed organizations, boards of trustees, managers, employees, parent companies, suppliers, service providers, and non-profit community organizations.

- Strategy: The recommended strategy is to involve them. Executives should involve supportive stakeholders to maximize and encourage their cooperative potential.

- The Marginal Stakeholder

- Characteristics: These stakeholders have a low potential for threat and a low potential for cooperation. They are not considered strategically important and can often be ignored.

- Strategy: The recommended strategy is to monitor them. Executives should monitor marginal stakeholders but not make them a high priority, as their interests are narrow, and their impact is minimal.

- The Non-supportive Stakeholder

- Characteristics: These stakeholders have a high potential for threat to the organization and a low potential for cooperation. They are considered dangerous and may represent significant forces affecting the organization. Examples can include large competing organizations, trade unions, government, and media.

- Strategy: The recommended strategy is to defend against them. Executives should adopt a defensive strategy to minimize the threat posed by nonsupportive stakeholders.

- The Mixed Blessing Stakeholder

- Characteristics: These stakeholders have a high potential for threat and a high potential for cooperation. They are major stakeholders, like employees or customers, who have the capacity to both cooperate with and threaten the organization.

- Strategy: The recommended strategy is to collaborate with them. Executives should aim for maximal cooperation by working closely with these stakeholders, recognizing their dual nature.

This typology, illustrated as a 2×2 matrix, helps managers identify the appropriate generic strategies for managing different stakeholders based on their potential for cooperation and threat.

Reference: Savage, G. T., Nix, T. W., Whitehead, C. J., & Blair, J. D. (1991). Strategies for assessing and managing organizational stakeholders. Academy of management perspectives, 5(2), 61-75.

Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997) Model

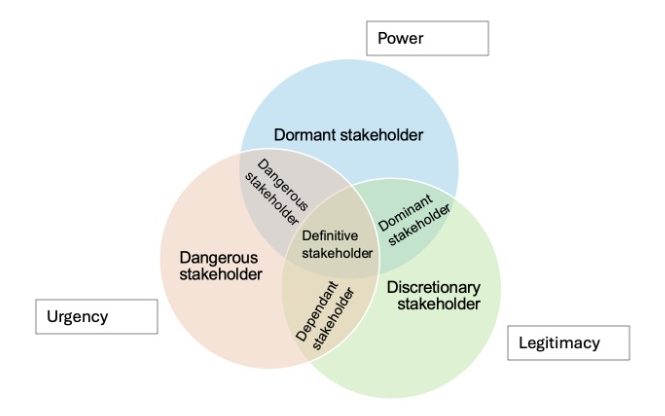

The model for stakeholder analysis, as proposed by Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997), aims to develop a comprehensive theory for stakeholder identification and salience, addressing the fundamental question of “who and what counts” for a firm. This model provides a systematic way to categorize and understand the importance of various stakeholders to managers.

The core of the model is based on three key attributes that stakeholders may possess or be perceived to possess:

- Power: Defined as the probability that one actor can carry out its will despite resistance, or the ability of actor A to get actor B to do something B would not otherwise have done. Power can be:

- Coercive: Based on physical resources (e.g., force, violence, restraint).

- Utilitarian: Based on material or financial resources (e.g., goods, services, money).

- Normative: Based on symbolic resources (e.g., prestige, esteem, love, acceptance).

- Power is a variable attribute, not a steady state, and can be acquired or lost.

- Legitimacy: Defined as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions“. It is a desirable social good and can be defined at individual, organizational, or societal levels. Legitimacy is distinct from power and can exist independently. It is also a variable and dynamic attribute.

- Urgency: Defined as the degree to which stakeholder claims call for immediate attention. Urgency exists when two conditions are met:

-

- Time sensitivity: Managerial delay in addressing the claim is unacceptable to the stakeholder.

- Criticality: The claim or relationship is highly important to the stakeholder. This criticality can stem from ownership of firm-specific assets, sentiment, expectation, or exposure to risk. Urgency is a perceptual phenomenon and can vary over time.

Attributes as Variables: Each attribute is dynamic and can change for any entity or stakeholder-manager relationship. Their existence or degree is based on multiple perceptions, making it a constructed reality. Furthermore, an entity might not be conscious of possessing an attribute or choose not to enact implied behaviours.

The model posits that the salience of a stakeholder—the degree to which managers give priority to competing stakeholder claims—is positively related to the cumulative number of these attributes perceived by managers. This leads to a typology of stakeholder classes and non-stakeholders:

- Non-Stakeholders/Potential Stakeholders: Entities with no power, legitimacy, or urgency are not considered stakeholders and hold no salience for managers.

- Latent Stakeholders (Low Salience): Possess only one attribute. Managers may do little about them and might not even recognize their existence, and these stakeholders are unlikely to give attention to the firm.

