9 Cognitive Interventions (CBT)

Yanna Kachafanas and Dr. Margo C. Watt

Say you have been struggling with your mental health, and you decide that it is time to reach out to a professional for support. You might be overwhelmed to hear about the many different potential treatment options that are available. Depending on what challenges you are facing, you will likely be presented with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as a promising route for treatment. As one of the most common and empirically supported forms of therapy, CBT emphasizes the connection between our thoughts and our behaviours. This chapter will provide a brief introduction to CBT as well as a general overview of its applications.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the cognitive model and relationships between cognitions, emotions, and behaviours.

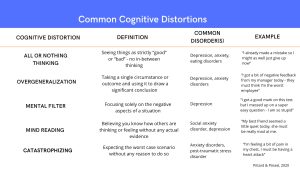

- Identify common cognitive distortions that can lead to maladaptive behaviour.

- Describe the process of CBT, including commonly used CBT techniques and applications to various DSM-5 disorders.

- Evaluate the strengths and limitations of CBT.

What is CBT?

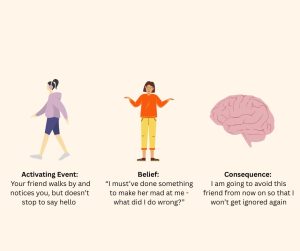

CBT’s beginnings can be traced back to the 1950s and Dr. Albert Ellis who developed the earliest form of cognitive therapy – rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT). This development involved a model known as ABC – an acronym for Activating events, Beliefs, and Consequences. Using the ABC model, the client is encouraged to think about both their rational beliefs (rooted in logic with consideration of the facts of a given situation) and irrational beliefs (rooted in emotion rather than fact) and how these beliefs impact their approach to everyday situations. For example, you make a small mistake at work about which you feel bad. Feeling bad could activate a potentially irrational thought process whereby you come to believe that your boss thinks you are totally incompetent and needs to be fired. On the other hand, a rational thought process would allow you to understand that mistakes happen and can provide valuable lessons.

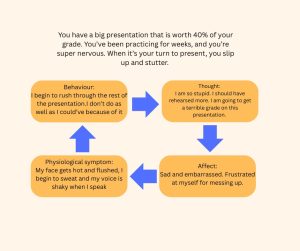

Cognitive therapy evolved in the 1960s with Dr. Aaron Beck. While working with his clients, Beck found that the predominant psychological theory of behaviourism couldn’t adequately explain what he was seeing in his practice. According to this theory, people’s behaviour could be explained by conditioned associations (e.g., dog bite = fear of dogs) and reinforcement (e.g., earning rewards for being good, losing rewards for being bad). Behaviourism drew conclusions based on observable behaviour without consideration of cognitive processes. Beck, however, found that his clients’ feelings were directly connected to their ways of thinking, which often consisted of negative perceptions of self, the world, and the future (now known as the cognitive triad). Beck discovered that by working with his clients to uncover their negative automatic thoughts (i.e. pessimistic, irrational thoughts that can be triggered by stressful situations), they were able to identify distorted or illogical ways of thinking and then restructure them into more adaptive thinking patterns. For example, someone struggling with negative automatic thoughts may believe that if they stutter while giving their presentation, they are a failure. After working with their therapist to identify and challenge this thought, they remind themselves that one stutter will not make or break the presentation.

Today’s CBT is a combination of cognitive therapy (based on the work of Ellis and especially Beck) and behaviour therapy, which uses techniques derived from behaviourism. CBT is a form of psychotherapy that is used to target dysfunctional/harmful patterns of cognitions (thoughts) that can influence emotions (feelings or affect) and behaviour. It involves changes in ways of thinking and ways of behaving by utilizing short-term, structured, present-oriented sessions. Outside of these sessions, CBT requires clients to complete “homework” assignments, which include actively practicing the skills that they are learning. Actively engaging with the skills is intended to strengthen the therapeutic effects. Homework has a range of benefits, such as reinforcing concepts, applying skills to real-life scenarios, trying out solutions, as well as allowing the client to see what is working and/or not working for them, where they might need more support and guidance from their therapist (Dozois, 2010). Today, cognitive therapy has been applied to a wide range of mental health disorders, including anxiety disorders, depression, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. CBT is the most empirically supported psychological intervention, used in over 130 countries, implemented in both face-to-face therapy sessions and through online sessions.

Test yourself!

