5 Intelligence and Cognitive Testing

Julia Byron and Dr. Laura Lambe

Case Study: John – Life After a Brain Injury

John is a 42-year-old man who worked as a construction manager. He was known for being good at solving problems, staying organized, and remembering lots of details on the job. Everything changed after he was in a serious car accident and suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI). After the accident, John noticed it was much harder to think clearly. He forgot things easily, got confused during conversations, and had trouble finishing tasks. He also became frustrated more often and felt like he wasn’t himself anymore.

John’s doctor referred him to a psychologist, who conducted a neuropsychological assessment (including intelligence and memory tests) to understand how his brain was working. One of the tests used was the WAIS-V (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fifth Edition). The test showed that John’s memory, processing speed, and problem-solving skills were below average. However, he still did well on verbal tasks, like understanding stories and vocabulary. These results helped John get the right kind of support. He started working with an occupational therapist to improve his memory and problem-solving skills. At work, he moved to a less stressful role and used tools like checklists and reminders to stay on track.

John’s story shows how intelligence testing can help health care professionals understand what kind of support someone needs after a brain injury. It also reminds us that intelligence is not just one number—it includes many different abilities that can change over time.

Now that you have learned about John you have a bit of an idea of what cognitive testing is and how it is a helpful in the clinical practice. The following chapter will cover more about what intelligence testing is, various types of cognitive and intelligence testing, and much more! This chapter focuses on intelligence testing as an example of cognitive testing. In practice, psychologists use many different cognitive tests to examine various thinking skills, including things like academic achievement, executive function, and phonological processing. We have chosen to focus on intelligence testing because it is one of the most common (and controversial) cognitive tests. Throughout the chapter, we will revisit John’s case to learn more about cognitive testing, with a focus on intelligence.

By the end of this chapter you will be able to :

- Understand what intelligence is.

- Compare and contrast theories of intelligence.

- Understand the different types and components of intelligence and cognitive tests.

- Describe why intelligence testing is needed in clinical practice and why it should be interpreted with caution.

What IS Intelligence Anyways?

We all know that “intelligence” means that you are smart – but what does that mean exactly? It is simply that you got straight-As on your report card? Or does it mean something broader, like being able to put together Ikea furniture, repair a car, or solve a tricky puzzle that’s been sitting on your coffee table for weeks? The truth is, intelligence can be all of these things: it is one’s capacity to learn from experience and adapt to the environment (Sternberg, 2012). Different theorists have different ideas as to how intelligence should be defined. Gottfredson (1997) proposed a broad definition, stating that intelligence involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience. Intelligence is a broad capability to understand our surroundings and figuring things out- rather than being solely test-taking abilities and ‘book-smarts’. It may come as a surprise that defining intelligence has been somewhat controversial in the field of psychology. As described below, many theories have been proposed to explain exactly what intelligence is.

Intelligence Myth Bust!

Myth: Having a larger brain means you are smarter.

Fact: Brain size does not strongly correlate with intelligence level. While some studies find a positive association between brain size and intelligence, this relationship is very weak (Pietschnig et al, 2015). It’s known that height is strongly correlated with brain size, and this factor is often overlooked in most studies looking at brain size and intelligence. So we know that intelligence is not directly related to the size of your brain, however brain activity in certain areas is linked with higher intelligence. Researchers have used brain imaging technology to observe brain activity when responding to various intelligence testing

Am I Born Smart?

As you will learn in the next section, some intelligence theorists believe that you are born with a fixed level of intelligence. While this perspective still exists today, research paints a much more nuanced picture. Studies have consistently shown intelligence in heritable, suggesting that genetic factors account for 50%-80% of the variation in intelligence (Plomin & Deary, 2015). Interestingly, this heritability increases with age, a phenomenon known as the Wilson effect (Bouchard, 2013). This is thought to occur because as adults, individuals increasingly shape their environments in ways that align with their genetic predispositions. But genes are not destiny! A large part of a person’s intelligence comes from their environment. Do your caregivers place high value in getting good grades? What is your socioeconomic status? Where do you live? All of these factors impact our intellectual development (Makharia et al., 2016). You can think of it like this: genetics set the range of your intellectual potential, but your environment determines where in that range you fall. Therefore, you are not simply born smart, you grow smart.

