4 Clinical Interviewing and Observation

Anna MacGillivray and Tim Naerebout

Imagine you’re catching up with a friend over coffee. You ask how they’ve been, what’s new in their relationship, and how work is going. The conversation flows naturally, sometimes serious, sometimes light, and you respond with warmth, curiosity, and maybe a few shared laughs. Now, imagine sitting across from someone in your office as a clinical psychologist. You might ask some of the same questions about relationships, work, and stress, but the context is entirely different. A clinical interview is not just a conversation; it’s a structured, intentional process designed to gather information, build rapport, and begin understanding a person’s psychological world.

By the end of the chapter you should be able to:

- Define clinical assessment and identify its primary goals.

- Explain the informed consent process and its ethical importance.

- Compare and contrast structured, semi-structured, and unstructured interviews, including their limitations.

- Define behavioural observation and identify its challenges.

- Identify the benefits and limitations of self-monitoring for both clients and clinicians.

- Identify examples of cultural bias and microaggressions and explain their impact on clinical interviewing.

Introduction

When working as a clinical psychologist, one of your main tasks might be to help understand and develop solutions to problems or challenges a client may be facing. The first step to reaching that goal is assessment. This is where information is gathered in order to help create as complete a picture of the client as possible, which is essential when identifying or defining their challenges. The most common way psychologists do this is through clinical interviewing and behavioural observation. By talking to an individual or observing them, we gather data on how they act, think or behave; it helps to understand a client’s situation better, see their perspective and then draw conclusions to define the challenges they are facing.

While clinical interviews resemble everyday conversations, they differ significantly in their goals, content and boundaries. Unlike a casual dialogue or job interview, clinical interviews are guided by professional standards and tailored to the needs of the assessment or treatment. The word interview comes from the 16th-century word entrevue, meaning “to glimpse or to see each other.” An interview can be described as a meeting in which one person learns information from another. It is important to note that the person being interviewed (the interviewee) is not always the client receiving treatment. In some cases, such as with children, individuals with cognitive impairments or in couples/family therapy, a caregiver or significant person may provide information as part of the clinical interview. Interviewers need to be trained in particular skills to help improve the effectiveness of the interview. This includes asking open or closed-ended questions, leading to different kinds of responses that may invite a client to elaborate or answer with a yes-no answer (Lee & Hunsley, 2017; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Furthermore, interviewers will pay special attention to both non-verbal and verbal techniques to reassure the client, improve comfort, demonstrate understanding, and make sure the interviewee feels heard (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2014).

Depending on the interview’s structure and goals, it can serve multiple purposes that are highly beneficial to clinicians, chief among which is building rapport with the client (Pashak & Heron, 2022). When building rapport, a relationship is developed between the client and clinician, which helps create a safe environment for clients to share their thoughts and feelings openly. The types of questions and how they are asked can deeply influence the nature and strength of that relationship, either hindering or enhancing the ability for the psychologist to understand the client’s situation (Pashak & Heron, 2022). Interviews are also often an ideal place for behavioural observation. Although the nature of an interview is typically verbal, a skilled interviewer will also pay close attention to a client’s appearance and behaviour to gain an understanding that goes deeper than only the words that are communicated; even interviewing digitally or over the phone, much can be learned based on a clients tone, their pauses or their reactions to questions or comments (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2014).

A clinical psychologist needs to be aware of many things when conducting an interview. A client might try to manipulate the interview to gain a desirable outcome by selectively disclosing information, exaggerating, minimizing significant details, or deliberately fabricating information (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2014). It takes a skilled and neutral interviewer to address and account for these behaviours and to use them when developing an assessment and an effective solution.