The Cognitive Model & The ABC Model of Behaviour

As mentioned earlier, CBT involves noticing and understanding how your cognitions and behaviours are connected, and how they affect your mental health. The cognitive model framework suggests that dysfunctional thinking patterns are present (and common) in all psychological disorders. The key to improvement in these disorders is to recognize and re-evaluate these thoughts. To do this effectively, clients should evaluate not only their thoughts, but their deeper-rooted beliefs (Beck, 2011).

Various models have been developed to illustrate this process, one of which is Ellis’ ABC model. The ABC model emphasizes the role of a person’s perceptions of a situation. For example, different people may experience the exact same situation but have very different reactions. First, information is gathered from the general environment, which allows us to form a perception of the event. This perception is what elicits our emotional reaction, not the event itself (Ellis, 2001).

This model is particularly interested in automatic thoughts – quick evaluating thoughts about what is happening around us. These thoughts tend to stem from our beliefs, which are fundamental understandings about ourselves and the world around us. These beliefs then shape the formation of attitudes, assumptions, and rules (Ellis, 2001). Negative automatic thoughts are a common initial reaction to stressful life events and are experienced by everyone. Although normal in some capacity, it is important to distinguish between common occurrence of these thoughts and when they gain the potential to be harmful.

The image above shows an example of Ellis’ ABC model. It begins with some sort of activating event – this can be any event that someone experiences that prompts an emotional response. Following the event, the person forms a belief. These beliefs are often based on pre-existing schemas that they have developed through past experiences and knowledge about how things have occurred in the past. The final step is the consequence, or the outcome. Given that everyone has their own unique schemas and beliefs, people will experience these consequences differently.

Other models have highlighted the reciprocal relationship between emotions, behaviours, and thoughts. When you find yourself in a situation that may be stressful or uncomfortable, you often begin to form negative thoughts. These thoughts will then prompt a corresponding affect, which may then activate some physiological symptoms such as sweating or shortness of breath. Finally, once you begin to experience these physiological symptoms, you may adjust your behaviours in ways that align with the effects and symptoms that you are experiencing. This tends to be a cyclical process, as your behaviours may then begin to influence the way you think about yourself and the present situation. This is shown in the image above.

CBT Techniques

During the first CBT therapy session, a thorough assessment is conducted to gain a full understanding of the client’s needs. The therapist takes note of how the client is feeling and in what areas they may need guidance. Results of the assessment guide the therapist in determining what is the best approach to treatment (psychotherapy, medication, etc.) and allow for tracking the client’s progress to ensure that the treatment is working effectively.

An important aspect of all therapies is developing the therapeutic relationship. This is the process of building trust and rapport between the therapist and the client in order to facilitate open communication. The development of the therapeutic relationship begins at the first encounter and evolves through the informed consent and assessment process. Establishing a healthy therapist-client relationship may take a number of sessions, depending on the client. Important tools for establishing this relationship include good counselling skills and collaborative empiricism. Good counselling skills involve friendly demeanour and body language; active listening; use of empathetic statements and probing questions to prompt a deeper understanding of the client’s thoughts and feelings. Collaborative empiricism is a treatment strategy that involves the therapist and client working together to develop the treatment plan, making adjustments together as necessary (Beck, 2011). Collaborative empiricism acknowledges that different methods work for different clients, while also empowering clients to play an active role in their treatment and actively participate in their “homework.”

CBT involves a number of components designed to target maladaptive cognitive and behavioural patterns. This chapter focuses on the components of psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and behavioural interventions. Behavioural interventions are also used as standalone treatments and will be discussed in further detail in a later chapter. Psychoeducation involves teaching the client about their diagnosis, its typical treatment, and what they can expect from their participation in CBT. This provides a roadmap for treatment by explaining the client’s diagnosis and symptoms, as well as exploring the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviours with the client.

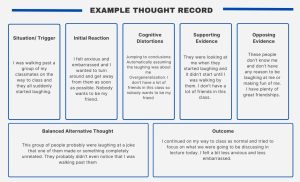

Psychoeducation encourages adherence to treatment plans and promotes better outcomes. Cognitive restructuring is an exercise in which the therapist guides the client through a series of open-ended questions. In this, unhelpful thoughts are identified and challenged. Clients are encouraged to consider what these thoughts mean and why they hold such importance. This method helps to get to the deepest meaning of the thought so they can begin to change their way of thinking. Behavioural interventions are active strategies that are used to modify clients’ behaviours and thoughts by having them directly challenge their beliefs (e.g., exposure therapy). Behavioural interventions are also used as standalone treatments and will be discussed in further detail in a later chapter

Another common aspect of CBT is preventing relapse (i.e. the return of symptoms and maladaptive behaviours after they have been absent for a period of time). Many CBT approaches include pre-practiced strategies that clients can draw upon to mitigate the risk of relapse occurring. These strategies vary depending on the type of disorder, but some common examples include reviewing coping strategies, anticipating areas that may be a cause of concern, and identifying triggers (Watt & Stewart, 2008). Some of these triggers include stressful or adverse life events, social pressures, negative physical or mental health states, and persistent negative thinking patterns.

