1 What is Clinical Psychology?

Dr. Laura Lambe and Dr. Angela Weaver

Mental health is a growing profession in Canada and around the world. Thanks to initiatives like Bell Let’s Talk and other national advocacy campaigns, our population is increasingly aware of mental health symptoms and how to access treatment. Let’s imagine you’ve been feeling depressed lately, unable to participate in activities you previously enjoyed, and have experienced a lot of trouble sleeping. You decide you want to talk to a mental health professional about your experiences. But who do you contact? Your family doctor? A nurse? A psychiatrist? A social worker? A counsellor? Or maybe a clinical psychologist? This chapter will provide a general overview of clinical psychology as a profession to help you answer this question.

- Understand the origins of clinical psychology.

- Understand the training required to become a clinical psychologist.

- Understand the varied settings and roles of clinical psychologists.

- Learn about other mental health professions and their role in a multidisciplinary health team.

What is clinical psychology?

Clinical psychology is defined by the Canadian Psychological Association as “a field of practice that deals with human functioning; either human problems and their solution, as well as with the promotion of physical, mental, and social well-being” (Canadian Psychological Association, 2018). At its core, the goal of clinical psychology is to reduce the distress associated with mental health conditions.

Clinical psychology is a relatively new field of study and practice, emerging as a profession after World War II (Gee et al., 2022). During this time, the United States (and Canada) anticipated a looming demand for clinical services for veterans. A conference in Boulder, Colorado (Hilgard et al., 1947) approved a scientist-practitioner model to train more PhD-level clinical psychologists, meaning that both research and applied clinical skills are foundational to the profession. The Ph.D. training model is sometimes referred to as the “Boulder model” and continues to represent the most common training model in Canada today.

While this training model might seem like overkill (yes, it is like doing PhD-level research at the same time as balancing clinical training and seeing clients), it served to establish the legitimacy as clinical psychology as an evidence-based science. Proponents of this training model argued that “…the future of clinical psychology hinges on our ability to integrate science and practice”, and that ultimately, there is no choice between science or practice (McFall, 1991). In 1991, Richard McFall published this argument in an article known as “McFall’s Manifesto” that argued that scientific clinical psychology is the only acceptable form of clinical psychology. In other words, the scientific training model is necessary for producing clinicians that employ evidence-based interventions. Relatedly, he argued that psychological services should not be administered to the public unless the benefits are first scientifically validated. Consistent with this model, current Canadian clinical psychology graduate students tend to report that their graduate training is slightly more weighted toward research than clinical practice (Peluso et al., 2010).

Critics of the Boulder model argue that it places too much emphasis on research rigour, skills that many practicing clinical psychologists never use in their daily practice (Gee et al., 2022). These criticisms, paired with an ever-increasing demand for a mental health care workforce, have led to the creation of a practitioner-scholar training model, in which clinical psychologists earn a Doctor of Psychology (Psy.D.) degree. The first Psy.D. program was established in 1973 in the United States (Peterson, 1992), with Canadian programs only recently taking off in the mid-2000s.

There are approximately 30 Canadian universities that are accredited by the Canadian Psychological Association with doctoral training programs (Ph.D. or Psy.D.) in clinical psychology, essentially creating a national standard of training with clinical psychology (Dobson, 2016). While there are some Master’s-level programs in Canada (and some provinces that licence Master’s-level psychologists), the CPA does not accredit Master’s-level training programs. As noted by Dobson (2016), the accreditation of clinical psychology programs in Canada, beginning in 1994, has served to enhance the quality of these programs and the calibre of students who are trained. Indeed, within these programs, becoming a clinical psychologist usually takes 6-7 years. Gaining admittance to a Ph.D. or Psy.D. program in Canada is remarkably competitive, as most programs receive >100 applications for 5-8 spots in a given program (for more information be sure to review a given program’s public disclosure table, such as this one from Dalhousie University).

After earning a PhD or a PsyD, potential clinical psychologists cannot call themselves psychologists until they are licensed as health professionals. In Canada, healthcare falls under provincial jurisdiction, meaning that each province/territory has its own licensing body and their own rules for regulating the profession. To be a registered psychologist, psychologists must meet the standards of the profession as described by the provincial licencing body. In most cases, these standards include an advanced degree (e.g., Ph.D. or Psy.D.), at least one year of supervised practice, and having passed standardized oral and written exams on psychology and ethics of the profession. Ultimately, the purpose of such standards and the licensing body is to protect the public, as clients who believe they have received unethical or incompetent care from a psychologist can lodge a complaint with the regulatory organization.