Beyond individual behaviours, external factors such as culture, age, and gender also impact the interviewing process and need to be considered (Mohlman et al., 2012; Segal et al., 2010). For example, it has been demonstrated that children behave and respond during interviews significantly differently from that of adults (Lee & Hunsley, 2017). This does not imply that children are unreliable sources of information; rather, it highlights the necessity of tailoring interview techniques to align with their cognitive development and emotional expression. Adjustments in question phrasing, pacing, and interpretation are essential to ensure that the information gathered is both accurate and meaningful. While adapting to the unique circumstances of each interview is vital for effectiveness, it is equally important to recognize that all clinical interviews must be grounded in a strong ethical framework.

Ethical Foundations

Psychologists are guided by ethical codes, such as those outlined by the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA; 2017). The code of ethics helps to protect clients by helping ensuring psychologists’ ethical behaviour and attitudes (CPA, 2017). For example, as outlined in Pillar 1, Respect for the dignity of persons and peoples, psychologists are required to keep what is revealed during psychological services confidential. Confidentiality is especially important during a clinical interview, when the client may be sharing vulnerable details about their life for the first time. This confidentiality is crucial to the therapeutic relationship, promoting trust and a safe space to share. In certain situations, however, psychologists can ethically (or are legally required to) break this confidentiality. Limits of confidentiality, refer to the situations in which a psychologist is obligated to break confidentiality and disclose patient information to another person or agency (CPA, 2017).

One clear example of a limit of confidentiality arises when a client poses an immediate risk of harm to themselves or others, particularly when they express a specific plan and intent to act. In these cases, psychologists are ethically (and often legally) required to intervene, guided by Pillar 2 of the Code of Ethics, Responsible Caring. This scenario presents as an ethical dilemma between Pillar 1 (Respect for the Dignity of Persons, which includes confidentiality) and Pillar 2, as the psychologist must balance the duty to protect confidentiality and the imperative to minimize harm. In these cases, the psychologist would ethically prioritize the client’s safety over maintaining confidentiality, even though the disclosure occurred within a confidential therapeutic relationship. Ideally, such limits to confidentiality are clearly outlined during the informed consent process at the outset of treatment, ensuring that clients are aware of these exceptions and are not caught off guard should intervention become necessary.

Similarly, psychologists have an ethical and legal obligation to report suspected or disclosed instances of abuse or neglect of children, the elderly, or any vulnerable population. For example, under Section 24 of the Nova Scotia Child and Family Services Act (2022), any professional working with children must immediately contact child welfare if they have reasonable grounds to suspect that a child is in need of protection. This duty to report is not optional and supersedes the usual expectations of confidentiality. Importantly, psychologists are held to a higher standard than the general public due to their professional role and training. While all Canadians are legally required to report suspected child abuse (e.g., Section 23 of the Child and Family Services Act in Nova Scotia), professionals like psychologists are expected to recognize more subtle signs of harm and act promptly. For example, if a child discloses ongoing physical abuse during a clinical interview, the psychologist must report this immediately, triggering an investigation by child protection services to ensure the child’s safety. In cases where legal proceedings follow, psychologists may be required to release clinical records and even testify in court. These responsibilities underscore the importance of clearly communicating the limits of confidentiality during the informed consent process, so clients understand that disclosures involving safety concerns may necessitate legal reporting.

Therapist: Before we begin, I want to explain how confidentiality works. What we talk about here stays between us. I won’t share what you say with anyone else unless you give me permission. That’s part of making this a safe and private space for you.

But there are a few exceptions. I’m required to break confidentiality if:

- I believe you or someone else is in immediate danger,

- You tell me about a child or vulnerable person being hurt, or

- A court asks me to share information through a legal process.

I’ll always try to talk with you first if any of these situations come up. Do you have any questions about that?

The client has a right to know when and why confidentiality will be broken. This is why it is important that both the psychologist and client properly understand the limits of confidentiality. It is critical for the psychologist to inform clients about these limits, typically during the informed consent process. The informed consent process is an integral part of helping the client understand the nature of your relationship with them, including the limits before a clinician can start building the rapport and trust on which the interview process relies.