One prevention model was developed by Alan Marlatt (1985). This model suggests that the risk for relapse increases based on two factors – high-risk situations and a person’s lack of confidence or ability to cope with these high-risk situations. A hopeful aspect of this model is that clients generally have multiple opportunities to work on these skills. Lapses in behaviours (slipping back into maladaptive behaviours for a shorter period of time) are considered a normal part of the therapeutic process and give clients a chance to learn about what relapse might look like for them. This could be identifying situations that could be particularly triggering to the individual client, knowing the warning signs that may pop up in a risky situation (e.g. what being triggered might feel like to the client), and how they may react to a certain situation. This learning process allows clients to adapt and be more prepared for such situations in the future (Larimer et al., 1999).

CBT Applications

CBT has demonstrated its effectiveness in reducing distress, enhancing the functioning and well-being of clients with a wide range of psychological disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression) and physical disorders (e.g., chronic pain). It is the most widely used psychological intervention for both anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. This broad application has been supported by extensive research. A lot of this research is conducted via randomized controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs are used to determine if a clinical intervention is beneficial under a wide range of circumstances and for a wide range of participants. This is often done by randomly assigning participants to one of various treatment groups (medication, placebo, CBT, etc.) and seeing what kind of treatment provides the best outcome (David et al., 2018).

To get an idea of what CBT is like in practice, it can be valuable to see how it might be applied to different disorders. Two common disorders are generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder.

CBT for generalized anxiety disorder involves clients learning cognitive skills to help restructure maladaptive ways of thinking and behavioural skills, such as relaxation techniques and problem-solving skills. CBT for GAD also includes behavioural modification by teaching clients how to cope with and manage their anxiety, rather than engaging in avoidance behaviours, which will actually worsen symptoms. For other anxiety disorders such as social anxiety disorder and panic attacks, it is common for clients to do exposure therapy paired with cognitive therapy for catastrophic thinking and other cognitive distortions (Lang, 2004)

The use of CBT for depression has been supported in a large number of studies. CBT has been found to be just as useful as antidepressants for patients with mild to severe depression (Vasile, 2020), as well as leading to lower relapse rates compared to the use of solely antidepressants (Manaswi et al., 2020). Paired with behavioural components such as behavioural activation (i.e., engaging in healthy behaviours to generate positive moods) and social skills training, cognitive therapy targets common cognitive distortions, building a more positive self-image by practicing self-acceptance, and learning how to cope with life stressors.

Depression and anxiety disorders are just two examples of many that show how beneficial CBT can be. In a review of meta-analyses, CBT was shown to be an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder (Butler et al., 2006). It has also been used in the treatment of other psychological disorders, such as managing negative body image in those with eating disorders, and through exposure therapy in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (Society of Clinical Psychology, 2022). Further, components of CBT have also been used in the treatment of chronic physical illnesses such as diabetes and headaches (Society of Clinical Psychology, 2022).

As mentioned earlier, a strength of CBT is that it can also be used for various patients across the lifespan. For example, CBT can be adapted to be beneficial for young children by using simpler phrasing of emotions and by adding more visual representations to the treatment. Lots of times these treatments include incorporating playing games as a way to demonstrate key concepts and to make potentially uncomfortable behavioural tasks less intimidating (Graham & Reynolds, 2013). More recently, there has been work done to make cultural adaptations to CBT. These adaptations could be making an effort to recognize and acknowledge cross-cultural differences in expressions of mental disorders and using inclusive language. One systematic review found that methods such as using culturally familiar relaxation techniques, defining healing in cultural relevant ways, as well as recruiting mental health professionals who were culturally competent or of similar cultural background, were all beneficial in increasing the effectiveness of CBT in culturally diverse populations (Menon et al., 2024).

