3 Clinical Assessment

Amara Kohlert and Dr. Laura Lambe

Psychological assessment

Let’s imagine you are a psychologist working in a school setting. You receive the following referral information for Amani:

Client: Amani, a 10-year-old child

Referral Reason: Amani was referred for a psychological assessment by her teacher due to concerns about her academic performance, particularly in reading and writing. Her parents also reported that she struggles with homework and often avoids reading tasks.

Developmental History:

- Amani was born full-term with no complications.

- She met all developmental milestones within the typical age range.

- There is no history of significant medical issues or neurological conditions.

Family Background:

- Amani lives with her parents and an older sister.

- Both parents are supportive and involved in her education.

- There is no family history of diagnosed learning disabilities, but her father reported having difficulties with reading during his school years.

- Amani’s family is of Arabic descent, and she speaks both Arabic and English at home.

- Amani and her family are permanent immigrants in Canada.

School Performance:

- Amani is in the 4th grade and attends a public school.

- Her teacher noted that Amani is attentive and well-behaved in class but struggles to keep up with reading assignments.

- Report cards show she is below grade level in reading and writing but shows average performance in math.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will have an understanding of what a psychological assessment would involve for Amani. In addition, you will be able to:

- Understand what is meant by clinical assessment.

- Understand why psychological assessments are conducted.

- Learn about the potential for errors in assessment.

- Look into various testing methods and key factors to consider when choosing the right tests.

- Understand the important role of ethics in psychological assessment.

- Recognize the impact of sociocultural factors on the assessment process and the value of feminist theories in psychological assessment.

History and Introduction

The practice of psychological assessment started in the 1890s with Lightner Witmer, who aimed to use psychological concepts to solve applied problems, like improving children’s school experiences by addressing issues such as children’s hyperactivity and behavioural problems (Vander Weg & Suls, 2014). A few years after, Sigmund Freud introduced psychoanalysis, which sought to explore and understand the inner world of the human psyche. This became the dominant theoretical orientation in clinical assessment during this time (Schwartz, 1999). As cultural emphasis on scientific theories grew, people became more interested in how biological and behavioural sciences were intertwined. This led to Freudian ideas being largely replaced by methods with stronger scientific support (Vander Weg & Suls, 2014). Gradually, new assessment methods like intelligence tests, projective tests, and behavioural tests were developed to meet the needs of the time (Abramowitz et al., 2023).

Today, clinical psychological assessment is often the first phase of communication that occurs between a psychologist and their client. Essentially, clinical assessment is the process of ‘getting to know’ someone, but in a more organized and comprehensive way than chatting over coffee. The goal of psychological assessment is to holistically understand the client’s life, thoughts, and behaviours, as well as any problems or concerns that led them to a clinical psychologist. In other words, the psychologist is usually tasked with answering a referral question in an assessment. Psychological assessment is a personally tailored process. This means that there is no one-size fits all approach to conducting assessment; rather, it is an interactive process between the client and psychologist. While there are general assessment guidelines psychologists tend to follow (discussed in The Steps of Clinical Assessment), the process will shift depending on the psychologist’s approach and the client’s needs.

The Types of Assessment

There are two main types of psychological assessment – stand-alone assessments and treatment-focused assessments – each with their own focus and goal.

Stand-Alone Assessments

Stand-alone assessments are conducted to answer specific questions or provide particular information. Stand-alone assessments may be conducted for several different purposes, including screening, diagnosis/case formulation, and prognosis/treatment. Among assessments conducted for each of these purposes, the psychologist’s role is primarily the assessor; the psychologist generally does not participate in any subsequent intervention or treatment that may be recommended (contrarily, see Treatment-Focused Assessment).

Screening assessments are used to help identify individuals who may have clinically significant problems or are at risk of developing such issues. Screening can be proactive by identifying individuals who may require psychological services but have not sought them out. This process often takes place before referrals or at first appointments. For instance, new patients at a health clinic might be asked to complete the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10). This helps clinicians determine the severity of substance use and whether further assessment or intervention is needed. Routine screening is sometimes conducted to detect early symptoms before they become severe. Screening interventions for early detection of mental health issues might occur at schools, workplaces, and primary care. Screening tools are designed to be highly sensitive, capturing all potential cases for further assessment. However, this means that some individuals flagged by the screening may not necessarily need psychological services for the specific issue being screened. In other words, they tend to prioritize sensitivity over specificity (sensitivity and specificity are discussed more in Theoretical Frameworks).