Great Minds Think Differently – Exploring Intelligence Theories

Spearman (1927)

Charles Spearman was one of the first psychologists to discuss intelligence. He stated that intelligence is based on a single factor, g, or general intelligence factor. This g is responsible for an individual’s performance on all mental ability tests (Spearman, 1927). In other words, having a higher amount of g meant you have higher intelligence, where having a low level of g indicated lower intelligence. Spearman also proposed the idea of s, or specific intelligence factors, which are responsible for abilities on specific tasks.

What are g and s?

Let’s break this down a little further. Spearman’s g would be a person’s general ability to perform well on math equations, logical puzzles, and learning new languages. An individual’s level of g allows them to perform well across a range of intellectual topics. Spearman’s s would be someone excelling specifically on complex algebra problems but struggling on memorization topics such as history. This individual would have a strong mathematical s factor which helps them perform well in math only.

Thurstone (1938)

Louis Leon Thurstone went further than Spearman and broke intelligence down into seven primary mental abilities: numerical facility, word fluency, verbal comprehension, perceptual speed, spatial visualization, reasoning, and memory (Thurstone, 1938). These seven abilities work together to complete tasks and understand the world around us. This was the first theory following Spearman’s that strayed away from the idea of g. In this theory, it was proposed that an individual may excel in one ability and struggle in another.

Cattell (1965)

Raymond Cattell proposed the idea of fluid intelligence and crystalized intelligence, both being subtypes of Spearman’s g (Cattell, 1965). Fluid intelligence is the ability to solve problems without using prior knowledge and a person’s ability to adapt to a new situation. This can be thought of as one’s innate intelligence potential. An example of this would be solving a new type of puzzle you have never seen before, identifying patterns in number sequences or shapes, or understanding abstract problems (Cattell, 1965). This would be knowing historical facts, the ability to write a research paper, or ace a math test. Crystalized intelligence is knowledge acquired across your lifespan whereas fluid intelligence not based on any previous knowledge (Cattell, 1965).

Gardner (1999)

Howard Gardner proposed a different theory of multiple intelligence where there are many categories and subcategories of intelligence, see Figure 1. Gardner breaks down intelligence from g to linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical , naturalistic, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal intelligence (Chen & Gardner, 2005). One critique of Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences is that it may better reflect talents rather than true intelligence (although both have value).

Test yourself!

Table 1: Descriptions and examples of each type of intelligence in Gardner’s theory of intelligence

| Type of intelligence | Description (Davis et al., n.d.) | Example |

| Linguistic | Ability to learn languages and use language correctly to create products (e.g. speeches) | Someone with high linguistic intelligence would be a poet |

| Logical-Mathematical | Ability to analyze problems and calculations | Someone with high logical-mathematical intelligence would be a mathematician |

| Spatial | The ability to think in 3D and visualize and manipulate images | A person with high spatial intelligence would be a pilot |

| Musical | The ability to produce, remember, and make meaning to musical patterns | Someone high in musical intelligence would be a song writer |

| Naturalist | Ability to distinguish and identify different kinds of nature such as animals and plants | Someone high in naturalist intelligence would be a farmer |

| Bodily-Kinesthetic | The ability to use your body to solve problems or create products (e.g., goals or movement) | Someone high in bodily-kinesthetic intelligence would be a dancer |

| Interpersonal | Ability to understand other intentions, motivations, and desires | Someone high in interpersonal intelligence would be a clinical psychologist |

| Intrapersonal | Ability to understand yourself and your own emotions, motivations, and desires | Someone high in intrapersonal intelligence would be a philosopher |

So… Which Theory is Right?

It is clear that over the years different psychologists have had different ideas as to what intelligence looks like. So who is right? The answer is… everyone! Intelligence can be thought of as a general concept, like Spearman’s g, and it is also specific skills, like Gardner’s theory. So, there is no one fully correct theory because intelligence can be thought of in many ways.

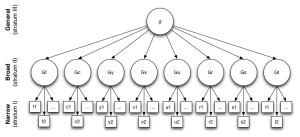

One last modern theory we will discuss is the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory of intelligence. This comprehensive model encompasses much of the historical work by breaking intelligence down into a hierarchical model. At the top of this hierarchy is general intelligence (g), followed by broad abilities (e.g., Gf fluid reasoning, Gc comprehension knowledge, etc.) and then is further broken down into narrow abilities (e.g., Gc includes abilities such as communication ability and lexical knowledge).