- Dormant Stakeholders (Power only): They have the power to influence but lack a legitimate relationship or urgent claim, so their power remains unused. Managers should be cognizant of them due to their potential to acquire another attribute. Examples include fired employees who might later use coercive, utilitarian, or symbolic power.

- Discretionary Stakeholders (Legitimacy only): They have legitimacy but no power or urgent claims. They are often recipients of corporate philanthropy, and managers are under no pressure to engage actively with them.

- Demanding Stakeholders (Urgency only): They have urgent claims but lack power and legitimacy. They are seen as bothersome but not dangerous or warranting significant management attention, as the “noise” of urgency alone is insufficient for high salience.

- Expectant Stakeholders (Moderate Salience): Possess two attributes. This combination leads to a more active stance from the stakeholder and increased firm responsiveness.

- Dominant Stakeholders (Power + Legitimacy): They are powerful and legitimate, forming the “dominant coalition” within the firm. Their expectations “matter” to managers, and they often have formal mechanisms (e.g., boards of directors, investor relations) in place to acknowledge their importance.

- Dependent Stakeholders (Legitimacy + Urgency): They have urgent and legitimate claims but lack power. They depend on other, more powerful stakeholders or management benevolence for their claims to be addressed. An example is local residents and the environment affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill, whose claims became salient through the advocacy of dominant stakeholders like the government.

- Dangerous Stakeholders (Power + Urgency): They are powerful and have urgent claims but lack legitimacy. These stakeholders can be coercive and potentially violent, acting outside legitimate bounds (e.g., wildcat strikes, sabotage, terrorism). While their actions are abhorred, identifying them is crucial for preparedness and mitigation.

- Definitive Stakeholders (High Salience): Possess all three attributes: power, legitimacy, and urgency.

- When a stakeholder from the dominant coalition has an urgent claim, managers have a clear and immediate mandate to prioritize it.

- Examples include stockholders of major companies (e.g., IBM, GM) who became active and caused managerial changes when their stock values plummeted, signalling urgency.

- Any expectant stakeholder can become definitive by acquiring the missing attribute, such as the African National Congress (ANC) moving from a demanding, then dangerous, to a dependent (by gaining legitimacy through external support), and finally a definitive stakeholder (by gaining power through elections). Similarly, dependent workers can become definitive by aligning with powerful stakeholders like unions and courts.

Managerial Role and Dynamism:

Managers play a central role in this theory as they are at the nexus of contracts and have direct control over decision-making. It is the managers’ perception of these attributes that determines which stakeholders become salient and receive their attention. Managerial characteristics, such as environmental scanning practices and values, can moderate these perceptions.

The model emphasizes the dynamic nature of stakeholder-manager relationships. Stakeholder attributes are not static; they can change, leading stakeholders to shift between classes and altering their salience to managers. This dynamism means that managers need to constantly monitor and adapt their strategies.

In essence, this model provides a robust framework for managers to not only identify their stakeholders but also to understand the degree of attention they should, and likely will, pay to each, based on the interplay of power, legitimacy, and urgency.

Reference: Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of management review, 22(4), 853-886.

In Practice

Example Scenario

At NexaTech, the leadership team is evaluating a proposal to close its rural Nova Scotia customer service center and replace it with AI chatbot technology. The plan could significantly reduce operating costs, but employees, community leaders, and some customers have expressed concerns about job loss, declining service quality, and the economic impact on the rural community.

Using the Savage et al. model, the leadership might identify:

- Rural community leaders as Mixed Blessing stakeholders. They are willing to collaborate on economic development solutions but could also mobilize opposition if the center is closed.

- The AI technology vendor as a Supportive stakeholder. They are highly cooperative and invested in the project’s success.

- Employee unions as Non-Supportive stakeholders. They may resist the transition due to job loss concerns.

Using the Mitchell et al. model, the team might identify:

- Current customer service employees as Dependent stakeholders. They have legitimate and urgent concerns about job security but limited direct power, relying on public support or union advocacy to be heard.

- Key corporate clients as Definitive stakeholders. They hold purchasing power, have a legitimate relationship, and their urgent concerns about maintaining service quality give them high priority in the decision-making process.

Applying these models helps NexaTech assess not only who will be most affected but also whose influence and needs must be addressed before moving forward.

Tips and Tools

- Regularly update stakeholder assessments because influence and priorities can shift quickly.

- Use both models together. Savage helps define engagement strategies, while Mitchell helps set priorities.

- Look beyond the obvious and include groups who may not currently have power but could gain it.

- Engage early and often because proactive communication can turn potential threats into cooperative relationships.

Next Step

You’ve just completed an essential part of the ethical decision-making process. Taking the time to work through this thoughtfully ensures a stronger foundation for the choices that follow. Ethical decisions are rarely simple; they require careful attention to detail, values, and context.

When you’re ready, continue to the next part of the process.

Proceed to the next stage: STAGE 3. CHOOSE THE BEST PATH FORWARD →