Evaluation of CBT

As we have discussed, CBT is an effective form of therapy for a variety of mental health disorders and can be adapted to be beneficial for various clients. It is a strong form of treatment because we know it is effective – it is the most empirically supported psychological intervention across different mental health disorders and is the primary form of training in many clinical psychology programs. In fact, a lot of research has supported the idea that CBT is just as effective as medication for the treatment of many disorders and leads to lower dropout rates (Petruzzi, 2023). While still somewhat in the early stages, online administration of CBT is on the rise, which could potentially help mitigate some of the barriers to CBT accessibility, such as cost concerns, long waits for available appointments, and geographical location (Kumar et al., 2017).

Despite all its strengths, CBT has some limitations that are important to consider. For one, CBT was predominantly developed by white male psychologists originating from WEIRD countries, meaning it lacks a multicultural perspective. Moreover, most of the research looking at CBT has been conducted with white middle-class populations, making it hard to generalize results to populations beyond this. Further, CBT requires that the client makes a consistent and genuine effort to improve upon and build skills. It is not enough for a client to simply show up for their sessions – they have to be actively collaborating with their therapist and working on the skills both during and outside of the sessions. If a client is unwilling or unable to complete their “homework”, it can make it difficult to gain all the benefits of the treatment.

Innovative Uses of CBT – Linnaranta et al., 2024

Across Canada, access to mental health services has been limited due to long wait times and lack of availability of healthcare providers. For the Inuit community of Nunavik, Quebec, this gap in mental health care is especially prominent. While accessible by flight, medical services are predominantly located in Montreal. Further, when professionals have been available in Nunavik, the providers do not speak the first language of the community, Inuktitut. To help bridge this gap, a project was developed working with members of the community to design a virtual reality CBT treatment manual and virtual reality environments that help minimize the effects of a more distant geographical location, as well as the lack of availability of mental health professionals, specifically those with cultural competency.

This VR-CBT has been culturally adapted to be effective for the members of the Nunavik community. This cultural adaptation included rejecting some traditional CBT techniques and adding some new techniques, such as emotion management and individual empowerment. Further, stress inoculation training was introduced, and VR was used to practice the new skills in session. The program was also developed around the understanding that the Inuit are facing legitimate systematic adversaries and included culture-specific activities as a crucial component of the therapy.

CBT has been used to target anxiety sensitivity (AS or “fear of fear”, Reiss & McNally, 1985). AS is a known transdiagnostic risk factor for a range of psychological and physical disorders. Transdiagnostic means that AS is a risk factor shared by these disorders. Individuals with high levels of AS fear the physiological sensations associated with anxiety (e.g., dizziness, shortness of breath, racing heartbeat, etc.). This fear is based on maladaptive beliefs that these sensations will lead to harmful social, psychological, and/or physical consequences (Stewart, 2024).

Below is an example case study that has been adapted from Watt and Stewart’s Overcoming the Fear of Fear (2008) that describes an example of a CBT approach to treating social anxiety.

This case study centers on twenty-two-year-old undergraduate student Collette, who was diagnosed with social anxiety disorder two years ago. Collette’s social anxiety began after she moved to a new school after tenth grade. She began to experience low moods, apprehension about her health, and avoided activities with her friends such as soccer. When she started university, she began to feel paranoid, worried that people would think that she was strange or a loner. She stopped trying to make friends and stopped attending her classes for fear that she would say something stupid or embarrass herself. She also began to experience physiological symptoms – her face would flush, and she would sweat profusely. She was shaky and her chest felt tight. Eventually her anxiety became so impairing that she attempted suicide and ended up spending a week in the hospital. Following that week, she was invited to participate in a brief cognitive-behavioral group intervention study.

“On the first day, I met the group facilitators and the other participants. We filled out a number of questionnaires. Then we were introduced to the psychoeducation component of the program. We learned about the anxiety cycle and received a lot of useful information on how exposure to anxiety-related sensations can trigger negative cognitions about potentially hazardous outcomes.

On the second day, we learned how certain types of thinking errors, coupled with anxiety-related sensations, could increase our risk of having more intense anxiety and even panic attacks. The facilitators showed us how to identify these thinking errors or “dysfunctional thoughts.” We were instructed in ways to challenge these dysfunctional thoughts by examining the evidence (“what are the chances that the harmful consequences will occur”), de-catastrophizing (“what if this consequence did occur”), and substituting anxiety-provoking cognitions with more reasonable thoughts (“what is another way of looking at it”).