What makes the CHC model particularly robust is its strong psychometric support (McGrew, 2009). Factor-analytic studies consistently show that cognitive abilities cluster in ways that align with this model. In other words, this research shows that the different cognitive abilities are positively correlated with one another yet are distinct enough to warrant different factors. Modern intelligence tests, such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scales and the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities have been developed or revised to reflect this model, providing additional empirical validation through large-scale standardization samples (McGill et al., 2018).

Testing Your Brainpower: But What Are We Really Testing? There’s a Test For This?

Think back to our initial case study: After John’s accident, his doctor referred him to a psychologist to get some cognitive testing done, and one of these tests was something called the WAIS-V. This is one example of an intelligence test and would provide the psychologist with John’s intelligence quotient (IQ) score. This type of testing measures a person’s intellectual capacity, providing both an overall IQ score (like “g”) and domain-specific scores (like the broad and narrow abilities). After testing, the psychologist would compare John’s performance to the performance of same-aged peers.

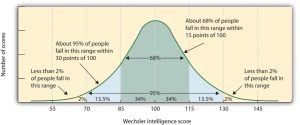

Let’s get in the math-mode for just a minute while we go over the scoring of IQ tests. Scores are standardized based on age, with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Thus, an IQ score of 100 is “average” regardless of whether the client is 16, 34, or 78 years old. If you have taken any type of Calculus or Statistics class, you may remember the term bell-curve or normal distribution. The normal distribution is a way of describing how certain measurements (like IQ, height, and weight) tend to be spread out in a population. Most people cluster around the middle (the average) with fewer people on either side.

Figure 2 shows that the scores are broken down in standard deviations of 15, and the bulk of scores (68%) fall within this “average” range. The blue section shows scores that are below average or above average- this is two standard deviations away from the mean in either direction (Walters, 2020). Finally, the yellow section on the end of the bell curve is rare; only 2% of people fall in this range on either side. This type of scoring allows psychologists to understand what is typical and might be considered unusually high or low, which can be informative for diagnostic decisions and informing recommendations.

So why is scoring so specific on intelligence tests? The scores are standardized, meaning that they’re carefully designed and tested on large groups of people to create a consistent way of interpreting results, creating what is known as normative data (or “norms”). This allows psychologists to compare an individual’s scores to their same-aged peers. In John’s case, his psychologist was able to see where his weaknesses fell in comparison to others his age, helping to guide a personalized treatment plan.

You may be thinking, “This sounds great! John was able to complete some tests and then get the help he needs to return back to work!”. And while that’s true in many cases, it is also important to recognize the problematic history behind these tests. The development of IQ tests has not always been fair or inclusive. In fact, the norms used to interpret scores were often based on samples that lacked racial, cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic diversity. So how did we get here? Let’s take a closer look at the origins of IQ testing and the biases built into early test development.

The Dark History of IQ Testing

Binet & Simon & Terman, Oh My

IQ testing is problematic for a number of reasons, one being the way it was created. In France in 1905, Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon created a test that was designed to separate the ‘normal’ children from the ‘mentally challenged’ children in schools (Kaufman & Harrison, 2008). This started the foundation for what is now known as IQ testing. Other researchers then hypothesized that certain cognitive abilities such as verbal reasoning, working memory, and visual-spatial skills reflected one’s general intelligence or g factor (Inan, 2020). Simon and Binet then developed a battery of tests for each of these cognitive abilities and combined them to get a single score (Inan, 2020).

Two years later in 1908, American Psychologist Henry Herbert Goddard caught wind of the Binet-Simon intelligence scale (Benjamin, 2009). He then translated the scale to English and published his version of the scale title “The Binet and Simon Tests of Intellectual Capacity”. Goddard was very eager to use his new scale and convinced American physicians to use his test in their practice (Benjamin, 2009). In 1914, he was using the tests as evidence in the court systems. Goddard believed that intelligence and “feeblemindedness” were hereditary, and advocated that society should keep feebleminded people from having children to eliminate it from the population (Benjamin, 2009). He went as far as to say that these individuals should undergo sexual sterilization, an inhumane surgery that leaves individuals unable to have children due to organ damage. Goddard is just one example of how society (and psychologists) placed too much value on intelligence, leading to drastic efforts to eliminate those with lower intelligence.