Foundational Interview Skills

Clinical assessment requires a variety of skills that enable psychologists to gather accurate and meaningful information, develop a strong therapeutic relationship, and document key findings. The single most important ingredient in a good clinical interview is rapport, which refers to the therapeutic alliance between the clinician and the client. Rapport is achieved via an attitude of acceptance, understanding, and respect, unconditional positive regard, and the role of an “expert”. Research has shown that clients are more likely to perceive strong rapport when clinicians demonstrate qualities such as empathy, warmth, and active listening (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2003). In turn, positive perceptions of rapport have been found to predict better treatment outcomes, including greater client engagement, reduced dropout, and improved symptom reduction across various forms of therapy (Flückiger et al., 2018; Horvath et al., 2011).

Listening skills are another key component of the clinical interview. It is crucial for the clinician to be actively listening to the client as opposed to just passively taking in the information. Active listening can result in clients feeling more understood (Weger et al., 2014), as the clinician is not just hearing but really attempting to understand what they have said. Table 1 describes several active listening skills that are fundamental for a successful clinical interview.

| Non-Directive Listening Response | Description | Primary Intent/Effect |

| Attending behaviour | Eye contact, leaning forward, head nods, facial expressions, etc. | Facilitates or inhibits spontaneous client talk. |

| Silence | Absence of verbal activity. | Places pressure on clients to talk. Allows “cooling off” time. Allows the clinician to consider the next response. |

| Paraphrase | Reflection or rephrasing of the content of what the client said. | Assures clients you hear them accurately and allows them to hear what they say or correct you if you misunderstood. |

| Clarification | Attempted restating of a client’s message, preceded or followed by a closed question. (e.g., Do I have that right?). | Clarified unclear client statements and verified the accuracy of what the clinician heard. |

| Reflection of feeling | Restatement or rephrasing of clearly stated emotion. | Enhances clients’ experiences of empathy and encourages their further emotional expression. |

| Summarization | Brief review of several topics covered during a session. | Enhances recall of session content and tied together or integrates themes covered in a session. |

Non-verbal cues are equally important during a clinical interview, and it is crucial for the clinician to attend to these. There may be important discrepancies between what a person is saying and how they are behaving (e.g, client says they’re fine but cannot make eye contact). This clinician can also utilize these non-verbal cues to communicate that they are listening (e.g, head nodding, eye contact).

Test yourself!

Clinical interviews typically rely on a variety of question types to gather comprehensive and accurate information while building rapport with the client. Several question styles are outlined in Table 2, although the exact nature of questions will depend on the type of clinical interview conducted (e.g., structured vs unstructured). Each type plays a distinct role in shaping an effective and ethically sound clinical interview.

| Type | Importance | Example |

| Open-ended | Gives the client responsibility and latitude for responding. | “Would you mind telling me about your experiences in the army” |

| Facilitative/Clarifying | Encourages the flow of conversation and clarity. | “Can you tell me a little bit more about that” |

| Confronting | Challenges inconsistencies. | “Before, you said you felt depressed all day long, but now you’re saying that you go out with your friends every night. Can you help me understand?” |

| Direct | Challenges appropriately once rapport has been established. | “What did you say to your father when he criticized your choice?” |

Lastly, effective documentation and note-taking are essential for summarizing the information gathered during the interview. Psychologists must document key details quickly and concisely to accurately recall and document information after the interview. While note-taking is important, it is equally critical to remain present during the interview and minimizing distractions to the client. Documentation must also adhere to ethical and legal standards, maintaining confidentiality and safeguarding sensitive information. These records may be subpoenaed in legal proceedings to assess a client’s mental health status, determine risk levels, or evaluate the quality of care provided.

Test yourself!

Types of Clinical Interviews

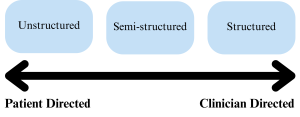

There are three main types of clinical interviews: structured, semi-structured, and unstructured. Each type has its own unique characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages, which are crucial for clinicians to understand in order to select the most appropriate approach.