For example, in Nova Scotia, Psychology is regulated under the Nova Scotia Psychologists Act (2000) and psychologists are registered with the Nova Scotia Board of Examiner’s in Psychology (NSBEP). The Psychology Act (2000) is a law protecting the term “psychologist” and “psychological services”, meaning that only those who have earned the proper credentials and are licensed with NSBEP can call themselves “psychologists” and provide such care. Professors in psychology are not required to be licensed by NSBEP but must clearly identify themselves as “professors of psychology” and not psychologists. Similar laws exist in other provinces, such as The College of Psychologists Act (2017) in New Brunswick and the Psychologists Act (2009) in PEI.

Related terms, like “therapist” or “counsellor” are not licensed terms, meaning that anyone (with any training or no training at all) can use those terms. If you receive services from an unregulated provider, there is no regulatory organization with whom to lodge a complaint, and there are no standards for providing care. To make it especially confusing, however, “Registered Counselling Therapist” IS a licenced profession (see more below). This is why it is always important to ask questions about the training and background of your mental health care provider!

Clinical psychologists must also follow the Code of Ethics established by their provincial regulatory body. The Code of Ethics consists of guidelines for protecting the well-being of individuals, the public, and society. For example, the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (4th edition) articulates the ethical principals, values, and standards to guide all members of the Canadian Psychological Association. The ethical guidelines outlined in the Canadian Code of Ethics are structured into four pillars:

- Respect for the Dignity of Persons and Peoples: Emphasizes the inherent worth of people, non-discrimination, moral rights, informed consent, and privacy.

- Responsible Caring: Emphasizes competence, maximizing benefits and minimizing harms, and only providing care that respects the dignity of others.

- Integrity in Relationships: Emphasizes accuracy, objectivity, straightforwardness, and avoidance of conflict of interest in relationships.

- Responsibility to Society: Emphasizes the development of knowledge and undertaking activities that respect and benefit society.

The Canadian Code of Ethics also provides guidance for psychologists on ethical decision-making. While all four pillars should be taken into account when engaging in ethical decision making, the four pillars are ordered according to the weight each generally should be given when conflict arises.

For example, you might imagine a scenario where a psychologist is providing care to a teenager, who does not want to involve their parent in their treatment. The psychologist, however, receives a demanding voicemail from the parent wanting to know about their child’s treatment since they are the one paying the bill. In this situation the psychologist has a duty to maintain the teenager’s privacy and confidentiality, as these principles fall under the first principle of Respect for the Dignity of Persons and Peoples.

What do clinical psychologists do?

Clinical psychologists have advanced training in assessing and treating a variety of mental health difficulties and neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, learning disabilities), as well as difficulties associated with personal health problems, relationship difficulties, and other life stressors. Clinical psychologists may work with children, adolescents, adults, families, couples, groups or organizations. The scope of their work may be general mental health or focus in a particular specialty area within the umbrella of clinical psychology, such as health psychology, clinical neuropsychology, or clinical forensic psychology. Regardless of where they work or their training background, Canadian clinical psychologists must have core competencies in interpersonal relationships, assessment and evaluation, intervention and consultation, research, and ethics and professional standards (CPA Mutual Recognition Agreement, 2001).

As described in the table below, the scope of practice for clinical psychologists encompasses many different areas:

| Assessment and diagnosis | Psychological assessments are used to understand and inform recommendations for an individual, couple, or group. Clinical psychologists have advanced training in administering and interpreting psychological assessment measures, such as IQ tests. They also have advanced training in clinical interviewing and case conceptualization, enabling them to take a comprehensive view of a person’s mental health across biological, social, and psychological domains. Psychologists can communicate a diagnosis, typically as outlined in the DSM-5-TR, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. |

| Intervention | Psychological interventions, commonly referred to as “therapy”, involve the treatment of psychological disorders. Clinical psychologists use a range of intervention approaches when working with clients, including such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), and dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT). Psychological interventions have strong research support for a variety of mental health conditions (Canadian Psychological Association, 2022) and are a recommended first-line treatment for mood and anxiety disorders by the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2023). Given their advanced research training, clinical psychologists typically employ interventions that are empirically supported. |

| Prevention | Clinical psychologists may be involved in the development, delivery, and evaluation of programs that aim to prevent psychological disorders before they develop, or to reduce risk factors for psychological disorders (e.g., a bullying prevention program). Clinical psychologists bring unique skills in research and program evaluation, helping to determine if such prevention programs have desired impacts. |

| Research | Clinical psychologists actively contribute to empirical research during their PhD training, and many continue to conduct research throughout their careers. At its core, clinical psychology is a science. This research emphasis ensures that psychological assessment, intervention, and prevention efforts are evidenced-based. |

| Consultation, supervision, and teaching | Many clinical psychologists consult with schools, other healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians), the legal system, and community agencies as part of their work. They may also supervise other practitioners or clinical psychology trainees within a multidisciplinary team. Lastly, some clinical psychologists teach courses on psychopathology, assessment, and intervention within university programs. |