In 1916, psychologist Lewis M. Terman revised the Binet-Simon Scale, making it the Stanford-Binet Scale. Terman standardized the scale and introduced the term intelligence quotient (IQ), which was the person’s mental age (score from scale) divided by their chronological age, multiplied by 100 (Kaufman & Harrison, 2008). Since then, the Stanford-Binet Scale has been revised and re-standardized many times. This test is still used today, with the most recent version released in 2003 (Stanford-Binet 5th edition).

Army Alpha

During the first World War, the American government needed a way to quickly determine the strengths of army recruits. The government used the recently developed Binet-Simon scale to determine if soldiers were mentally capable to complete military activities (Lee & Hunsley, 2021). The government then turned to the recently developed American Psychological Association (APA), chaired by Robert Yerkes, to aid in separating these men based on their mental functioning. The APA developed a scale to measure soldiers verbal mental abilities, known as the Army Alpha test, and developed a test to measure non-verbal mental abilities called the Army Beta test (Lee & Hunsley, 2021). The Army Beta test was administered on individuals who could not read or write or had limited English language skills. To save time and expenses, these tests were administered in groups.

At this same time, the topic of eugenics was quite popular- the idea that society should control reproduction to eliminate “undesirable” traits and increase “desirable” ones. Within this framework, many people believed that intelligence was a heritable trait that we can control. These harmful beliefs were often tied to racist assumptions, including the idea that intelligence was linked to race. As a result, the military unjustifiably concluded that certain racial groups were intellectually superior to others.

This conclusion was deeply flawed, especially because the Binet-Simon scale was administered in English. Individuals whose first language was not English, often immigrants and racialized individuals, were at a disadvantage and tended to score lower. These lower scores were misinterpreted as evidence of lower intelligence, rather than a reflection of language and other systemic barriers within the test itself. Consequently, these biased results reinforced harmful stereotypes that White people were inherently the superior race when it came to intelligence.

The enduring myth that intelligence is biologically determined and racially linked has caused profound harm, shaped discriminatory policies and reinforced systemic racism. These misconceptions, rooted in pseudoscientific ideologies like eugenics, were legitimized through flawed testing practices and misinterpretations of data. The American Psychological Association issued a formal apology in 2021, acknowledging psychology’s role in promoting and perpetuating racism. The APA’s apology is a critical step toward accountability and healing. It calls on the field to confront this dark past, dismantle racist practices, and commit to culturally responsive research and practice. By acknowledging these harms, psychology can begin to rebuild trust and ensure that science services justice rather than prejudice.

IQ Testing Today: David Wechsler

Despite this dark history, intelligence testing remains widely used in clinical practice. One of the most common modern IQ tests are the Wechsler scales (think back to our case example, John). David Wechsler is a well-known name in the intelligence testing world having first created the Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale made for adults (Abramowitz et al., 2023). He wanted to create a test that assessed multiple types of intelligence. Previous tests focused mainly on verbal abilities, and while important Wechsler wanted to incorporate other abilities in his scales. Later Wechsler created both the Wechsler’s Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), as the names suggest one is an adult version and one is a child version (Abramowitz et al., 2023). The original scale was first developed in 1955. Different versions have been published over the years the WAIS-R (revised edition) in 1981, the WAIS-III in 1977, and the WAIS-IV in 2008. In 2024 the WAIS-V was released.

WAIS-V

The WAIS-V is described as one of the most comprehensive and reliable assessment tools for cognitive ability (Gunelson, 2024). This test can be administered to individuals ages 16-90 (Rodin, 2025). The WAIS-V is broken down into a five-factor model revealing index scores in the following areas: Verbal Comprehension, Visual Spatial, Fluid Reasoning, Working Memory, and Processing Speed . The Verbal Comprehension Index is the ability to accurately use words in the appropriate context and language-based reasoning. This would be a person’s ability to explain the meaning of “Don’t cry over spilled milk”. The Visual Spatial Index is the ability to perceive, analyze, and mentally manipulate visual patterns and spatial relationships. In the real world, this would be like building Ikea furniture by following a diagram. The Fluid Reasoning Index is the ability to logically solve problems on-the spot using reasoning to identify and apply rules to a context, without using past experiences. This would be like solving a riddle you have never heard before: “I speak without a mouth and hear without ears. I have no body, but I come alive with wind. What am I?”. Answer: an echo. The Working Memory Index is our mental capacity to hold and manipulate information for a short period of time. In the real world this would be like remembering a person’s phone number long enough to dial it. The Processing Speed Index is the ability to scan, understand, and respond to information quickly and accurately. This would like quickly spotting spelling errors while proofreading a paper. There are 10 core subtests in the WAIS-V used to assess these areas (see Table 2).