Structured Clinical Interviews

Structured clinical interviews involve a predetermined set of standardized questions that the clinician asks. The most standardized to administer is the structured interview. These are highly guided interviews, offering little flexibility to the interviewer (Houtkoop-Steenstra, 2000; Mueller & Segal, 2015; Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2014). One example of a structured interview is the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), which is designed to quickly assess major psychiatric disorders according to DSM-5-TR or ICD criteria.

The primary strength of structured interviews lies in their high reliability and diagnostic consistency, making them especially valuable in research and large-scale clinical trials or other research contexts. They reduce interviewer bias and ensure that all relevant diagnostic criteria are systematically addressed. Because the questions are standardized, they minimize the influence of the clinician’s personal biases and ensure that the client is assessed objectively. However, the rigidity of structured interviews can also be a drawback. The lack of flexibility may hinder the development of rapport between the clinician and the client, as it can feel less personal. Additionally, the structured format may not allow for the exploration of client concerns that fall outside the predetermined questions.

Semi-Structured Clinical Interviews

Semi-structured clinical interviews are a compromise between structured interviews and unstructured interviews. They include a core set of standardized questions while still allowing the clinician freedom to ask follow-up questions based on the client’s responses. This format enables clinicians to gather essential diagnostic information while also exploring ideas the client presents as they deem accordingly (Mueller & Segal, 2015; Pashak & Heron, 2022).

The most common clinical interview in North America is the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5; APA). It is considered the gold standard for diagnosing psychiatric disorders based on DSM-5 criteria. Indeed, research using the SCID-5 demonstrated excellent reliability among various mood, anxiety, psychosis, and substance use disorders (Osorio et al., 2019), highlighting its use in clinical practice. Multiple versions have been developed, including a version for research, clinical and personality. The most comprehensive version is the Research Version, covering most of the DSM-5 diagnoses. The Clinical Version is shorter, designed for more routine clinical use, while the Personality Version is designed to evaluate all 10 DSM-5 personality disorders. Another example of a semi-structured interview is the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS), adapted to suit children with parental input. Importantly, both the SCID-5 and K-SADS require specialized training or certification to administer effectively. While these tools provide a structured framework, they still rely on the clinician’s judgment, experience, and interpretive skill to probe responses, clarify ambiguities, and make accurate diagnostic decisions. This balance between structure and clinical expertise is what makes these interviews both powerful and complex tools in psychological assessment.

Unstructured Clinical Interviews

Unstructured clinical interviews are characterized by their open-ended nature, allowing clinicians to ask any questions that come to mind in any order. This format fosters a more conversational atmosphere, which can help build rapport and make clients feel more comfortable sharing sensitive information. The flexibility of unstructured interviews can lead to information that may not emerge in more structured formats with specific questions and follow up questions.

While useful, unstructured interviews present challenges in terms of reliability and validity. The variability of information gathered makes it difficult to compare findings across different clients or to compare to diagnostic criteria. The lack of structure may prevent the clinician from gathering all of the essential information to complete a useful and accurate assessment (Mueller & Segal, 2015). Additionally, the risk of interviewer bias is heightened when using unstructured interviewing (Aklin & Turner, 2006). The clinician’s personal beliefs and experiences may shape the direction of the conversation. For example, a clinician may over-focus on a 2SLGBTQIA+ client’s sexual orientation or gender identity as the source of their issues and forget to address other important areas like career or relationships.

Despite their lower diagnostic reliability, unstructured interviews are the most commonly used format among practicing clinicians (Meyer et al., 2001), likely due to their ease of use and ability to adapt to individual clients. However, research strongly recommends that interviews, whether structured or unstructured, be used in combination with other assessment methods (e.g., standardized questionnaires, behavioural observations) to increase diagnostic accuracy (Meyer et al., 2001).

Test yourself!

