2 Research Methods in Clinical Psychology

Madison Conrad and Robson M. Underwood

Introduction

Clinical psychologists go through many years of school and extensive training, which can take 10+ years for those pursuing a PhD! During all those years, clinical psychologists complete coursework, clinical training, and a lot of research. Psychologists are trained using the scientist-practitioner model, meaning they are both clinicians and researchers. This research expertise is crucial to ensure they can provide people with evidence-based mental health care. In this chapter, you will learn how clinical psychologists conduct research, from the methods they use, the topics they investigate, to important ethical considerations they keep in mind.

Learning Objectives

LO 1: Understand the areas of interest often studied by clinical psychologists, and how research questions are formulated.

LO 2: Explain the significance of ethical guidelines in research and identify key steps taken throughout the research process to ensure ethical standards are upheld.

LO 3: Compare and contrast research designs.

LO 4: Identify key factors in developing new clinical psychology measures and explain how to adapt them to the generalizability of a given population.

LO 5: Explain how clinical psychologists apply research in practice, and how to assess its impact on client outcomes.

How do Clinical Psychologists generate research questions and hypotheses?

To understand research methods in clinical psychology, we must begin by discussing the need for research and how research hypotheses are formulated. As humans, we cannot rely solely on common sense as a guide to making appropriate decisions in a clinical setting, as there are often inconsistencies in how people process information and make decisions. While these inconsistencies may be minor in everyday life, in clinical settings, they can have a profoundly impactful effect on people’s lives. Two good examples of how research should inform practice are the evolution of the treatment for schizophrenia spectrum disorders. For example, in the 1800s, individuals who exhibited psychotic symptoms were often constrained to asylums. “Effective” treatments at the time included spinning them in chairs or dumping them in a frozen lake. Even in the early 1900s, it was believed that insulin comas and frontal lobotomies were effective in the treatment of schizophrenia (Tueth, 1995); however, this could result in personality changes, injuries and even death. As research evidence became available (as well as ethics), these approaches have been replaced by treatments that are demonstrated to improve the lives of people with schizophrenia, including medication and psychosocial therapy (Guo et al., 2010; MacDonagh et al., 2017).

The observations clinicians can make in clinical practice can be a rich source of possible research hypotheses. Research ideas, however, can be generated from a variety of sources, including everyday experiences and knowledge of previous scientific literature. An example prominent in clinical forensic settings is the development of our understanding of psychopathy (See Box A). Regardless of where the research idea originates, a crucial aspect of the research process involves developing a research hypothesis, which is generally tested using the scientific method. The scientific method provides a structured framework for investigating research questions and testing hypotheses. It typically involves the following steps:

- Observation

- Formulating a hypothesis

- Experimentation/data collection

- Analyses

- Conclusion

Madness without Delirium

What do Clinical Psychologists Research?

As mentioned at the start of the chapter, clinical psychologists in Canada are often trained under the scientist-practitioner model. This model first emphasizes training in research and scientific inquiry, followed by practice. The professional standards and ethics of clinical psychologists in Canada are set by the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA), which is founded on integrating science into practice. These principles ensure that people receiving services are receiving services founded in psychological science, referred to as evidence-based practice. Evidence-based practice can be defined as the integration of empirical and available research evidence to inform the clinical decision-making process across all stages of treatment in a manner that is responsive to the client’s characteristics, culture and preferences. The integration of evidence-based practice is an ongoing process designed to maximize treatment benefits, minimize the risk of harm, and ensure the delivery of cost-effective care (Dozois et al., 2014). These are crucial practices and considerations that clinical psychologists should use. However, you might wonder where the evidence comes from or what type of evidence clinical psychologists use.

Canadian Psychological Association Definition of Evidence-Based Practice

“Evidence-based practice of psychological treatment involves the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of the best available research evidence to inform each stage of clinical decision making and service delivery (Dozois et al., 2014).”

While many people with PhDs in psychology conduct various types of research, clinical psychologists often focus on research and science that can be applied to four key areas: psychopathology, assessment, treatment, and prevention. Clinical psychologists can research the biological, psychological and social factors that might contribute to psychopathologies, such as mood disorders, psychotic disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, which can allow us to understand why and how these disorders emerge, how they affect individuals and how they can vary. They could ask a question such as, “Does early social media use predict depression in adolescence?” Research on assessment can involve designing and validating measures and tests to evaluate symptoms. Research on assessment can allow clinicians to arrive at an accurate diagnosis, formulate an effective treatment plan, and monitor progress over time. For example, “How accurate is measure X at assessing generalized anxiety?” Treatment can involve applying and studying methods to alleviate distressing symptoms and improve mental well-being. Clinical psychologists often conduct studies on the effectiveness of interventions allowing clinicians to understand the most supported treatment for a given presenting concern. For example, they might ask, “Is Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) more effective than Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for treating borderline personality disorder?” Clinical psychologists can also research prevention, which involves identifying risk and protective factors that are related to the likelihood of psychological disorders developing in the first place. They might study how early life experiences, schooling, social environments, and genetic predispositions contribute to the development and progression of mental health outcomes. Asking questions such as, “Does early education on harm reduction reduce rates of addiction?” Through research in psychopathology, assessment, treatment and prevention, clinical psychologists contribute meaningfully to the profession and treatment of mental health.

Ethics in Clinical Psychology Research

Throughout the history of clinical psychology, psychologists have conducted some controversial experiments that have failed to stand the test of time and fail to meet many present-day ethical codes and guidelines. An example of this is Watson and Rayner’s Little Albert experiment. Nowadays, clinical psychologists are required to follow strict guidelines to ensure their research is ethically and scientifically sound.