Table 2: Full list of WAIS-V subtests

| Primary Index Scale | |

| Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) |

|

| Visual Spatial Index (VSI) |

|

| Fluid Reasoning Index (FRI) |

|

| Working Memory Index (WMI) |

|

| Processing Speed Index (PSI) |

|

Test yourself!

WAIS-V Administrating Scales (Abramowitz et al., 2023; Lee & Hunsley, 2021)

| Name of Scale | About Scale | Example Question | Example Answer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vocabulary (VCI) | In this test the individual must give the examiner the definition to various words that increase in difficulty. This is believed to be the closest test of g. | Define the word benevolent. | Benevolent means to be kind or charitable. |

| Similarities (VCI) | This is where the individual must explain how two objects are similar. Examinee’s are required to think about the basic properties of an object and determine where similarities lie. | How are a pen and pencil similar? | They are both used to write. |

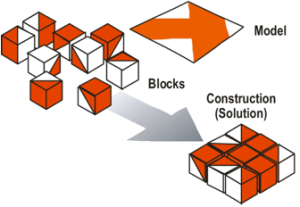

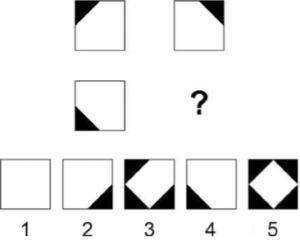

| Block Design (VSI) | The examinee is asked to use blocks to mimic a block pattern seen on a card. The tasks require turning a two-dimensional design into a three-dimensional design and tests visual motor coordination and analytic synthesizing ability. | Use the blocks to create a copy of the model example. From: (Miller et al., 2022)  |

|

| Visual Puzzle (VSI) | This involves the examinee to view a puzzle and choose which pieces go together to make the puzzle. They are presented with many options that make sense to fit in the puzzle, but they must choose the desired number of pieces needed to correctly complete the task. | Which of these three pieces go together to make the top example? You must choose three. From: (Buckley, 2023)  |

1, 2, and 6 |

| Matrix Reasoning (FRI) | Here the individual must correctly choose which image will be next in a visual sequence. They are presented a visual pattern and ask to pick the next image in the sequence from a series of options. This subtest measures visual information processing and abstract reasoning skills. | Choose the correct image that will complete the pattern. From: (Tranel et al., 2008)  |

Picture 2. |

| Figure Weights (FRI) | This tasks involves viewing two images. One has a balanced scale with complete objects on either side. The other has the balanced scale with only one side containing objects and the other with a question mark indicating the examinee must select which objects will keep the scale balanced. | Choose the correct objects to keep the scale balanced.  |

Two stars. |

| Digit Sequencing (WMI) | This task involves the examinee to say the digits back to the examiner in ascending order (lowest to highest). Again same as the previous two digit subtest the length of digits increases over time, and this is able to test individuals short term memory and attention. | Repeat this number sequence back to me in ascending order. 6,4,1, 9, 2. | 1, 2, 4, 6, 9. |

| Running Digits (WMI) | This subtest is also new to the WAIS-V. The examiner informs the examinee that they will read out a series of digits and they will be asked to recall a specific number of digits read in the order they were read. The examiner can stop reading digits at any time so the examinee must be constantly updating their working memory with new digit sequences. | I am going to read out a series of numbers. When I say stop you tell me the last four numbers I read in the same order I said them. 1, 4, 7, 3, 9, 1, 3, 6, 2, 4, 1. | 6, 2, 4, 1. |

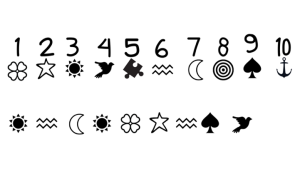

| Coding | In this subtest examinees are given a key that corresponds numbers to a symbol. They are tasked with correctly using the key to fill in the symbols that match the number sequence. They are asked to complete this as quickly as possible. | Use the key to correctly fill out the number sequence.  |