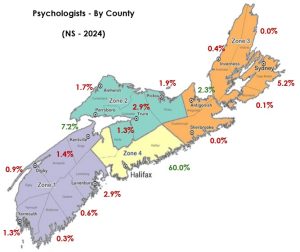

Canada has approximately 21,000 psychologists, with approximately 1424 psychologists in Atlantic Canada (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2024). However, not all of these are clinical psychologists, and some may be registered with other specialties such as school psychologists. For example, in Nova Scotia there are 696 psychologists, with 464 (67%) primarily registered as clinical psychologists. Across the country, there tends to be an over-representation of clinical psychologists in urban centres, with very few clinical psychologists practicing in rural areas. For example, 60% of all psychologists registered in Nova Scotia work in Halifax county, which accounts for 48% of the population. This discrepancy highlights a growing need for clinical psychologists across Canada, particularly in rural and underserved communities. You can learn more about the need for evidence-based mental health care in rural communities in this article.

In 2013, Hunsley et al. surveyed over 500 psychologists from across Canada to better understand their practice characteristics. Approximately three-quarters of their respondents identified as women, representing a dramatic shift from the early 1990s when 70-80% of psychologists were men (Hunsley & Lefebvre, 1990; Warner, 1991).

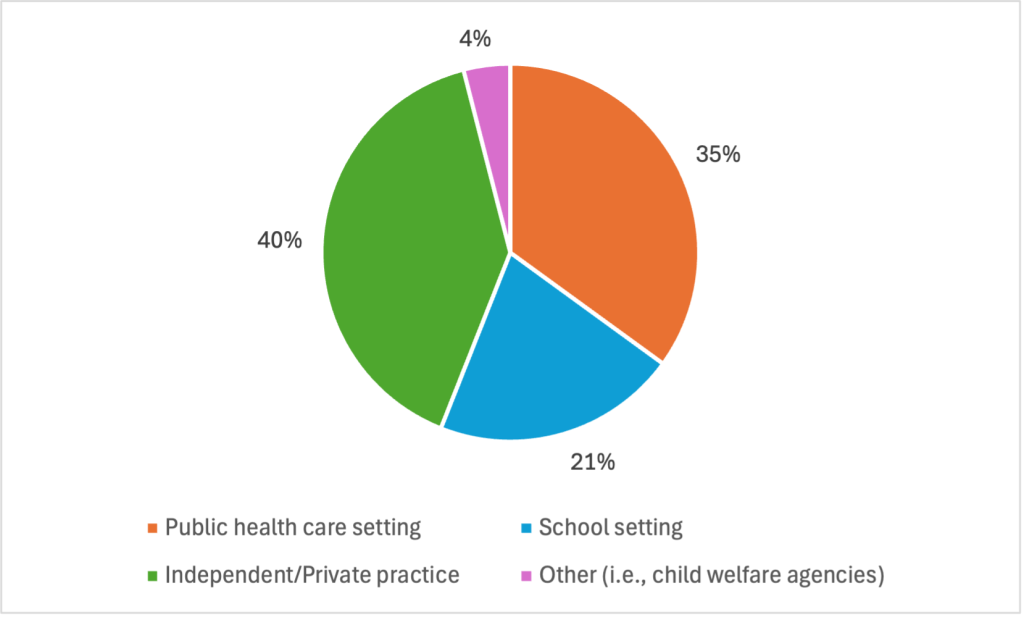

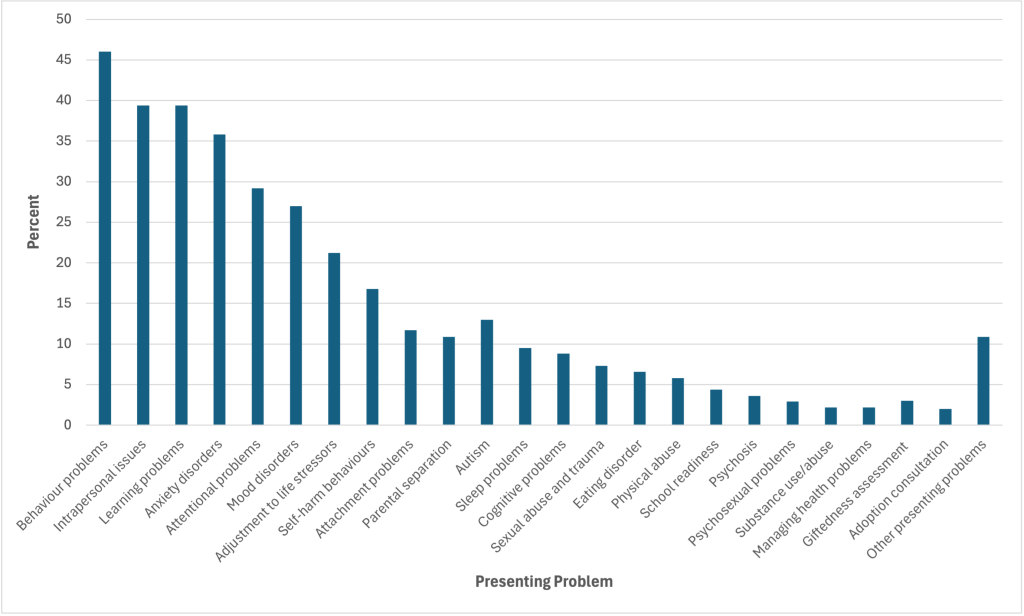

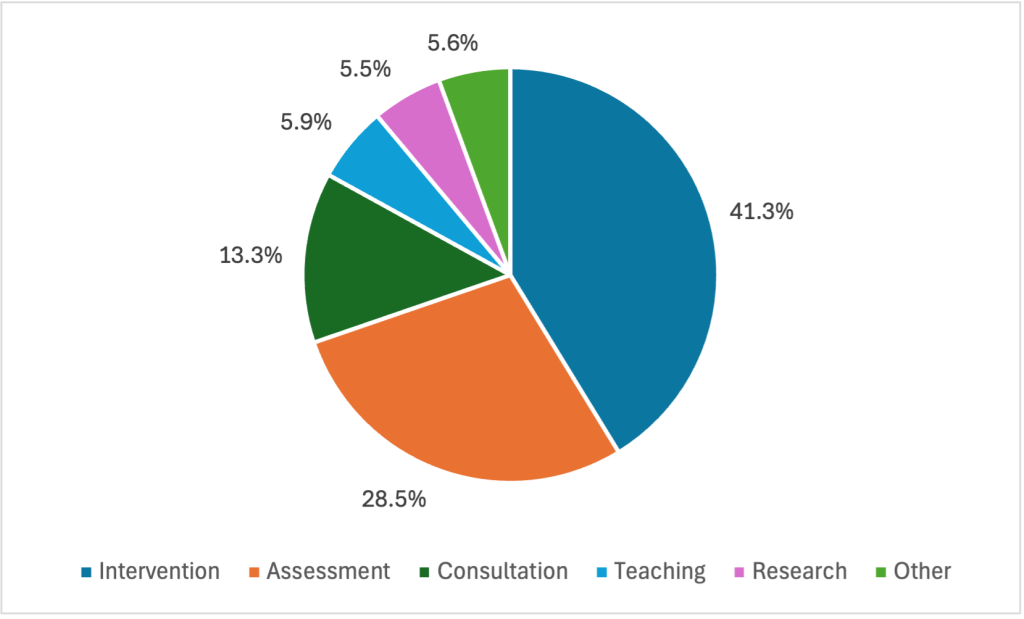

As shown in the graphs below, Canadian psychologists commonly work in both public and private sectors, and work with a variety of mental health concerns, the most common being anxiety and mood disorders. Unsurprisingly, clinical psychologists tend to spend most of their time in working directly with clients in intervention and assessment roles, with a smaller proportion of time spent in other activities. The vast majority (80%) of Canadian psychologists approach their work using a cognitive-behavioural theoretical orientation (Hunsley et al., 2013).