Little Albert: A big lesson in bad ethics

In 1920, Watson and Rayner conducted the infamous “Little Albert” experiment. They selected a baby boy, who appeared healthy with a stable disposition, who came to be known as Little Albert. He was then subjected to a series of routine “emotional tests” to provide evidence that emotional responses could be classically conditioned. Watson and Rayner can even be quoted as saying, “We felt that we could do him relatively little harm by carrying out such experiments” (Watson & Rayner, 1920, p.2). While they were at first hesitant about conducting the experiment, they justified it because they assumed fear responses would naturally occur throughout Albert’s life anyway. Then, at just 11 months old, they presented Albert with a white rat and every time he touched the animal, they would strike a bar, creating a loud noise. Eventually, Albert began to cry from just seeing the rat. Albert was then presented with a variety of other stimuli, like rabbits, dogs, fur coats, and even a Santa mask, all of which produced similar fear responses. Unfortunately, Albert was removed from the study before the researchers could attempt to extinguish the conditioned fear response. The ultimate fate of Little Albert remains largely unknown, but Watson and Rayner suggested the responses are likely to persist indefinitely (Watson & Rayner, 1920).

In 1920, Watson and Rayner conducted the infamous “Little Albert” experiment. They selected a baby boy, who appeared healthy with a stable disposition, who came to be known as Little Albert. He was then subjected to a series of routine “emotional tests” to provide evidence that emotional responses could be classically conditioned. Watson and Rayner can even be quoted as saying, “We felt that we could do him relatively little harm by carrying out such experiments” (Watson & Rayner, 1920, p.2). While they were at first hesitant about conducting the experiment, they justified it because they assumed fear responses would naturally occur throughout Albert’s life anyway. Then, at just 11 months old, they presented Albert with a white rat and every time he touched the animal, they would strike a bar, creating a loud noise. Eventually, Albert began to cry from just seeing the rat. Albert was then presented with a variety of other stimuli, like rabbits, dogs, fur coats, and even a Santa mask, all of which produced similar fear responses. Unfortunately, Albert was removed from the study before the researchers could attempt to extinguish the conditioned fear response. The ultimate fate of Little Albert remains largely unknown, but Watson and Rayner suggested the responses are likely to persist indefinitely (Watson & Rayner, 1920).

Canadian Psychological Association Code of Ethics

The CPA code of ethics is a set of ethical principles, values, and aspirational guidelines for the professional behaviour of Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) members, which is often used in conjunction with provincial standards. The code provides guidance for psychologists in their day-to-day work, offers a framework for resolving ethical dilemmas, and can assist in arbitrating complaints against psychologists. The CPA code of ethics applies to every single member of the Canadian Psychological Association, regardless of their role. This includes, but is not limited to, researchers, practitioners, scientist-practitioners, students, administrators, employers, and others (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017). The code consists of four main pillars, each one associated with several ethical standards. It is the psychologist’s role to ensure they are familiar with the code of ethics, apply and uphold it, and ensure others are doing so as well.

Psychologists may encounter ethical dilemmas or issues that need to be resolved quickly, often with no straightforward, correct answer. When faced with an ethical dilemma, psychologists are expected to consider all four pillars; however, in many circumstances, this may not be possible, especially in situations where the ethical principles conflict, making it impossible to give each principle equal consideration. As such, the principles have been ordered according to priority, each should be given in such situations (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017). Due to the complexity of many ethical dilemmas, the CPA has outlined 10 steps for ethical decision-making to consider in conjunction with the code of ethics.

1. Respect for the dignity of persons and peoples

Throughout any given day, a psychologist interacts with a variety of individuals, including clients, families, students, colleagues, and third parties (such as schools, courts, or insurance companies). It is the psychologist’s ethical duty to maintain relationships with these individuals that are founded on the basic principle of respect for their dignity. This fundamental ethical obligation is to uphold the rights, respect, and dignity of all individuals regardless of external factors (i.e., background). The core principles of the pillar include general respect, general rights, non-discrimination, fair treatment and due process, informed consent, freedom of consent, protections for vulnerable individuals and groups, privacy, and confidentiality.

Informed consent

Obtaining informed consent is crucial to the process of conducting ethical psychological research. Consent for research must be informed, freely given, and ongoing. Research cannot begin before consent is obtained, and participants should be given the opportunity to withdraw their consent at any time (Health Canada, 2024).

Consent should be voluntarily given, meaning the participant has chosen to participate in research without undue influence or coercion (Health Canada, 2024). Participants must not be pressured to participate by an authority figure, nor should they receive excessively large incentives to participate. Imagine your university professor strongly encourages you to participate in a study they are running. The research topic makes you uncomfortable, so you are hesitant to participate, but you also know your professor is in charge of your final grade. Even if you agree to participate, your consent was not voluntarily given because of the pressure your professor put on you.

Furthermore, considering what, if, and how you are going to incentivize participation in your research is important. The Tri-Council policy neither encourages nor discourages the use of incentives to encourage participation in research; however, it is the researcher’s responsibility to justify the use of incentives to the Research Ethics Board (REB) (Panel on Research Ethics, 2022). Incentives should be sufficient to encourage participation, but not so excessive as to cause people to disregard the potential risks associated with participation (Panel on Research Ethics, 2022). For consent to be truly voluntary, participants should be able to withdraw it at any point in time, regardless of reason. Furthermore, if a participant chooses to withdraw their consent, they shouldn’t suffer any consequences and should still be compensated for their participation.

A critical part of the consent process is that it is a fully informed decision. Researchers should provide all participants with all necessary information to enable them to make a fully informed decision about participating in the research.

Information generally required for informed consent

| 1. Invitation to participate |

| 2. The purpose of the research, and general info (e.g., expected duration, description of research, and responsibilities) |

| 3. Description of risks and benefits |

| 4. Assurance that they are free to withdraw at any time, will be kept up to date with any new relevant info, and will be given the right to withdraw that data |

| 5. Information regarding the potential commercialization of research findings or any conflicts of interest |

| 6. How the participants will/won’t be identified, and any planned measures for disseminating the research results |

| 7. Identifying and providing contact information for a qualified representative who can answer questions |

| 8. Identifying and providing contact information for the individual to contact with regard to potential ethical issues |

| 9. Information about what will be collected from the participants and why, who will be able to access it and how confidentiality will be protected |

| 10. Information about payments (e.g., incentives, reimbursement, compensation) |

| 11. Statement saying that by consenting, participants have not waived any rights to legal recourse in the event of research-related harms |

| 12. For clinical trials, information on stopping rules and when participants may be removed from the trial |

(Panel on Research Ethics, 2022)

After being presented with all necessary information, participants should be given sufficient time to consider their options and ask any questions they may have. Additionally, all information should be presented in an accessible way (considering their age, education level, reading ability, language abilities, etc) (Panel on Research Ethics, 2022).