Special Considerations in Clinical Interviewing

Cultural Awareness and Humility

Clinical psychologists work with people from diverse backgrounds, each with their own unique needs and experiences. A psychologist must consider how individuals think, feel, and behave while considering how different racial, ethnic, linguistic, and religious backgrounds may influence world views. Cultural diversity brings nuances that require sensitivity to ethnic, socioeconomic, regional and spiritual variables. This means clinicians must strive to remain mindful of their own biases and world views and consider those of their clients when working with them.

Bias is inherent in all people and is a significant challenge impacting all psychologists. Surface-level responses, such as first impressions or emotional reactions, can easily influence clinicians (and clients). Bias refers to typically subconscious, systematic tendencies to think, feel or judge in ways that are not rational and are often learned through personal experiences, which develop heuristics or “cognitive shortcuts” (Gilovich et al., 2019; Yager et al., 2021). This means that we may assume somebody with face tattoos is less trustworthy or assume somebody of Asian descent is more intelligent. Obviously, these factors are unrelated, but it is possible that media depictions of individuals or what we were taught from relatives while growing up could lead us to hold these subconscious beliefs about a person’s character, which might further lead us to make entirely unfounded assumptions. Research has shown that clinician bias disproportionately affects marginalized groups, leading to misdiagnoses (Sayegh et al., 2023). Implicit racial biases have been linked to differential diagnoses, treatment recommendations, and perceptions of client credibility (Snowden, 2003). These challenges are most pronounced when working with unfamiliar groups whose cultures differ greatly from the clinician’s (Snowden, 2003). This might lead a clinician to assume that somebody showing little emotion is demonstrating resilience or that misreading culture-specific expressions represents atypical behaviour. Psychologists need to recognize their own biases and understand how they can impact clinical judgment.

Microaggressions, which are unintended, subtle, direct or indirect insults resulting from a cultural bias, are incredibly damaging to the therapeutic relationship (Owen et al., 2014). When a client speaks to a psychologist, they are creating a bond together, which requires trust to create a working alliance between all parties involved. However, if the client feels as though they are being attacked or disadvantaged by an implicit negative perception from the clinician, it becomes significantly harder to build the trust needed for practical assessments and interventions; a client may be less honest or open and they might not return for more sessions (Owen et al., 2014).

For example, a clinician might ask a bilingual client, “But what language do you really think in?”, implying their identity is fragmented. Alternatively, they might compliment an Indigenous client by saying, “You are so articulate,” suggesting surprise or a stereotype about intelligence. Asking a client of colour, “Where are you actually from?” can make the person feel alienated or othered. Biased comments like these can quickly erode the therapeutic relationship, hindering accurate assessment. To avoid this, keep in mind an individual’s culture, socioeconomic standing, religion, gender, sexual orientation and ability or disability. Avoid assumptions based on stereotypes or using overgeneralizations. Research has shown that demonstrating cultural humility and a greater competence in multicultural practice significantly strengthens the therapeutic alliance (Constantine, 2007).

While no one can be fully aware of all cultural diversity, it is your responsibility to be mindful of your cultural blind spots. If possible, be upfront and transparent about any uncertainties. If a microaggression occurs, whether intentional or not, acknowledge it and attempt to address it. Clinicians should also try adapting interviewing and assessment techniques rather than forcing clients to adjust. Invite feedback from others to improve your cultural responsiveness. Depending on the context and the relationship, this may even include input from your clients. Always work to educate yourself and reflect on the intent and impact of your actions; even the most well-intended comments can still cause harm. Addressing microaggressions requires ongoing self-awareness and continuously learning about and respecting diverse cultural perspectives, which is critical for developing cultural humility (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2014).

Behavioural Observation

When we speak about interviewing, we often focus on the verbal aspect of the words people use when asking and responding to questions. However, a lot can be learned if we not only pay attention to a client’s responses but also to their behaviour. Thus, it is the clinician’s task to not only interpret the content of the client’s verbal response but also carefully observe their behaviour. While clients are responding to questions, an interviewer should observe the way the clients are presenting themselves (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2014). Things such as attention span and focus, erratic behaviour, or impulsive responses can all give valuable insights into a client’s current thoughts, emotions, or underlying conditions.