What about Bob? How therapy is portrayed onscreen.

The average person probably doesn’t know a lot about what therapy is or what different types of therapists do. So, how does the average person form their idea of therapy? For better or worse, media portrayals likely help to form their “therapy schema”. The media has the power to demystify the process, create awareness, and improve mental health literacy. So, what’s the problem? Unfortunately, many media depictions are inaccurate and problematic portrayals of therapy.

Some depictions of therapists portray them as mind-reading miracle workers who immediately know what is wrong with someone and can provide an “instant cure”. Other depictions position therapists as villains, exploiting their patients for fame (e.g., Dr. Fletcher, Split, 2016), in order to test out highly experimental treatments (Dr. Cawley, Shutter Island, 2010), or to gratify their own sadistic tendencies (Dr. Becker, The Jacket, 2005).

One of the most problematic onscreen tropes involves boundary violations. The Canadian Code of Ethics guides psychologists to avoid “dual relationships” and maintain professional boundaries. This is very important to protect our clients, who can be very vulnerable. Yet, movies and series often show therapists engaging in activities with clients that could be viewed as blurring boundaries and violating ethical standards. In Silver Linings Playbook (2012), Dr. Patel, a psychiatrist who is treating the main character, Pat (played by Bradley Cooper), for bipolar disorder, attends a baseball game with Pat and his family. In What about Bob? (1991) a psychiatrist portrayed by Richard Dreyfuss ends up having his patient, Bob, (played by Bill Murray) stay with him and his family during vacation.