What steps would you take to make informed consent accessible to:

- A 7-year-old child

- A person with reading difficulties

- Someone who is not comfortable with English

Lastly, consent should be ongoing and maintained throughout all stages of the research. Should any information be changed or new information arise during any stage of the research process, both the participants and the Research Ethics Board (REB) should be informed. This allows participants to reconsider their consent in light of new information. For example, imagine you consent to a research study that you were told would investigate how personality traits influence the formation of friendships. However, at the end, the researchers debrief you and reveal that they were investigating your political orientations. After discovering this new information, you should be given the opportunity to reaffirm or withdraw your consent (Panel on Research Ethics, 2022).

Test yourself!

Privacy and confidentiality

Would you walk into your professor’s or boss’s office right now and tell them all of your deepest, darkest secrets? Probably not, however, this does illustrate why privacy and confidentiality are so important in research. If you were asking people about personal topics and they knew their responses were not private, they would likely not be truthful, making any data you collect essentially useless.

Privacy risks can arise at any stage in the research process, and researchers are responsible for complying with all legal and regulatory requirements regarding privacy and confidentiality. It is essential to consider how identifiable the information being collected is, as ethical concerns regarding privacy decrease significantly the more difficult it is to associate the information with a particular individual.

Types of information

| Type of information | Description | Example |

| Directly identifying information | Information which identifies specific individuals through direct identification | Name or social insurance number (SIN) |

| Indirectly identifying information | Information which can reasonably be expected to identify an individual through a combination of indirect identifiers | Date of birth or Address |

| Coded information | Information where direct identification is removed and replaced with a code | Using a participant ID number |

| Anonymized information | The information is stripped of direct identifiers, and the risk of re-identification is very low | Information where no code is kept to re-link the information |

| Anonymous information | The information never had identifiers associated with it | Anonymous surveys |

(Panel on Research Ethics, 2022)

Ideally, only anonymous or anonymized data is collected; however, if this is not possible, the next best option would be to use de-identified data. If you were to scan a QR code on a poster that directs you to an anonymous survey and collects no personally identifiable information (i.e., email addresses, names, etc.), that would be considered anonymous data. However, if you took the same survey and it collected info like your name or email for compensation purposes, that would be identifying information. Often, researchers need to collect identifiable information for a variety of reasons. The best course to minimize privacy risks associated with identifiable information is to have a trusted third party (independent of the researcher) de-identify it before providing the data to the researchers. If none of the above options are accessible, the researchers themselves should attempt to de-identify the data as soon as possible (Panel on Research Ethics, 2022).

Research in clinical psychology is especially likely to cover sensitive topics. This requires a significant amount of trust between the participant and researcher, which hinges on the promise of confidentiality. There are several situations in which a researcher (or clinical psychologist) is legally and/or ethically obligated to breach confidentiality (Panel on Research Ethics, 2022). Situations in which confidentiality must be broken involve instances where the client poses a significant risk to themselves or others, the disclosure of abuse or knowledge of abuse of vulnerable populations, a court subpoena, or a third-party client (i.e., an insurance company) (Nova Scotia Board of Examiners in Psychology (NSBEP), n.d.).

Test yourself!

Protection of vulnerable populations

The Canadian Code of Ethics specifically outlines the importance of protecting vulnerable groups, which can include children, adults with diminished capacity, individuals belonging to historically marginalized communities, and trainees. This guideline helps ensure research injustices are less like to occur. For example, between 1932 and 1972, the U.S Public Health Service conducted a study intending to investigate the effects of untreated syphilis. Informed consent was never obtained from participants, who were limited to Black men aged 25 and older. These men were never told they had syphilis and were never treated, even after a cure had been found, and as a result, many people died or infected others (CDC, 2024). Similarly, women have been excluded or underrepresented in research. Women’s bodies were considered atypical and deviant from the norm of men’s bodies (Balch, 2024). The lack of female representation in research has resulted in innumerable adverse health outcomes for females. Just to name a few, women experience adverse reactions from medications at twice the rate of men (Anwar, 2020). Hip replacements are significantly more likely to fail in women compared to men (Inacio et al., 2013), and women are more likely to die within five years of a heart attack compared to men (Understanding the Heart Attack Gender Gap, 2016). These examples illustrate why the principle of Justice outlined in the TCPS-2 (2022) is so important.

“The principle of Justice holds that particular individuals, groups or communities should neither bear an unfair share of the direct burdens of participating in research, nor should they be unfairly excluded from the potential benefits of research participation. Inclusiveness in research and fair distribution of benefits and burdens should be important considerations for researchers, research ethics boards (REBs), research institutions and sponsors. Issues of fair and equitable treatment arise in deciding whether and how to include individuals, groups or communities in research, and the basis for the exclusion of some.”.

(Panel on Research Ethics, 2022)

While it is essential not to exclude or overrepresent populations based on their vulnerability, there are steps that researchers can and should take to ensure the protection of vulnerable and/or marginalized populations. As a result, the following section outlines considerations when conducting research with people who are incarcerated, which represents a vulnerable population in research. Other examples of vulnerable populations include youth, those with limited decision-making capacity, Indigenous communities, etc.

People who are incarcerated

When conducting research with people who are incarcerated, it is crucial to consider who and what may be overrepresented in forensic populations. In Canada, indigenous people are overrepresented in correctional institutions. Despite only accounting for 5% of the adult population, indigenous people account for 28% of people serving federal sentences. Further, indigenous women account for 50% of all federally incarcerated women (Public Safety Canada, 2023). Additionally, a significant number of incarcerated people experience mental health concerns requiring intervention while in a correctional institution (Silva et al., 2017). Conducting research in forensic settings poses another threat to informed consent. Due to the inherent and unavoidable power imbalance between the incarcerated person and others (researchers, correctional staff, etc.). Which leads us to the question: How are incarcerated people able to give voluntary, informed consent? To address this, researchers must be aware of the current state of the correctional system and how that may affect the incarcerated person’s willingness to participate in research (Silva et al., 2017). As previously laid out in the CPA code of ethics, psychologists should do no harm. This extends beyond physical harm, and the research should not put participants at risk of social, emotional, economic, or legal harm (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017; Regehr et al., 2000). Furthermore, incarcerated people should not be exploited or overburdened with the risks associated with participating in research (Silva et al., 2017).