Other assessments are conducted primarily to answer a referral question and often involve the formulation of a case and the communication of a diagnosis. Diagnosis involves identifying and classifying a disorder, while case formulation goes beyond this and provides a comprehensive description of the patient, detailing their situation, current problems, and hypotheses linking psychosocial factors to their clinical conditions. Diagnoses and case formulations are often formed from multimethod data. This approach involves gathering information from interviews, psychological testing, informant reports, and other sources (e.g., school report cards, medical charts), and synthesizing this data to describe the presenting problem. Creating a case formulation can help the client to understand their situation, enhance communication about their strengths and difficulties, guide treatment planning, and provide clearer understanding of the etiology and prognosis.

Depending on the presenting concern, recommendations may include specific evidence-based psychological treatment, academic accommodations, referral to other healthcare practitioners (e.g., for medication), and self-help resources.

Treatment-Focused Assessments

Psychological assessment can also be conducted with a treatment-focused approach. In this case, the assessment is not a stand-alone service but is integrated as the initial part of an intervention and/or used throughout the intervention. This process builds upon the same steps as a stand-alone assessment, but importantly includes a greater focus on treatment planning, monitoring, and evaluation.

In some cases, assessment or case conceptualization might occur during the first session between a therapist and client. For example, the intake interview is usually conducted with the goal of gathering information on the presenting concern, identifying potential contributing factors to the issue, and developing a goal and a treatment plan for the sessions that follow. An intake interview is less formal than a stand-alone assessment, as there is no case report developed; rather, they serve as a primary step in developing trust and familiarization between client and therapist.

Diagnoses vs Case Formulation

Let’s review the difference between a diagnosis and a case formulation using a case example, Dakota. He is an Indigenous adult male, currently presenting for treatment for low mood.

Case Formulation:

Biological Factors

- Family History: There is a family history of depression, with Dakota’s mother having experienced similar symptoms.

- Sleep Disturbance: Difficulty sleeping contributes to fatigue and low energy levels.

Psychological Factors

- Cognitive Patterns: Dakota reports feelings of hopelessness and low self-esteem, which may be linked to negative thought patterns.

- Behavioural Changes: Withdrawal from activities and social interactions, leading to increased isolation and worsening mood.

Social Factors

- Cultural Identity: Dakota’s connection to their Indigenous community and cultural practices is significant. The loss of interest in cultural activities may impact their sense of identity and support.

- Work Stress: Decline in work performance and frequent sick days may contribute to feelings of inadequacy and stress.

- Community Support: The importance of community and cultural identity in Dakota’s life suggests that integrating community support and traditional practices could be beneficial.

DSM-5-TR Diagnosis: Major Depressive Disorder. Dakota meets 6 of 9 depressive symptoms outlined in the DSM-5-TR (5 required for a diagnosis, in addition to other duration and exclusionary criteria).

- Depressed Mood: Dakota reports feeling sad most of the time.

- Loss of Interest: They have lost interest in activities they previously enjoyed.

- Sleep Disturbance: Dakota has difficulty sleeping.

- Fatigue: They experience a lack of energy.

- Feelings of Hopelessness: Dakota reports feelings of hopelessness and low self-esteem.

- Impaired Functioning: Their work performance has declined, and they have been taking frequent sick days.

Case Formulation Summary: Dakota’s depression appears to be influenced by a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors. The family history of depression and sleep disturbances contribute to their symptoms. Psychologically, negative thought patterns and behavioural changes, such as withdrawal from activities, exacerbate their condition. Socially, the loss of interest in cultural practices and work-related stress further impact their mental health. A comprehensive treatment plan should address these factors, incorporating individual therapy, cultural integration, family and community involvement, and workplace support.