For example, suppose Alex, an eight-year-old child, is brought in for an assessment because their teacher reported concerns about their ability to focus in the classroom. During the interview, Alex appeared engaged and responded to questions appropriately. However, the clinician noticed that they frequently shift in their seat, struggle to maintain eye contact and fidget with objects on the table, occasionally, blurting out answers before the clinician finishes speaking. In Alex’s case, this may reveal underlying anxiety, hyperactivity, or difficulty with self-regulation, and these factors should be explored with further testing or interviewing.

Aside from behaviour, a client’s appearance can serve as a subtle yet important indicator during assessments. Observing how a person presents themselves may provide clues into how their mental health may be impacting their daily life (Ghassemi et al., 2023; Stewart et al., 2022; Ward & Scott, 2018). When looking at physical appearance, factors such as clothing, hygiene, and overall attentiveness to physical presentation may all be relevant factors. Suppose a client arrives in sleepwear and appears to have not showered in days. In that case, it may indicate a loss of motivation towards self-care and signal depressive symptoms or other difficulties managing daily responsibilities, such as those resulting from a disorder. They could be presenting an inability to self-care, which can worsen mental health symptoms (Mu et al., 2022). Although it is important to observe and take note of a person’s presentation, clinicians must approach this aspect with sensitivity and professionalism. This means avoiding making assumptions based on superficial traits. These observations should serve as clues to solve a larger puzzle and only comment on aspects of the presentation that are appropriate to the case.

Personal presentation and behavioural observations should be used together to help guide the assessment, but should never be the primary evidence for a diagnosis (Haynes, 2001). They are subjective and should be treated as possible symptoms because they can be interpreted differently depending on the situation or demographic (Ghassemi et al., 2023). When put together, a client with a disorganized appearance exhibiting poor focus and low signs of energy might support a depressive disorder, whereas the same person acting restless or hyperactive might suggest an entirely different clinical picture. By integrating observations about personal presentation and behaviour, clinicians can gain valuable insight into a client’s overall functioning.

Naturalistic Observation

It should be noted that people’s behaviours may alter in a clinical setting for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a guardian or teacher may report that a child is having issues focusing in school, but there are no signs of such issues during an assessment interview (De Los Reyes, 2011). In cases like this, the child may not present any of the reported symptoms because the interview is a new environment which has grabbed their attention and is highly stimulating, leading to an inconsistency in evidence (De Los Reyes, 2011). It is also impossible to assess the child through typical interviewing techniques because they may not be able to self-reflect or adequately understand the nature of the questions effectively (Young et al., 2010).

This is precisely the case with Alex. Although their teacher reported that they struggle to sit still and listen during class, during the clinical interview, Alex remained seated and attentive for most of the session. In a case like this, extending the assessment beyond the clinical environment and using a data-gathering technique called naturalistic observation may be appropriate. This technique allows clinicians to witness real-world behaviour. It can often reveal aspects of a client’s behaviour that they may be unaware of, unwilling to disclose, or unable to articulate.

There are many challenges with naturalistic observation, the most obvious of which is the need to leave the clinical setting and meet a client where they are located; this can be extremely time-consuming, and coordinating a time at which symptoms are most likely to occur can be even more challenging. Furthermore, a clinician must obtain permission from all parties who may be present when the observation is ongoing. This may be straightforward when observing a child at their own house, and consent is only required from caregivers. However, if you need to go to a classroom or other group setting, it could become more challenging to get permission from all third parties who may be present, such as teachers and school administrators. Considering these challenges, the largest by far is the clinician’s need to blend into the background and not influence the environment. People’s behaviour may change when they are aware they are being observed, known as observer bias (Bauer et al., 2025; Cañigueral & Hamilton, 2019). So, when the goal is to watch a client in their natural environment, the clinician wants to melt into the background or become a so-called “fly on the wall” to ensure having as little influence as possible.