On the third day of the group, we were asked to meet the facilitators in one of the campus gyms. At the gym, we engaged in ten minutes of running, after which we were assessed for current physical sensations and our reactions to these sensations, such as feelings of breathlessness, suffocation, losing control, numbness, and so forth. The facilitators explained the rationale for doing the running as an “interoceptive” technique designed to expose us to sensations that resemble anxiety, sensations that can be frightening for highly sensitive people. At the end of the third session, we were given a homework assignment in which we were asked to complete ten minutes of running on at least ten additional occasions prior to coming back for a three-month follow-up session. After each running session, we were to complete the same assessment of physical sensations and our reactions to them. At first, I was quite bothered by the sensations, and on that first day in the gym, I even worried that others in the group would notice how breathless I was after exercise and think I was really strange because of how I gasped for breath. But eventually, with practice at running, this became the most enjoyable part of the program.

Over the past year, I’ve continued to struggle with anxiety but made significant progress. I still hear the little voice in the back of my head telling me that I’m being judged, that people think I’m socially awkward, or that people notice my nervousness, but I drown out that voice with positive self-talk. I find that it really helps me to reaffirm the irrationality of the initial negative thoughts. Now, when I enter a stressful or anxiety-provoking social situation, I ask myself: What’s the worst-case scenario? What are the odds that it’s likely to occur? And what if it did? So what? Would I never be able to get over it? Of course I would.”

CBT and Indigenous practice – O’SHEA ET AL.

Indigenous knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples has long included the health and wellbeing of individuals, as well as the wellbeing of cultural practices and community networks. This differs from the predominant Western mental health practices, which focus primarily on individuals. This lack of consideration for Indigenous knowledge leads to a gap in cultural competency and, subsequently, poorer access to mental health services for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples compared to non-Aboriginal Australians.

To aid with this, research has been done to explore the unique benefits of CBT as well as the tools and benefits of Wayapa Wuurrk, an Indigenous well-being practice that focuses on the wellbeing of the natural environment and kinship. This research took the form of workshops with both CBT and Wayapa practitioners. Participants took part in a social yarning session, which consisted of informal discussion to help build connection and trust between participants. Following this, participants took part in two workshops that described the practices of both CBT and Wayapa to build a shared understanding of each practice. The next day participants had the chance to discuss the unique traits of Wayapa and CBT, along with what both practices share with each other.

Results of this discussion produced a few key findings. One unique feature of Wayaba is that clients are not separate from the world around them. It is important for clients to use mindfulness and try to connect with wisdom and knowledge from the world around them and their ancestors. This connection to the Earth is a key feature of the practice, and advocating for environmental action and practicing physical movements that connect people to the Earth is so important. Unique to CBT were structured tools that could be used to really understand the connection between thoughts and behaviours, as well as the fact that there is so much scientific evidence that supports its effectiveness. Both practices share a common goal of wanting people to be well and encourage clients to explore themselves through their mind and their body. This study emphasizes the need for better cultural understanding in mental health practices and offers insight into ways mental health professionals can work towards bridging the gap.

Summary/Conclusion

CBT continues to be an effective route for the treatment of many psychological and physical disorders. By understanding the ways in which our behaviours and our cognitive processes are related, we are able to identify the maladaptive or harmful patterns and restructure our ways of thinking. Being the most widely researched form of psychotherapy, CBT’s strengths have been strongly empirically supported, making it a valuable approach for therapeutic practice. This wide body of research is helpful not only for recognizing these strengths, but also for recognizing the gaps in CBT and what kind of changes are needed to address them. As practice and research continues, CBT will continue to evolve and adapt so that its delivery can be expanded into more diverse formats and populations.

Test yourself!

Media Attributions

- Common Cognitive Distortions Aug23 © Pittard and Pössel (2020.) adapted by Yanna Kachafanas is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Example Thought record Aug23 © Yanna Kachafanas is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Perception Aug23 © Yanna Kachafanas is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Thought Aug23 © Yanna Kachafanas is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- roadmap adapted by Madison Conrad

- people © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- VR!

A therapy combining cognitive and behavioural techniques to change thoughts and behaviours.

A CBT approach that challenges irrational beliefs to reduce distress.

Unhelpful ways of interpreting experiences that maintain distress.

The therapist and client are working together to test and revise beliefs.

Teaching clients about mental health, conditions, and coping strategies.

Replacing distorted thoughts with more balanced, realistic ones.

Techniques to change behaviours, such as exposure or skills training.

Biased or inaccurate thinking patterns that fuel negative emotions.

Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic nations overrepresented in psychology research.