Once treatment has begun, the psychologist is also responsible for monitoring how the client responds to this treatment. The process of treatment monitoring involves collecting client data throughout an ongoing treatment process, assessing this data, and adapting treatment focuses as needed. In practice, this may involve asking clients to complete outcome measurements at regular intervals to provide the psychologist with information that will allow them to check the progress and change the treatment plan as needed. For example, if a client demonstrates that they are progressing well in response to treatment, a psychologist might consider shortening the treatment plan. Contrarily, if the client is not progressing as hoped, the psychologist might consider changing the plan or course of treatment. Take Dakota, our case example. Dakota is a 30-year-old Indigenous individual who has been referred to a clinical psychologist by their primary physician due to concerns about Dakota’s mood and behaviours. The clinical psychologist diagnosed Dakota with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Treatment monitoring in Dakota’s case might look like the psychologist asking them to rate their mood every session. If their mood is not improving across sessions, the psychologist can flag this as a problem and can readdress the treatment plan designed for Dakota’s MDD diagnosis. Other examples of treatment monitoring might include weight monitoring in the context of eating disorders, asking clients to rate how much their anxiety interfered with their work every week, or recording the number of days that someone attended their classes. Barkham et al. (2023) conducted a narrative review of routine treatment outcome monitoring in therapy and patient outcomes. Outcome monitoring was found to be a low-cost method to improve patient outcomes resulting in increased therapeutic success rates, and it was found to be especially important for shorter-term therapies. These findings highlight outcome monitoring as an important and accessible method that psychologists should be actively incorporating in their practices in order to improve their patient’s outcomes. Using outcome monitoring is an example of using evidence-based practices, since it combines past research and active practices.

Treatment evaluation in similar to treatment outcome monitoring, but it is done on a broader scale, and it is more specific to the treatment intervention itself than the client outcomes. Treatment evaluation is used to evaluate psychological services. For example, a psychologist might evaluate the client’s treatment outcome data relative to their baseline data. This allows researchers to determine how effective treatment methods are in achieving their goals (e.g., how effective a treatment designed to reduce depression severity is at actually reducing severity of depressive symptoms), to document the range of typical treatment outcomes, and to establish the necessary characteristics of successful treatment methods (e.g., desired length of time or number of sessions). Treatment evaluation is another great example of evidence-based practices, as its benefits in improving client outcomes has been scientifically validated.

Test yourself!

The Steps of Clinical Assessment

As mentioned, although the assessment process is largely personalized, there are general steps through which a clinical psychologist typically progresses.

Determine the Reason for Referral and Presenting Problem

In most cases, the first step in the clinical assessment process involves identifying why the client is engaging in these services, which is usually done through a clinical interview and by reviewing their referral information (e.g., documentation completed in advance, such as a background questionnaire or assessments by other healthcare providers). Of course, our lives and problems are multi-faceted and complex. The problem that the client presents will not necessarily be the direct issue that will be addressed. Presenting problems are often nuanced and more intricate than clients can recognize or articulate (Wright, 2020). For example, a client may identify their presenting problem as feeling overwhelmed by their responsibilities at home and work. Upon assessment, it may be identified that the client has a lack of interpersonal boundaries and difficulty saying no in relationships, which is affecting them in other areas of their life.

It may also be useful to consider the referral source. For example, referrals might come from the client (self-referral), their relative (e.g., a parent), their school, a physician, an employer, a lawyer, or be court-ordered. Information on who provided the referral can also help the clinical psychologist to identify the goals of the assessment. Imagine that a child is referred to a psychologist for behavioural issues. If the referral is coming from the child’s teacher, the goal might be to identify what learning accommodations will best support the student. If the referral is coming from a guardian, the goal might be to develop strategies to improve family dynamics.

Amani’s Case

Reason for Referral: Amani was referred for a psychological assessment by her teacher due to concerns about her academic performance, particularly in reading and writing. Her parents also reported that Amani struggles with homework and often avoids reading tasks.

Presenting Problems: Amani is performing below grade level in reading and writing, which has raised concerns among her teachers and parents. She appears anxious and frustrated when tasks involve reading or writing. Amani’s parents have noticed that she avoids reading tasks at home and struggles with homework. While attentive and well-behaved in class, Amani struggles to keep up with reading assignments.

Choose What to Assess

After identifying the presenting problem, the psychologist considers what additional information to gather. These decisions are guided by the client’s articulation of the presenting problem, other existing data sources (e.g., assessments by other healthcare professionals), and by the psychologist’s conceptual understanding of the problem. Providing evidence-based care in choosing what to assess involves active reference and incorporation of scientific theory. This can be seen in practice when psychologists refer to psychological theories of human behaviour and functioning to help them choose what to assess about their client. Consider a situation in which a client’s presenting problem is that they are having difficulty paying attention. A clinical psychologist should not only plan to assess for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but they should also be assessing for other possible reasons for attention problems, like learning difficulties, mood symptoms, anxiety, etc. Referring to published studies, a psychologist might also discover that sleep levels and other environmental factors, like socioeconomic status, are related to one’s ability to pay attention, which may lead them to also assess these factors as well (Tremolada et al., 2019). Psychologists should plan their assessments with a careful balance of measures that will provide data to “rule in” hypotheses and “rule out” competing hypotheses.