Future reading – How to protect vulnerable populations in research

General

-

Vulnerability in Research 101 | Research In Action | Advancing Health. (n.d.). Retrieved June 30, 2025, from https://www.advancinghealth.ubc.ca/research-in-action/research-with-vulnerable-populations-101/

-

Quinn, C. R. (2015). General considerations for research with vulnerable populations: Ten lessons for success. Health & Justice, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-014-0013-z

2SLGBTQIA+

-

Coon, J. J., Alexander, N. B., Smith, E. M., Spellman, M., Klimasmith, I. M., Allen-Custodio, L. T., Clarkberg, T. E., Lynch, L., Knutson, D., Fountain, K., Rivera, M., Scherz, M., & Morrow, L. K. (2023). Best practices for LGBTQ+ inclusion during ecological fieldwork: Considering safety, cis/heteronormativity and structural barriers. Journal of Applied Ecology, 60(3), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14339

-

Veldhuis, C. B., Cascalheira, C. J., Delucio, K., Budge, S. L., Matsuno, E., Huynh, K., Puckett, J. A., Balsam, K. F., Velez, B. L., & Galupo, M. P. (2024). Sexual orientation and gender diversity research manuscript writing guide. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 11(3), 365–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd000072

2. Responsible Caring

Psychologists have a basic ethical expectation that any activities they conduct will benefit society, and at the very least, should not cause harm. This responsibility to protect people from harm extends beyond just the individuals or groups psychologists see or research, but to anyone who might be affected in some way by the psychologist’s actions. Clients/participants should be protected from harm to their personal and social relationships, as well as from fear, humiliation, and feelings of self-worth. But what happens when a treatment involves being exposed to potential psychological harm? Think of exposure and response prevention; in order for the treatment to work, the clients must continuously expose themselves to the very thing that causes them the most fear and anxiety. At the same time, this treatment is the gold-standard evidence-based approach that is likely to help in the long term. The following elements of responsible caring protect client/participants and ensure psychologists are engaging in responsible caring (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017).

3. Integrity in relationships

Although principle three should be given the third highest weight, many aspects of this pillar are critical to consider when conducting research. Generally, psychologists should aim to maintain the highest level of integrity possible in their relationships. This involves accuracy, honesty, objectivity/lack of bias, openness, avoidance of incomplete disclosure and deception, avoidance of conflict of interests, reliance on the discipline, and extended responsibility (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017).

Avoidance of incomplete disclosure and deception

To minimize participant effects, such as socially desirable responding, many psychological studies employ deception; however, there are ways to ethically deceive participants while still protecting their interests and maintaining their dignity. Ideally, researchers should opt to use the minimum necessary deception and debrief participants as soon as possible. Additionally, the deception should never prevent participants from understanding the risks associated with participating. If possible, other methods that don’t involve deception should be explored. The debriefing should outline the true intention of the study, ensure that participants understood the need for deception, and clarify any questions that may have arisen. Participants should also be given the option of removing their data after learning the true purpose of the research (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017).

Principle IV: Responsibility to Society

Responsibility to society is the fourth and by far the most aspirational pillar. This pillar includes the development of knowledge, engaging in beneficial activities, respect for society, development of society, and extended responsibility. Generally, this pillar emphasizes the importance of contributing to the public good, accountability, developing the profession, and considering the broader impact of your actions (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017 ).

Learn more!

Types of Research Designs

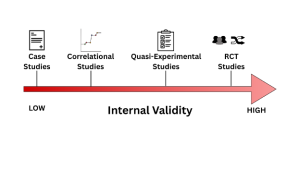

As we will cover in the following sections, various types of research designs are employed in the field of clinical psychology. The majority of the mentioned designs are rooted in Western science; however, we will also discuss other ways of knowing that stem from Indigenous Canadian practices. Research designs can vary in the number of participants involved, as well as in their strength of external and internal validity. While it can be argued that certain research designs may be superior to others, it is essential to acknowledge that all designs have both advantages and disadvantages. Clinical psychology involves the use of evidence-based practice, and the research associated with this practice can range from a single case study to a multi-year experimental design, both of which can make impactful contributions to the profession. Meaningful research is cumulative in that it often generates new ideas and questions. In the following sections, we will discuss a variety of research designs used by Clinical Psychologists, ranging from single, intriguing participants to very rigorous and complex experimental designs. The different types of research designs that we will cover are displayed in Figure 3.

Case Studies are an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event, illustrating a new or rare observation or treatment innovation. This type of research design provides a valuable format for making introductory connections between events, behaviours or symptoms that have not often been addressed or mentioned in research before. Case studies are fascinating because they can be the initial testing ground for treatments and innovations, drawing professionals to a psychological phenomenon. An example of the use of case studies that we already mentioned in this chapter is Harvey Cleckley’s investigation into psychopathy. Dr. Cleckley noticed a subset of clients that presented with antisocial symptoms extending beyond the normal presentation; this led him to release a book called The Mask of Sanity, which is a collection of 15 detailed case studies of clients he was seeing. While one case or even 20 can benefit and expand our understanding of certain psychological phenomena, the most important aspect of case studies is their potential to generate hypotheses. A trade-off for case studies is their lack of external and internal validity. Case studies have problems with internal validity due to their lack of control for confounding variables . Case studies also have problems with external validity because they often lack generalizability. While they do not allow for the rigorous testing of a hypothesis, they can draw attention to a phenomenon and persuade further investigation through more experimental methods.