3, 6, 7, 3, 1, 2, 6, 9, 4. |

| Symbol Search | In this subtest the examinee is shown a target symbol and then told they must determine if this symbol appears in an arrange of different stimuli. They are then presented with multiple symbols that could include their target symbol. Examinee’s must check if their symbol is present in this arrangement. | Is the target symbol in the arrangement? |

No. |

John’s Score

Now that we have a better understanding of how intelligence tests are scored and understand the different categories of the WAIS-V lets break down John’s scores and see where he excelled or had some weaknesses.

| Index | Score | What does this mean |

| Verbal Comprehension Index | 92 | Average |

| Visual Spatial Index Score | 117 | High average |

| Fluid Reasoning Index Score | 84 | Low average |

| Working Memory Index Score | 78 | Low |

| Processing Speed Index Score | 64 | Very Low |

As you can see in John’s table score he excelled in questions in the Visual Spatial tasks, meaning his perceptual and visual-spatial reasoning abilities are an area of strength. His scores also indicate that he performed relatively well on Verbal Comprehension and Fluid Reasoning tests. Working Memory and Processing Speed, however, were areas of weakness, meaning he has trouble holding and manipulating information in his mind and likely struggles to complete tasks quickly, especially those that require focus and have multiple steps.

WISC-V

This is the child version of the WISC-V. This scale was first developed in 1949, a revised version (WISC-R) released in 1974, in 1991 the WISC-III was published, in 2003 the WISC-IV was released, and the fifth version was released in 2014. The WISC-V is used for children ages 6 to 17 years old. The recent version has been revised to provide a broader assessment of children’s cognitive abilities and often used in assessments querying intellectual disabilities and learning disorders in children.

The WISC-V is an age-appropriate tool that was adapted to provide children with simplified instructions, samples/practice items for each test, and updated the material to be more engaging to children (Lee & Hunsley, 2021). This version has the same five primary indices as the WAIS-V, Verbal Comprehension, Visual Spatial, Fluid Reasoning, Working Memory, and Processing Speed.

Other Types of Cognitive Testing

Remember that “cognition” refers to a host of thinking skills beyond intelligence, and includes abilities like memory, attention, executive functioning, and academic achievement. Thus, in clinical practice, psychologists typically employ a battery of other cognitive tests in addition to an IQ test. There are hundreds (if not thousands) of different cognitive tests available to psychologists. A few other commonly used tests are described below:

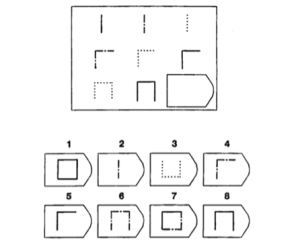

Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices Test

The Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices scale was created by John Raven and published in 1938 (Bilker et al., 2012). This is a non-verbal intelligence test that uses multiple-choice questions to measure abstract reasoning. This is a 60 multiple-choice question test in which the test-taker has to use pattern recognition to identify a missing part of a design (see Fig. 5). The test has been proven to be a reliable tool to measure intelligence (Bilker et al., 2012). Raven also developed 36 other items, making a new scale title Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices Test, as well as a coloured version being The Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices Test (Raven, 2000).

Think like a psychologist:

Why would it be helpful to have an IQ test that is not reliant on language skills?

Example Question:

Identify the piece required to complete the design from the options below.

Correct answer: 6

Wechsler Memory Scale- Fourth Edition

This scale was originally published in 1945, then revised in 1987 and 1997. The fourth edition was published in 2009 (Pearson, 2009) . This test can be administered to individuals between the ages of 16 and 90 and is typically paired with the WAIS-V (Pearson, 2009). To understand this scale let’s do a bit of PSYCH 100 review on memory.

Memory 101

Procedural memory a type of long-term memory involving remembering how to do things (“muscle memory”). This memory is used to complete activities without much thought, such as brushing your teeth. In contrast, declarative memory is the conscious recollection of facts or events. Declarative memory is also broken down into semantic and episodic memory. Semantic memory is your knowledge on general facts (e.g., what is the boiling temperature of water?). Episodic memory deals with the person’s direct experiences, such as what did you have for dinner last night (Lichtenberger et al. (2001)).

The WMS-IV deals specifically with a person’s episodic memory. Psychologists cannot simply ask about a client’s life because it’s difficult to know if the information is true or not. Instead, psychologists use auditory and visual tasks that tests a person’s episodic memory for novel information that has a “correct” answer. For example, one such task would involve presenting the client with a design (e.g., dots on a grid) and then removing the visual aid and asking them to remake the design correctly. This test is commonly used on clients presenting with a brain injury (like John), or a brain dysfunction such as dementia, epilepsy, or Parkinson’s disease.