Much more problematic are films depicting a therapist having a sexual or romantic relationship with their client. In the film Numb (2007), Matthew Perry portrays a character in treatment for depression and depersonalization/derealization disorder. He begins having a sexual relationship with his therapist, Dr. Blaine, played by Mary Steenbergen. In the British comedy series, The IT Crowd, character Moss’ psychiatrist cuts off therapy with him because she wants to initiate an affair. While these kinds of ethical violations do unfortunately happen in real life, these shows/films tend to treat them lightly for comedic purposes, which fails to convey how harmful this can be to vulnerable clients.

For a fascinating review of mental illness in film, check out Movies and Mental Illness: Using Films to Understand Psychopathology by Wedding & Niemiec.

Clinical psychology versus related mental health professions

The scope of practice for a clinical psychologist overlaps (somewhat) with a variety of other regulated mental health professionals. For example, providing “therapy” is not unique to clinical psychology and is something that all mental health care professionals may engage in:

Psychiatrists (MD). Psychiatrists are medical doctors (MD), meaning that they have completed medical school plus advanced residency placements in psychiatry. Like clinical psychologists, psychiatrists can conduct assessments and make diagnoses, provide psychotherapy, consult, supervise, and engage in research and teaching if they wish. Due to their medical background, psychiatrists are uniquely capable of prescribing and managing medication. Thus, in practice, a psychiatrist’s role in a multidisciplinary mental health context often focuses on medication management. They have a particularly critical role in the treatment of more biologically-based mental health disorders, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. There are approximately 260 psychiatrists in Atlantic Canada (9.5 psychiatrists/100,000 population in Atlantic Canada).

Social Workers (B.SW. or M.SW.). Social workers typically have either an undergraduate or master’s degree in social work (B.SW. or M.SW.). Social workers can provide therapy to individuals, families, couples, and groups. While social workers cannot communicate diagnoses, they can still provide therapy for psychological disorders like anxiety and depression. They work in a variety of settings including family courts, hospitals, correctional facilities, human rights organizations, schools, mental health clinics, and in private practice. Social workers bring a social justice lens to mental health care, addressing both individual needs and systemic barriers to well-being. There are approximately 7266 social workers in Atlantic Canada.

Counselling Therapists (M.Ed. or M.A.). Counselling therapists have advanced training in counselling or counselling psychology. In Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, mental health practitioners with this training are regulated as “registered counselling therapists”. In other parts of Canada, these practitioners are regulated with other titles including “registered psychotherapist” (Ontario) and “counselling psychologist” (BC). Since this textbook focuses on the Atlantic provinces, we will use the term “counselling therapist” for simplicity. Typically, counselling therapists provide therapy for adjustment difficulties, relationship problems, grief, or other stressors, but may also see clients with mild symptoms of anxiety, depression, or other mental health disorders. They work in a variety of settings including schools, healthcare settings, and in private practice. There are approximately 1912 counselling therapists in Atlantic Canada.

Occupational Therapists (M.Sc.OT). Occupational therapists have advanced training in assisting people to fully engage in their day-to-day activities (“occupations”), including self-care, school, work, and hobbies. In terms of mental health care, occupational therapists help individuals with mental illnesses learn to adapt and participate more fully in their daily activities. They are especially skilled in identifying and removing barriers (physical, cognitive, environmental) that interfere with an person’s ability to function in everyday life. Some occupational therapists provide therapy, while others work with individuals with mental illnesses to develop routines, enhance communication strategies, or adapt tasks to promote independence and success. They work in a variety of settings including healthcare settings, rehabilitation centres, and in private practice. There are approximately 1465 occupational therapists in Atlantic Canada (approximately 45 occupational therapists/100,000 population in Atlantic Canada).

Think about it:

Imagine you are an inpatient in a psychiatric hospital for a serious mood disorder. After your hospital care, you transition to outpatient services and need help re-engaging with your work and daily activities. How might each of the care providers described above be involved in your care as part of a multidisciplinary care team?

Compare and contrast mental health care providers

The following table provides a summary and comparison of the scope of practice of different mental health care professionals. Clinical psychologists have the most breadth in terms of their scope of practice, which is congruent with the length their training. All of these mental health care professionals play an important role in service delivery.