While naturalistic observation provides invaluable insights, it still should not be used alone when creating an assessment, as it only provides a picture of the symptoms of a challenge the client faces, not the cognitive process or personal experiences leading to them. While the standard clinical interview is typically the first step in the assessment process and serves as the bedrock for building rapport and understanding presenting concerns, a good assessment will draw on as many sources as possible (American Psychological Association, 2020; Groth-Marant, 2003).

Referring back to Alex, after conducting naturalistic observation in a classroom, it is revealed that they often leave their seat, struggle to focus on tasks, and interrupt classmates. While these behaviours alone could suggest an attention deficit disorder, they do not provide a complete picture. These symptoms might also arise from anxiety, a learning disability or a sensory issue, and further testing should occur in order to try to explain the observed symptoms and understand the root of Alex’s symptoms.

Self-Monitoring

In a perfect world, we could monitor a client all day to help create a complete picture of their life and symptoms, but that is not really possible, so instead, we use self-monitoring (Haynes et al., 2019). This strategy empowers the client to reflect and report on their own experiences by asking them to maintain a detailed record of their day-to-day experiences (Haynes et al., 2019). Although sometimes having a client come in once a week to recount their experiences from memory is sufficient, memories fade and become distorted over time, so specific techniques may be employed to help the client keep track of their behaviour (Haynes, 2000; Haynes et al., 2019). This will often be given to them as homework. Clients are asked to maintain a daily record of their experiences when self-monitoring and are typically directed to reflect on behaviours, emotions, thoughts or physical symptoms (Haynes et al., 2019). This might include habits like procrastination, mood fluctuations, negative thoughts, or physical signs such as an increased heart rate or tension. Self-assessment provides valuable insight into a client’s daily life and a glimpse into their cognitive functions that observations struggle to capture (Kazdin, 1974). Empowering clients to monitor their behaviours helps clinicians gather detailed data about the symptoms’ frequency, intensity, and context. This can provide unique information when developing tailored interventions by identifying patterns and triggers that a client may be unable to identify themselves. There is even the potential to use self-monitoring to effect change in a client’s behaviour and utilize it as a part of a treatment plan, since, if used correctly, it could help the client gain awareness or insight into their negative behaviours (Hayes & Cavior, 1977; Kazdin, 1974; Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999). However, while self-assessment can be a powerful tool, it has its challenges.

The most significant limitation of self-monitoring is its lack of reliability (Dang et al., 2020). Unfortunately, humans are imperfect, and clients make mistakes like all humans. This means that clients may make errors when they record incidents or in what they record; they may even disregard a vital incident altogether. This could be because they simply do not properly understand the nature of the self-monitoring they have been asked to do, or they are ashamed to document a thought they find undesirable or embarrassing. For example, a client may log vague emotions, not understand the importance of being specific, or they may be embarrassed to admit that they engaged in substance use. This skews the data in a way that either lessens the severity of a symptom or could lead a clinician to explore other paths and create ineffective interventions.

Psychologists can work to lessen these issues and improve reliability by providing clients with clear guidelines and choosing careful wording with rationale tailored to their symptoms and behaviours (Morsbach & Prinz, 2006; Schwarz, 1999). In this context, behaviour refers to any observable and measurable actions or responses, such as avoidance of social situations, increased heart rate, fidgeting, or verbal expressions of distress, that are relevant to the client’s presenting concerns. For example, a client concerned with anxiety may be asked to record the intensity, duration, and triggers of an anxious episode on a simple scale or checklist. Providing a template or example for clients ensures clarity and helps them know exactly what to observe and document.

In addition, clinicians can use mobile apps with diaries or symptom-tracking features to simplify the process and make it more convenient for clients (Arrow et al., 2023; Chan et al., 2021). Apps such as daily mood trackers or cognitive behavioural diary apps might enable the clinician to schedule reminders through notifications to the client, reminding them to record data at specific times. An app might also provide a sleek and visually appealing way to input data, including giving menus for tracking symptoms or providing visualized graphs over time. These tools are intended to reduce the cognitive load on the client and ensure consistency throughout data collection, making interpretation more manageable for the clinician.