Correlational Designs are non-experimental research designs that measure and assess the relationship among variables without manipulating them. The goal of this design is to investigate the association between variables. For example, a researcher might use this design to determine if there is a correlation between social media use and anxiety levels in adolescence. One of the most important considerations of this type of research design is that it does not establish a cause-and-effect relationship. A causal statement about the association is the most common error in correlational designs. You might have heard the phrase “correlation is not causation.” This statement holds because correlational designs do not involve manipulation or control of variables, and therefore cannot establish causality. While there remain problems with internal validity, correlational designs often have moderate to high external validity because they can consist of diverse, large samples and often include up-to-date, real-world data. Overall, a correlational design is a common non-experimental research design that allows us to understand associations between variables without making a causal claim.

Correlation or Causation? The Third Variable Problem

Consider the correlation between ice cream sales and drowning deaths. While the two variables appear to be associated, there is another third unmeasured variable (hot weather) likely responsible for the fact that when ice cream sales increase, so do drowning deaths and vice versa. This example demonstrates why it is especially important not to assume causality from correlational designs.

Like correlational studies, there are other research designs that are informative but do not assess causality. Some are descriptive, such as the study of incidence or prevalence of a disorder within a population. Others can be used to examine the underlying structure of a measure or a set of measures, a technique known as factor analysis. A Factor Analysis is a statistical procedure that identifies underlying dimensions (Factors) in a set of variables, test items or measures. These can be used when psychologists develop measures for different psychological concepts to determine which items contribute meaningfully to the concept or disorder. For example, say you wanted to develop a tool to assess for depression; you would want all the items on the tool to positively correlate with symptoms that are common with depression and not correlate with other types of symptoms. Factor analysis helps reveal which items on a tool are effective and which are not.

Now, say a researcher wants to study the psychological impact of child abuse. In this case, you cannot assign certain participants to be abused and others not, as it would be unethical; this is where quasi-experimental designs come in. Quasi-experimental designs are a research design that involves some form of manipulation by the researcher, examining the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable without randomly assigning participants to conditions or groups. Unlike true experiments, they lack random assignment, which makes them less effective in controlling for confounding variables. A cost-effective and frequently used quasi-experimental design involves comparing two previously established groups of participants, with one receiving an intervention and the other not, and then collecting and analyzing data after the intervention has been administered. However, there is a significant weakness with this approach, as the two groups may be very different from one another before the intervention is conducted, which could affect the results. While this type of research design has some flaws, it can be very useful for investigating concepts that may be unethical or impractical to examine under a true experiment.

Experimental designs are research designs used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables, involving both random assignment and experimental manipulation. This research design is best suited to prevent threats to internal validity because it is more rigorous in its procedures. The gold standard of experimental designs in clinical psychological research is the Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) (Hariton, 2018). Randomized Controlled Trials are a type of experimental design for testing the effectiveness of interventions, treatments, or therapies in which participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more conditions (see Figure 2). The “randomized control” aspect of this experimental design involves examining the efficacy of an intervention compared to a control group, where participants are randomly assigned to a treatment or control group (no-treatment group). In clinical research, the control group is often referred to as the waitlist condition, in which participants do not receive any form of intervention until after the research is complete. Other times, the control group receives a placebo, such as a psychoeducation or a sham therapy, to control for the placebo effect. Through randomization, these designs reduce bias and provide rigorous tools to examine the causal relationship between an intervention and an outcome, as randomization balances participant characteristics (both observed and unobserved) between groups. Participants must not be aware of which group they are being assigned to, a technique often referred to as concealment or blinding, to further minimize bias (Hariton, 2018). While randomized controlled trials are considered the gold standard for experimental designs, they have several drawbacks, including being costly and time-consuming, especially when a large sample size is required. They also have ethical limitations, such as it being inappropriate to withhold treatment from a control group. Additionally, they have some limits to generalizability, as strict controls may not accurately reflect the real world, resulting in lower external validity. We will discuss external and internal validity further in the later sections of the chapter.

The previously mentioned research designs are all common and useful types of designs frequently used in academic settings. However, there is a type of research design that can be particularly applicable to clinical psychologists working in a clinical practice called a service evaluation. A service evaluation is a type of research used to assess the effectiveness of a psychological service, program, or intervention, involving data collection on aspects of current clinical practice. Service evaluations are often done to evaluate and improve the practice. These can be assessed through qualitative or quantitative methods, such as scoring on psychological assessments before or after treatment or feedback surveys. Service evaluations have not only been shown to improve clinical performance but also to enhance survival rates (Ozdemir et al., 2015; Rochan et al., 2014). It is important to note, however, that while clinical psychologists are ideally positioned to conduct high-quality research on service evaluation, this is often rarely done (Smith & Thew, 2017).

Test yourself!

Two-Eyed Seeing

Etuaptmumk, which translates to “Two-Eyed seeing,” was originally coined by Albert Marshall, a Mi’kmaw Elder, advocate, and leader. Two-Eyed seeing is a guiding principle which states “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing … and learning to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all.” (Moore, 2023). This concept is important to keep in mind, as researchers can prioritize both Western scientific rigor and traditional indigenous knowledge, without negating one for the other.

Suggestions for those engaging with two-eyed seeing

Non-indigenous researchers aiming to integrate two-eyed seeing into their research require the support of at least one individual with indigenous knowledge and perspectives. This will enable a more seamless integration of both worldviews (Wright et al., 2019). Engaging with multiple viewpoints can be time-consuming, particularly when one does not adhere to formal funding agency guidelines, so patience and relational skills are of the utmost importance (Hall et al., 2015). Furthermore, effective communication skills and prioritizing equitable relationships are essential for engaging with others using the two-eyed seeing approach (Wright et al., 2019). It is also critical that the research does not perpetuate negative stereotypes and promises the resilience of indigenous people. Lastly, individuals must be open to change and willing to engage in self-reflection.

Watch a short video on how Two-Eyed Seeing is being applied in healthcare

Video by ACHH Initiative, “ACHH Video: Two-Eyed Seeing Approach,” published on YouTube, 2018.