Table 1. Scope of practice of clinical psychologists, physicians, and other registered mental health care professionals

|

|

Clinical psychologists |

Physicians (e.g., Psychiatrists) |

Counselling therapists, social workers, and occupational therapists |

|

Communicate a diagnosis |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Administer and interpret psychological tests |

Yes |

No* |

No* |

|

Provide psychotherapy |

Yes |

Yes** |

Yes |

|

Prescribing authority |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Program evaluation |

Yes |

No |

No |

Adapted from (Canadian Psychological Association, 2024)

*Can administer and interpret basic screening tests such as a symptom checklist, but not advanced psychological assessments that measure cognition, learning, memory, or personality.

** Data indicates that while physicians and psychiatrists can provide psychotherapy, only 3% of non-psychiatry physicians and 27% of psychiatrists provide this service (Kurdyak et al., 2020).

The (Modern) Origins of Clinical Psychology

Throughout much of history, little was known about assessing, diagnosing, or effectively treating psychological disorders. People held in asylums were often treated poorly, subjected to the whims of the people who ran them, and received little in the way of sympathetic care (particularly if the asylum was underfunded and overcrowded – unfortunately, quite common). Many individuals paved the way for modern assessment and intervention, and/or fought for more humane treatment of people with psychological disorders.

Phillipe Pinel (1745-1826), a French physician sometimes considered “the father of modern psychiatry”, is credited with helping to improve conditions for mental patients, particularly after he became head physician of the Hospice de la Salpêtrière in 1794. While in this role, he fought to have patients unshackled and led to the cessation of “treatments” such as bleeding, purging, and blistering. He also made contributions to early attempts at classification that helped pave the way for our modern diagnostic systems. He argued that treatments should be tailored to the individual, advocating for speaking to the patient regularly and developing a deep understanding of the person and their illness, foreshadowing modern views.

William Tuke (1732-1822) – Tuke, a tradesperson and philanthropist, is credited with pioneering “moral treatment”. After having learned of a community member’s tragic death in an asylum, likely due to maltreatment, and witnessing the horrific conditions at another hospital, Tuke was inspired to raise funds to build a different kind of asylum. The York Retreat, established in 1792, was built on spacious and beautiful grounds. Tuke believed that good food and exercise were important for mental health, and that patients should receive individualized attention and be treated with kindness. Patients were encouraged to enjoy nature on the grounds, socialize, do light manual labour, and take on hobbies. Some components of the treatment approaches at the York Retreat are now viewed by some to be an early form of occupational therapy. Tuke also contributed to legal reforms aimed at changing how asylums were run, such as reducing the use of restraints.

Dorothea Dix (1802-1887) was a retired American schoolteacher who advocated for asylum reform, petitioning the government and raising awareness. As part of an investigation into the treatment of the mentally ill in Massachusetts, she was dismayed to witness the terrible conditions, her report indicating that patients were, “in cages, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience” (Dix, 2006). She began lobbying for better treatment throughout America and the greater commonwealth. She even travelled to Nova Scotia in 1844 and 1849 and spoke to the legislature to argue for better care for the mentally ill. These efforts helped lay the groundwork for the province’s first psychiatric hospital, the Mount Hope Asylum for the Insane (now the Nova Scotia Hospital; Goldman, 1990). Fun fact: while she was in the Maritimes, she even aided a shipwreck on Sable Island!

Although Pinel and Tuke emphasized talking with and developing a deep understanding of, individual patients, the modern origins of psychotherapy (AKA. “Talk Therapy”) owe a great deal to Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). When Freud was studying in Paris under French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893), he observed patients hypnotized by Charcot apparently experiencing great emotional release. He interpreted this as catharsis, a process of emotional release and healing that comes from bringing unconscious material into conscious awareness and processing it, which he believed essential for reducing neuroses. Upon returning to Vienna, Freud experimented with patients talking about their symptoms and difficult memories while under hypnosis and observed improvements, such as in his famous case, referred to as Anna O. (who is credited with coining the term “talking cure”). Freud gradually moved away from hypnosis, observing similar successes by encouraging patients to talk freely, believing that free and uncensored discussion (“free association”) helped clients gain awareness of unconscious material and experience catharsis, which was essential to overcoming psychological problems.

An individual important to modern understanding of the classification of psychological disorders is Emil Kraepelin (1856-1926), a German psychiatrist. Kraepelin emphasized the collection of clinical data and, through careful observation of patients, helped to classify symptoms into manic-depression (now called bipolar I disorder) and dementia praecox (schizophrenia), setting the stage for contemporary classification systems, like the DSM (Decker, 2004). However, we should also note that Kraepelin espoused harmful theories about sexual orientation, and he supported eugenics, so his legacy is problematic.

Alfred Binet (1857 – 1911). The origins of modern cognitive testing are traced to France around the turn of the 20th century. The French government wanted a means of assessing young children entering the school system to identify children who were likely to struggle in regular classroom placements due to learning difficulties. Psychologist Alfred Binet was commissionsed to develop just such a test. Along with colleague Theodore Simon, they developed what came to be known as the Binet-Simon test. Across the pond in America, Lewis Terman (1877 – 1956) standardized the Binet-Simon test for American samples. The Stanford-Binet, as it became known, is still a widely used test of intelligence and now in its 5th edition.