Wechsler Individual Achievement Test- Fourth Edition

This test was originally published in 1992 and then revised in 2002. The Canadian version was released in 2003 (WIAT-III) and in 2024 the WIAT-IV was released. This test can be administered to individuals between the ages of 4 and 51 and tests a person’s academic achievement and problem-solving skills. Essentially, this is like a typical school test, as it primarily covers skills in reading, writing, and mathematics. This test is commonly used in conjunction with the WISC, which together provide information relevant for a diagnosis of a learning disability.

Beyond the Score: How Clinicians Make Sense of Intelligence and Cognitive Tests

Hopefully, now you have a pretty good idea of what intelligence and cognitive testing is. But you may still be wondering how it is used in the real world. We learned about John but how else are these tests useful? To answer this question we are going to hear from Dr. Erica Baker.

Psychologist Spotlight: Dr. Erica Baker, R. Psych.

Psychologist Spotlight: Dr. Erica Baker, R. Psych.

Hi there, my name is Erica Baker. I am a registered clinical psychologist. I obtained my doctoral degree in Clinical Psychology from McGill University and completed my residency at the Hospital for Sick Children. Following completion of my degree I moved back to Nova Scotia and took over my mother’s private practice in psychology. I am presently the owner of Erica Baker Psychological Services (EBPS), a private practice specializing in the psychological assessment of children, youth and adults. EBPS has more than 20 psychologists who are working in the practice as independent contractors. Approximately half of the psychologists are working full time and half are working part time. Many of the part-time psychologists have young families or are also working in public settings (e.g., schools, hospitals) part-time. About half of my work is directly with clients, and half of my work is administrative, running the business and training psychologists in the practice.

Conclusion

In this chapter, you learned about the history of intelligence tests (the good and bad), different intelligence theories, types of intelligence and cognitive tests, and how these tests are used in clinical practice.

Do the pros outweigh the cons? We know intelligence testing can be very helpful, but if used incorrectly it can be very harmful. This is why cognitive testing requires advanced training, often specific to clinical psychologists.

Test yourself!

Media Attributions

- Computed_tomography_of_human_brain_-_large © Department of Radiology, Uppsala University Hospital. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- gardner © Julia Byron is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Carroll_three_stratum_model_of_human_Intelligence © Tim Bates is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- normal distribution

- American soldiers taking a predecessor of the Army Alpha – November 1917 © U.S. War Department, November 1917. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dr.David Wechsler © New York University. School of Medicine is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Blockdesign

- visual puzzle

- matrixreasoning

- figure weights

- coding

- symbol search

- raven

- ericabaker

The capacity to reason and solve novel problems independently of previously acquired knowledge, relying on abstract thinking, pattern recognition, and logical inference. It reflects an individual’s ability to adapt to new situations and process information flexibly.

Knowledge acquired across your lifespan (e.g., knowing history facts or the ability to write a research paper).

A widely accepted framework of cognitive abilities that combines Cattell and Horn's fluid and crystallized intelligence theory with Carroll's three-stratum model, organizing intelligence into broad and narrow abilities.

A numerical score derived from standardized tests designed to measure intelligence relative to a population average of 100.

The process of designing and testing assessments on large, representative groups to create normative data, allowing psychologists to interpret scores consistently and compare an individual’s performance to that of their same-aged peers.

The ability to accurately use words in the appropriate context and engage in language-based reasoning, such as explaining the meaning of common expressions.

The ability to perceive, analyze, and mentally manipulate visual patterns and spatial relationships, such as following diagrams to assemble furniture.

The capacity to solve novel problems using logic and reasoning to identify and apply rules without relying on prior experience, like solving an unfamiliar riddle.

The mental ability to temporarily hold and manipulate information, such as remembering a phone number just long enough to dial it.

The ability to quickly scan, interpret, and respond to information with accuracy, such as rapidly identifying spelling errors while proofreading.

A nonverbal test of abstract reasoning that measures a person’s ability to identify patterns and relationships in visual information, often used to estimate fluid intelligence without relying on language skills.

The ability to recall novel events or information, measured through auditory and visual tasks with correct answers, used to assess memory in individuals with brain injuries or neurological conditions.