Future readings – Working with and protecting Indigenous populations in research

- TCPS 2 (2022) – Chapter 9: Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada

-

Morisano, D., Robinson, M., Rush, B., & Linklater, R. (2024). Conducting research with Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Ethical and policy considerations. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1214121

-

Morisano, D., Robinson, M., Rush, B., & Linklater, R. (2024). Conducting research with Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Ethical and policy considerations. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1214121

-

Wright, A. L., Gabel, C., Ballantyne, M., Jack, S. M., & Wahoush, O. (2019). Using Two-Eyed Seeing in Research With Indigenous People: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1609406919869695. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919869695

-

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books ; University of Otago Press. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/hol052/98030387.html

Research Synthesis

Synthesizing findings across studies helps clinicians form a more comprehensive understanding of treatment effects, thereby reducing their reliance on a single case or even a single RCT study. This is possible because of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

A systematic review is a structured and comprehensive synthesis of multiple research studies on a particular treatment or issue aimed at determining the findings of all relevant evidence. They aim to minimize bias by using transparent criteria for study selection and quality assessment, which can later inform a meta-analysis. The process of systematic reviews involves identifying a set of questions that will direct the literature search across multiple databases, following specific criteria such as a predetermined sample size or a specific population. The results are then interpreted and summarized, considering the limitations of each study, as well as the limitations of the systematic review itself. In some cases, if the studies are similar enough in terms of population, intervention, and study design, they can be analyzed using a meta-analysis.

A meta-analysis statistically combines the quantitative results of research studies in a specific area to determine the overall effect. Effect sizes from individual studies can be combined in a meta-analysis to get a better sense of the true effect. An effect size is a quantitative measure of the magnitude of a relationship (e.g., how much of a difference a treatment might make in a health outcome). For example, if 20 studies in a meta-analysis all get the same results, we can be more confident in their conclusions relative to the findings of a single study. In psychology, we often use Cohen’s d as a measure of effect for t-tests and ANOVA and Pearson’s r for correlational analysis. Meta-analyses help reduce biases from single studies, as well as publication bias, as studies that were not published due to null results (i.e., not statistically significant) can be included. Ultimately, by synthesizing large amounts of information and data, systematic reviews and meta-analyses enable researchers to get a better sense of the true effect across many studies, and to be more confident in them if researchers keep finding the same results.

Selecting Participants

Internal vs External Validity

Internal validity refers to “the degree to which a study or experiment is free from flaws in its internal structure and its results can therefore be taken to represent the true nature of the phenomenon” (APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.). In other words, internal validity pertains to the soundness of results obtained within the controlled conditions of a particular study, specifically concerning whether one can draw reasonable conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships among variables. Essentially, how well the study was designed (i.e., using psychometrically sound measures, a valid sampling method, and a proper procedure) affects the extent to which we trust the results to accurately capture what they intended to.

Conversely, yet related external validity refers to “the extent to which the results of research or testing can be generalized beyond the sample that generated them.” (APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.). Essentially, the more specific your sample is, the less it will generalize to other populations beyond it. Say you are trying to investigate whether a newly developed intervention for ADHD is effective. Suppose you only test white male participants between the ages of 8 and 10. In that case, your study will have low external validity compared to a large, diverse sample that includes participants of various genders, ethnicities, ages, socioeconomic statuses, and other characteristics.

Unfortunately, notwithstanding researchers’ best efforts, there is no such thing as a perfectly designed study. When researchers address threats to internal validity, generally, they increase the risk of threats to external validity, and vice versa. Researchers must balance threats to internal and external validity as best they can; however, priority is often given to internal validity (Hunsley & Lee, 2017). We will revisit internal and external validity shortly.

Test yourself!

Population vs Sample

Many risks to internal and external validity can be mitigated by considering who or what you are trying to research. This often-overlooked step is crucial for conducting ethical and valid research. Your population refers to the entire group to whom the results of your research will be generalized. For example, if you wanted to investigate whether dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) was more effective than Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for young adults with borderline personality disorder (BPD) aged 18-25. In this example, the target population would be every single young adult aged 18-25 with BPD. As much as we wish, it would not be possible to have every single member of a population participate in our research study, so we settle for a (ideally) representative sample. A sample is a subset of individuals drawn from a population of interest to make inferences about the population (APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d .). Consider that you are investigating the study habits of students at your university. The target population is students at your university. For your study, you have decided to recruit 60 students for your sample. You walk into an intro psych class, and all of a sudden, 60 people sign up for your study right then and there. Perfect! You have enough people to do your study, and your supervisor is going to be so impressed with you. While you did recruit a sample of your population, it is not a representative sample. A representative sample is a sample which shares the essential characteristics of the population from which it was drawn (Gorvine et al., 2017). Returning to our study habits example, a representative sample would need to include individuals with diverse gender identities, different academic programs, various ethnicities, different age groups, and different years of study, among other characteristics. Essentially, the diversity of your sample needs to reflect the diversity of your population.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Another threat to the generalizability of RCTs is the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria they typically employ. Inclusion/exclusion criteria enable researchers to ensure that what they are measuring is truly what they intended to (i.e., good for internal validity). However, to achieve this, they often have to exclude a number of participants due to strict exclusion criteria (Khorsan & Crawford, 2014). Often, researchers will exclude clients with comorbidities, which is particularly problematic in clinical psychology research. Approximately ⅓ of adults with a mental disorder had one or more other co-occurring disorders (Forman–Hoffman et al., 2018). Depending on the specific disorder, this is likely an underestimate. Ronconi et al., (2014) investigated the inclusion and exclusion criteria in RCTs of psychotherapy for PTSD. They found that the most commonly used exclusion criteria prevented clients with psychosis, substance dependence, bipolar disorder, and suicidal ideation from participating in RCTs. Other exclusion criteria included anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and “complicating life circumstances”. Logically, this may make sense, if you want to ensure a treatment for PTSD is really effective, you want to ensure your participants only have PTSD. However, consider the external validity implications of excluding a majority of participants based on comorbid disorders. A 2020 study revealed that the vast majority (78.5%) of people diagnosed with PTSD had at least one or more comorbid disorders as well (Qassem et al., 2021).

Consider

RCTs and clinical psychology research more broadly typically lack cultural integrity and fail to consider other ways of knowing. Ju et al., (2017) define cultural integrity as meaning indigenous cultural knowledge is central to the research design, execution, and resulting recommendations. Within an indigenous context, RCTs lie outside traditional indigenous understandings of health and wellness (Eades et al., 2012). A systematic review conducted by Esgin et al., (2023) revealed that it is feasible to design a study with strong cultural integrity, along with scientific and methodological rigor.