Lightner Witmer (1867 –1956) was an American psychologist who is often credited with founding the field of clinical psychology (and coining the term “clinical psychology”). Witmer was educated in a variety of fields before making waves in psychology, such as studying Art and Finance, and teaching History and English. Witnessing the social problems of the civil war and students struggling with learning issues, inspired him to fight for improved social and educational conditions and made strides in specialized educational supports for students with learning difficulties. He made significant contributions to experimental psychology, educational psychology, and trained other important figures in the field. In 1896, he presented a roadmap to a new discipline to the American Psychological Association, which he called “clinical psychology”. He emphasized a scientific basis, which can be seen in his explanation of the choice of term:

I have borrowed the word “clinical” from medicine, because it is the best term I can find to indicate the character of the method which I deem necessary for this work… The term “clinical” implies a method, and not a locality. When the clinical method in medicine was established on a scientific basis… its development came in response to a revolt against the philosophical and didactic methods that more or less dominated medicine up to that time. Clinical psychology likewise is a protestant against a psychology that derives psychological and pedagogical principles from philosophical speculations and against a psychology that applies the results of laboratory experimentation directly to children in the school room (Witmer, 1907).

Who were “The Termites”?

When Lewis Terman adapted the Binet-Simon into the Stanford-Binet, it was used for more than the French government’s original purpose of identifying children who would struggle in school. Terman and colleagues expanded the use, such as using test results to predict the best placements for new military recruits. Terman was also interested in understanding giftedness.

In 1921, he began a now-famous longitudinal study of children identified as gifted. The children, referred to colloquially as “Termites” after Terman, were identified as highly intelligent and were followed through to their mid-lives. Many of the gifted children went on to achieve heights of education and accomplishment, winning awards and excelling in their careers. However, there were also examples of talent not being realized, which Terman attributed to factors such as personal obstacles and lack of opportunities. The outcomes for the “Termites” mirror research findings over 100 years since on correlates of intelligence today – although IQ is correlated with factors like school and career success, it is far from a perfect predictor, and many other factors contribute to those outcomes.

After Terman’s death, the study was continued by one of the “Termites” themselves!

Fumigating Vaginas & Prescribing Leeches: How were psychological disorders treated in the past?

Many psychological disorders, like depression and PTSD, are thought to have likely existed throughout human history. So, before we had our modern knowledge of biopsycholosocial factors that contribute to psychological disorders (e.g., genetic contributions to disorders, the role of neurostransmitters, how trauma affects the nervous system) informed by modern technology and research methods (e.g., brain imaging, longitudinal research to assess risk factors, randomized control trial research to assess interventions), what did people do when someone started behaving strangely?

Before modern science, people looked to whatever dominant belief systems existed in their time and culture to try to explain unusual behaviour. Often, this meant supernatural explanations. For instance, they might explain someone hearing voices as resulting from a curse or demonic possession. Whatever the explanation for the behaviour was, it usually led to the treatment in question. For instance, if someone was thought to be possessed by demons, resulting in their symptoms, they might undergo an exorcism. In ancient Greece, a woman’s psychological problems might be blamed on a “wandering uterus,” and she might have her vagina fumigated (!) or be told to have a baby to keep her uterus in place. People would sometimes be “bled” to treat their problems, originating from an idea that a series of bodily fluids (“humours”) becoming unbalanced created psychological issues. This could be done by making small cuts on the afflicted individual or by placing leeches (!) on them to allow the creatures to draw out some blood.

Some of these historical treatments were harmless, albeit ineffective (other than a potential “placebo effect”), but sometimes could be brutal or even deadly. For instance, exorcisms could involve “beating the demon out” or “starving the demon out”.

As can be seen from this discussion of history and important early influences, many diverse circumstances, from religion and military to early views of the physical body, helped shape the early origins of assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. So, what do all these factors lead us to today?

Setting the Context: Recognizing Missing Voices

As you may or may not have noted as you read through the above information on important people influencing the history of clinical psychology, they are mostly men from Western cultures. As a result, many voices are under-represented throughout the history of psychology, such as 2SLGBTQIA+, women, people of colour, and people from less individualistic cultures. This is an important limitation to keep in mind throughout this course!