Finally, when collecting data through self-monitoring, the mere act of monitoring oneself can alter behaviour (Nelson & Hayes, 1981). Unfortunately, just as with all other observation methods, if the client is aware of the observation, their behaviour might change. In the case of self-observation, a client may become more self-aware or “self-conscious” of their actions and might think them through more carefully or consider the impact (Alexis Bridley et al., 2020). This might lead to them making fewer impulsive decisions than they would have otherwise or suppressing certain habits. This phenomenon, known as reactivity, impacts all forms of observation and is something clinicians need to be cognizant of when considering data gathered from observation, as it can obscure natural behaviour patterns. As such, given the risk reactivity poses, observation methods should never be the sole source of evidence in an assessment. They are best viewed as one valuable tool among many within a comprehensive clinical assessment (Bornstein, 2017; Meyer et al., 2001).

Conclusion

In conclusion, clinical interviewing and behavioural observation are foundational methods in clinical psychological assessment, offering complementary insights into a client’s mental health and functioning. Interviews (ranging from unstructured to highly structured formats) allow clinicians to gather detailed personal narratives and diagnostic information, and behavioural observation provides a real-time, objective lens into how individuals act and respond in various contexts. Together, these tools require not only technical skill and theoretical knowledge but also ethical sensitivity, cultural competence, and clinical judgment.

Test yourself!

Media Attributions

- psychologist at work

- Empathy Warmth Listening © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- types of interviews © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Behavioural observations © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- My daughter © MIKI Yoshihito is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

A structured conversation between a psychologist and a client used to gather information, build rapport, and guide assessment or treatment planning.

A method in psychology where a clinician systematically watches and records a person’s actions, expressions, or interactions to understand their behaviour in natural or clinical settings.

A relationship is developed between the client and clinician, which helps create a safe environment for clients to share their thoughts and feelings openly.

The ethical and legal obligation of psychologists is to protect clients' private information and only disclose it with informed consent or under specific circumstances required by law.

Situations in which a psychologist is obligated to break confidentiality and disclose patient information to another person or agency.

A situation where a psychologist faces a conflict between two or more ethical principles, making it challenging to determine the right course of action without potentially violating one of those principles.

The process of sharing information with patients that is essential to their ability to make rational choices among multiple options (Beahrs & Gutheil, 2001)

The collaborative and trusting relationship between a therapist and client.

The practice of fully focusing on, understanding, and thoughtfully responding to what someone is saying, while showing genuine interest through both verbal and nonverbal cues.

A type of interview in which the interviewer asks a standardized set of predetermined questions in a specific order to ensure consistency and reliability across participants.

Interviews that follow a general framework of predetermined questions while allowing flexibility for the interviewer to explore topics in more depth based on the participant’s responses.

Flexible, open-ended conversations without a fixed set of questions, allowing the interviewer to explore topics freely based on the flow of the discussion and the participant’s responses.

A standardized diagnostic tool used by trained clinicians to systematically assess and diagnose major mental disorders based on the criteria outlined in the DSM-5.

Subconscious, systematic tendencies to think, feel or judge in ways that are not rational and are often learned through personal experiences, which develop heuristics or “cognitive shortcuts”.

Unintended, subtle, direct or indirect insults resulting from a cultural bias.

An ongoing process of self-reflection and learning in which individuals recognize and address their own cultural biases, remain open to others’ cultural identities and experiences, and approach each interaction with respect, curiosity, and a willingness to learn.

A type of systematic error that occurs when a researcher's or clinician’s expectations, beliefs, or personal experiences influence their observations or interpretation of a subject’s behaviour or responses.

The process by which individuals observe, track, and record their own thoughts, emotions, or behaviors.

The phenomenon in which a person’s behavior changes because they are aware they are being observed or assessed.