Regardless of research questions or methods, it is critically important that you consider who you are including or excluding from your research and why. Reflect on the earlier discussion in this chapter about ethically including vulnerable populations in research and how it may be relevant when recruiting your sample.

Consider – Determining Eligibility

When considering who to include or exclude from research, it is essential to consider the research question. This might seem silly, but selecting your sample requires you to critically evaluate your goals and be very precise. Consider the research question “What are the psychological effects of balancing a career with being a mother?”. Now think critically about who would be included or excluded and the potential implications of that decision. Would a transgender male with a child and a career be included? Would you exclude non-binary individuals with children and careers?

(Rosen, 2022)

Considerations for designing and selecting research designs

Attrition in research

Attrition is defined as the loss of study participants over time (APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.). Attrition poses a significant risk to psychological research, primary research, longitudinal in nature, but also clinical research, like RCTs. Additionally, attrition also poses a significant problem to clinical practice, where the majority of participants are not completing enough sessions to experience the desired effect of interventions. Many evidence-based interventions generally 13-18 sessions for 50% of people to experience the desired effects, yet naturalistic data reveal that the average number of sessions attended is only 5, meaning the vast majority do not experience the intended effects (Hansen et al., 2002). Participant dropout poses a threat to both the internal and external validity of the research.

Why do participants drop out of research, and/or clients drop out of therapy?

Reasons for client drop out can typically be explained by one of the following variables: Client variables, therapist variables, or client-therapist variables. Client variables include things like low socioeconomic status (SES), criminal behaviour, severe psychiatric disorders, etc. Therapist variables include factors like being inexperienced and being perceived as hostile and unsympathetic. Lastly, client-therapist variables include having an inflexible, unaccommodating, unsupportive, and invalidating environment (Roos & Werbart, 2013).

Additionally, some treatments cause clients significant amounts of distress. Consider the treatment of OCD. To effectively treat OCD, clients must continuously expose themselves to their most severe triggers while simultaneously refraining from any compulsions which may provide them relief. While the treatment is effective, it is also very distressing, which can lead to client dropout (Hezel & Simpson, 2019).

As previously mentioned, RCTs use manualized treatments to ensure that everyone receives the same treatment in the same way, which improves internal validity. Conversely, while improving internal validity, manualized treatments threaten external validity by not considering real-world factors affecting attrition. In regular psychotherapy, the dropout rate is estimated to be around 30-50% (Roos & Werbart, 2013).

When conducting research on the effectiveness of treatments, generalizability should be a major consideration. Consider the effects of determining the effectiveness of a treatment based on a standard number of sessions when, in reality, only about half the people will follow through. While RCTs uphold a strict protocol designed to maximize internal validity, they still must consider external validity in order to be clinically useful.

Moving Research into Practice

The integration of empirical knowledge in everyday clinical work ensures that clients are treated with the best available knowledge, enhancing both the efficacy and ethical responsibility of the profession. As we have previously mentioned, evidence-based practice involves integrating the best available and supported knowledge to inform clinical decision-making tailored to the specific characteristics of the client. This model ensures that interventions are not only scientifically sound but also tailored to the unique needs and values of the client. The continued dynamic relationship between research and practice ensures that clinical practice remains adaptable and that research remains grounded in the realities of real-world current therapy. A potential problem in this scenario is that researchers may fail to communicate their findings to those who do not conduct research. This is why collaboration between researchers and clinicians enhances the external validity of research findings, thereby improving their relevance across different settings and client groups; however, the effectiveness of this dynamic relationship depends on whether the results can be reproduced, a concern that has become increasingly evident in multiple scientific disciplines.

A growing concern within psychology, the replication crisis refers to the widespread failure to replicate the results of previously published studies, including those that inform clinical practice, raising concerns about the accuracy and generalizability of the findings. This crisis challenges not only the confidence that clinicians place in evidence-based treatments but could also impact the public’s trust in psychological science (Rutjens et al., 2017). This crisis highlights the importance of open science and clear methodologies, as well as the use of well-supported findings in clinical settings to prevent ongoing errors in replication and the mistreatment of clients.

Researchers and clinicians continue to acknowledge gaps in delivering evidence-based treatments in clinical settings, including, but not limited to, organizational and leadership support, access to and support for competency-based training, and limited time and resources for training (Society of Clinical Psychology, n.d.). As a result, the field of implementation science has emerged to address these issues. While dissemination refers to distributing knowledge, tools, or practices to specific groups using various methods, such as manuals and presentations, there has recently been a shift towards implementation. Implementation refers to the integration of evidence-based practices into real-world settings to ensure their consistent and sustained use. For example, in clinical psychology, implementation science might be applied to support the routine use of an evidence-based therapy (such as CBT) in community health clinics by training clinicians, adapting workflows, and ensuring ongoing training and support.

Making Sense of the Results

Once a study has been conducted and the data are collected, the researcher must conduct data analysis and determine the extent to which their research hypothesis has been supported, as well as how the study’s results apply to society, a specific group, or clinical settings. Many psychological measures lack a direct correspondence between a specific score on a measure and a corresponding real-world experience. This is where statistical and clinical significance comes in. Statistical significance tells us whether a treatment or intervention had an effect that was unlikely to occur by chance. In addition to statistical significance, clinical significance informs the researcher and clinician that the difference is of a level that affects an intended area of a person’s daily functioning. For example, suppose you are conducting a study to test a new therapy for reducing PTSD symptoms, which is measured using a 50-point scale. If the treatment group experiences a 4-point reduction in PTSD scores compared to the control group, that reduction could be statistically significant. That does not mean that 4 points will show a noticeable or meaningful change in the person’s daily functioning. Therefore, from a clinical perspective, this improvement, while statistically significant, is too small to justify changing a person’s treatment plan. While statistical significance can be determined using tests that yield a p-value below a specified cutoff, clinical significance can be assessed in several ways. One example is to consider whether the participant returns to meaningful engagement in daily activities, school, or work.