Canada’s indigenous peoples are one of these underrepresented groups. Although there are many, distinct indigenous groups in Canada, with their own rich histories and traditions, indigenous peoples tend to approach health in a more holistic way and use cultural rituals as part of healing. Thus, mental health practices that are strongly influenced by Europeans and settlers may be less effective and potentially even harmful. This, combined with the intergenerational harms caused by longstanding racism and the residential school system, points to a strong need to welcome indigenous voices in all aspects of the health care system in Canada. Within the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls for Action, there are calls to “acknowledge that the current state of Aboriginal health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian government policies, including residential schools…”, “in consultation with Aboriginal peoples, to establish measurable goals to identify and close the gaps in health outcomes Calls to Action| 3 between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities” (which includes mental health, suicide, and addictions), “…provide sustainable funding for existing and new Aboriginal healing centres to address the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual harms caused by residential schools…”, and:

We call upon those who can effect change within the Canadian health-care system to recognize the value of Aboriginal healing practices and use them in the treatment of Aboriginal patients in collaboration with Aboriginal healers and Elders, where requested by Aboriginal patients.

The Future of Clinical Psychology

After covering the past and current practice of clinical psychology, we can think about the future of this profession. The future of clinical psychology depends on greater diversity among trainees and faculty to better reflect the populations they serve. As noted by Goghari (2022), White females remain overrepresented in clinical psychology programs, despite Canada’s rapidly shifting demographics—by 2036, immigrants are expected to make up 25% to 30% of the national population (Statistics Canada, 2017). To remain relevant and equitable, training programs must proactively recruit faculty and students from underrepresented groups. This focus on diversity would also mean reevaluating traditional admission metrics that may unintentionally disadvantage diverse applicants. Fostering diversity in training is essential not only for social justice, but also for ensuring that psychological care is culturally responsive and accessible to all communities.

An emerging and debated issue in the future of clinical psychology is the potential for prescription authority. Some part of the United States (e.g., New Mexico, Louisiana, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Idaho) currently grant prescription privileges to appropriately trained psychologists, with several other states introducing legislation to follow suit (Sepehry et al., 2025). This shift has shown positive impacts on access to care and treatment outcomes. For example, in states that have granted psychologists prescription authority, death by suicide decreased 5%-7% (Choudhury & Plemmons; 2023). Prescription authority, however, remains controversial. Major medical organizations like the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association oppose it, arguing that psychologists do not have sufficient training in psychotropic medications and psychopharmacology to warrant such an expanded scope (American Medical Association, 2009). Although Canada has not yet approved this expanded scope of practice, provincial associations in Ontario and British Columbia have advocated for it. A recent study by Sepehry et al. (2025) found that 88% of Canadian psychologists and psychology students believe prescription authority would improve service delivery for specific populations and enhance access to effective treatments. Notably, 65% said they would pursue the necessary training if prescription privileges became available in Canada.

Finally, to meet the growing demand for mental health services, the field of clinical psychology must also prioritize increasing its workforce. Currently, only about 1% of the global health workforce is dedicated to mental health, and psychologists make up just 7% of that small fraction (Bradley, 2019; Goghari, 2022; Mikail & Nicholson, 2019). Innovative solutions are needed to expand training opportunities and output of trained mental health professionals. The development of PsyD programs has emerged as one response to the mental health care crisis, aiming to train more practice-oriented clinicians. These programs have become particularly popular in Atlantic Canada, with a PsyD program at Memorial University in Newfoundland, UPEI, and a new program in development at Mount Saint Vincent University in Nova Scotia. Additionally, Dalhousie University recently opened the Dalhousie Centre for Psychological Health, which offers training opportunities for PhD students and four residency positions for students at the end of their degree. Programs like this, coupled with targeted incentives (e.g., scholarships for students who commit to practicing in rural or remote areas) could help bolster the number of psychologists where they are needed most. Similar to models used in nursing (e.g., Mbemba et al., 2013), these approaches might help ensure more equitable access to psychological care across Canada.

Media Attributions

- CPA

- therapist © Nick Youngson is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Map

- type of practice

- typeofpractice

- professional time

- Lewis Madison Terman, American psychologist and pioneer in educational psychology © Unknown Author is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pill bottle spilled over © Mpelletier1 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

A training model that emphasizes both research and clinical practice, preparing psychologists to contribute to and integrate science into their clinical work.

A model focused more on clinical practice than research, training psychologists to apply existing knowledge effectively in clinical settings.

The formal recognition of a training program by an authoritative body, ensuring that the program meets established standards of quality in education, training, and ethical practice.

A set of professional guidelines that outline ethical standards and responsibilities for psychologists to ensure safe, respectful, and competent practice.

How to make an ethical choice when a dilemma or conflict between ethical guidelines arises.

Identifying and a mental health disorder based on symptoms, such as those outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR).

A group of health professionals from different fields working together on a patient’s care.

The boundaries within which a health care professional can legally and ethically work, based on their education and training.

The legal right to prescribe medications.