Research Dissemination

The synthesis of research using systematic reviews and meta-analysis is crucial for implementing evidence-based practice. However, a problem that has been evident in academia for many years is the issue of who reads or has access to the results. The cost of accessing a single APA journal article is approximately $25 Canadian and having a subscription to a journal such as Canadian Psychology costs approximately $170 Canadian per year (APA, 2024; APA, 2025, respectively). The pay-for-access model creates inequalities in access to information, especially for those from lower-income backgrounds and researchers in developing countries (Open Universal Science, 2024). So, how can we address this problem? An increasingly popular trend among researchers is the adoption of open science. Open science is defined as methods and tools that promote transparency, accessibility, and reproducibility, thereby reducing barriers to knowledge sharing and enhancing research integrity.

An example of this is the textbook you are reading today, which is available on an Open Science Format platform, allowing anyone to access it free of charge. Open science can involve making research results, data, and articles freely available, which helps practitioners access research without paywalls, thereby further improving evidence-based practice. Researchers can also preregister a study to prevent unethical practice such as selective reporting and HARKing. Different platforms have also created badge that researchers can add to their publications if open science methods are used, examples of which can be seen in figure 3. Overall, ensuring that treatment providers have access to synthesized, high-quality, and freely available data bridges the gap between research and practice, further ensuring that clients receive the best possible care.

Summary/Conclusions

No one single study can change the world, nor answer all the questions. Each study, complete with its own limitations, confounds, and biases, still contributes to the scientific knowledge base on which the entire discipline of clinical psychology relies. A good scientist practitioner can critically evaluate evidence and thoughtfully apply it in practice. Moreover, clinical psychology research not only advances our knowledge but can also lead to improved treatment outcomes, help bridge the gap between theory and practice, and lead to systematic change through policy and advocacy efforts. Throughout this chapter, you explored the key areas that clinical psychologists research, the ethical considerations that apply to research, and the diverse methodologies to explore these psychological phenomena. These approaches not only included westernized methods to clinical research, but also other ways of knowing, such as two-eyed seeing. The research designs covered ranged from a single case to an extensive randomized control trial, each with its strengths and limitations to internal and external validity. The chapter also addressed how research findings are interpreted in both statistical and clinical contexts, emphasizing the importance of meaningful outcomes for real-world practice. We also discussed how large amounts of research are disseminated globally through systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and how our profession needs to integrate research into everyday practice —a process supported by ethical guidelines, evidence-based approaches, and open science initiatives.

Test yourself!

Media Attributions

- the scientific method © Robson Underwood is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- research in clinical psychology © Robson Underwood

- Albino pet rat © Xioyux is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- internal validity © Robson M. Underwood is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- RCT © Robson M. Underwood is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Representative Population © Robson M. Underwood is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- open science badges

A formal statement predicting the relationship between variables, which is tested through empirical investigation.

The integration of empirical and available research evidence to inform the clinical decision-making process across all stages of treatment in a manner that is responsive to the client's characteristics, culture and preferences.

The process of sharing information with patients that is essential to their ability to make rational choices among multiple options (Beahrs & Gutheil, 2001)

The ethical and legal obligation of psychologists is to protect clients' private information and only disclose it with informed consent or under specific circumstances required by law.

A person confined to a jail or prison.

This term makes no claim about guilt or innocence (contrary to words like “convict”), nor does it attach a permanent identity to an often-temporary status (such as “prisoner” etc.) (Cerda-Jara et al., 2019).

The intentional withholding of information or providing of false information to participants in order to prevent bias or influence on their behavior during a study.

A type of research design that involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event, illustrating a new or rare observation or treatment innovation.

An unaccounted-for third variable that influences both the independent and dependent variables in a study, which could distort the interpretations of results.

A non-experimental research design that measures and assesses the relationship among variables without manipulating them.

The rate of occurrence of new cases of a given event or condition (e.g., a disorder, disease, symptom, or injury) in a particular population in a given period. (APA, 2018)

The total number or percentage of cases (e.g., of a disease or disorder) existing in a population, either at a given point in time or during a specified period. (APA, 2018)

A statistical procedure that identifies underlying dimensions (factors) in a set of variables, test items or measures.

A type of research design that involves some form of manipulation by the researcher, examining the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable without randomly assigning participants to conditions or groups.

The variable that a researcher changes or manipulates to observe an impact on another variable. It is not affected by other variables being measured.

This is the measured variable that changes as a result of other variables.

A method of allocating participants to different groups based on chance.

A type of experimental research design that involves testing the effectiveness of interventions, treatments, or therapies in which participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more conditions.

A psychological and physiological response in which a person experiences improvement in symptoms after receiving an inactive or non-specific treatment, due to their belief that they are receiving a real intervention.

A type of research design that is used to assess the effectiveness of a psychological service, program, or intervention, involving data collection on aspects of current clinical practice.

A structured and comprehensive synthesis of multiple research studies on a particular treatment or issue aimed at determining the findings of all relevant evidence.

A process of statistically combining the quantitative results of research studies in a specific area to determine the overall effect.

A quantitative measure of the magnitude of a relationship.

The degree to which a study or experiment is free from flaws in its internal structure and its results can therefore be taken to represent the true nature of the phenomenon (APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.)

The extent to which the results of research or testing can be generalized beyond the sample that generated them. (APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.)

A subset of individuals, items, or observations selected from a larger population.

A sample which shares the essential characteristics of the population from which it was drawn (Gorvine et al., 2017).

The loss of study participants over time (APA Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.)

This refers to the widespread failure to replicate the results of previously published studies, including those that inform clinical practice, raising concerns about the accuracy and generalizability of the findings.

Distributing knowledge, tools, or practices to specific groups using various methods, such as manuals and presentations.

The integration of evidence-based practices or innovations into specific settings to facilitate routine use.

A type of significance that tells us whether a treatment or intervention had an effect that was unlikely to occur by chance.

A type of significance that informs the researcher and clinician that the difference is of a level that affects an intended area of a person's daily functioning.

Methods and tools that promote transparency, accessibility, and reproducibility, thereby reducing barriers to knowledge sharing and enhancing research integrity.

The unethical process of creating a hypothesis after the results are already known.