As such, there is a wide range of characteristics that a psychologist might choose to assess, including demographics, mental status, history of problem, social history and functioning, medical history, developmental history, family history, intellectual functioning, occupational functioning, hobbies and interests, and substance use. A holistic approach that involves assessing multiple characteristics is often best when conducting clinical assessment. However, this must be balanced with practical considerations. Time constraints and a client’s availability should be considered. Client’s may be travelling from far away, may be taking off time from their work and responsibilities, and/or may only be available for one session. Financial considerations might also play a role in assessment. Assessments often cost a lot of money, and clients are not always in a position to pay for multiple assessment sessions. There may also be limits to the amount of questions a patient is willing to answer before feeling overwhelmed or frustrated.

Amani’s Case

The psychologist chose to assess cognitive abilities, academic achievement, reading-specific skills, behavioural and emotional functioning, cultural and linguistic factors, and social and environmental factors. For Amani’s case, this might take almost 10 hours (!!!), including 1.5 hours for a clinical interview, 6 hours for cognitive testing, and 1 hour each for parents and teachers to complete questionnaires.

Select Method(s) of Assessment

Now that the psychologist has decided what to assess, they must determine how to assess it. This involves considering several factors, such as the client’s presenting problems, logistical concerns like the time required, and ethical considerations to ensure the methods are reliable and suitable for the client.

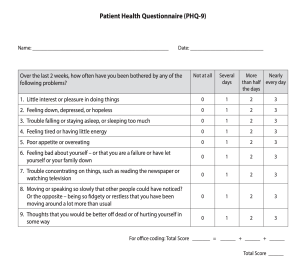

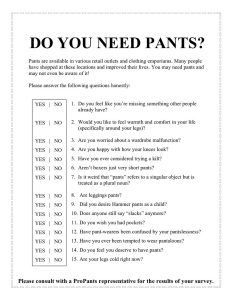

There are thousands of tools for gathering information, including clinical interviews, behavioural observations, questionnaires, projective tests, and standardized testing. Further, many variations of tests exist within each of these categories, and there may be many potential options for measuring the same variable. For example, there are over 20 different measures of depression (Breedvelt et al., 2020). The PHQ-9 scale and the Hamilton rating scale, for example, are both psychometrically valid rating scales used to assess depression. So, how might a psychologist pick which measure to use? They may consider an array of things, such as a client’s reading level, their time availability, and the cultural relevance of the scale. The method selected will also depend on the psychologist’s theoretical orientation. For example, behaviourists might prefer behavioural observations, while psychoanalysts might use projective tests more often. Different clients may respond better to different methods, highlighting the interactive nature of assessment.

Testing, in particular, involves the use of evaluative tools that yield scores on particular measures (more on this in later chapters!). Tests provide specific measurements and are often just one component of the broader assessment. Administering and scoring tests require specific training to ensure that proper standards are met. Formal tests, such as questionnaires or checklists, are often norm-referenced tests, meaning they have been standardized so that all test-takers are evaluated in a similar manner. Norm-referenced tests compare individuals’ scores to scores from a group of people who have already taken the test, called the standardization sample. For example, a person’s scores of the Beck Depression Inventory, a self-report questionnaire used to measure the severity of depression, would be compared to a normative sample to determine the individual’s level of depressive symptoms. Similarly, a norm-referenced test of a child’s reading abilities might rank the child’s performance compared to other children of the same age or grade level. There are certain principles that psychologists must follow when using psychological testing to ensure that all tests are administered and scored consistently, which is especially important for normative tests.

Gather the Data

With the major of decisions on what and how to assess made, and after obtaining informed consent, the psychologist can start collecting data. The goal of obtaining informed consent for assessment is to ensure that the potential client knows what to expect and is prepared to make an informed choice whether they wish to proceed. For example, with diagnostic assessments, patients should be made aware that they may or may not receive a diagnosis, and that their diagnosis may or may not be the one which was expected or hoped for.

Because of the complexity of the human experience, one method alone may not capture all the necessary information, so multi-method assessments, which is an approach that emphasizes the importance of obtaining information from various sources, in various settings, and form various methods, are often used. Using multiple methods of testing allows for psychologists to gather more solid data and have more confidence in their findings (Wright, 2020).

Self-report measures are commonly used among psychologists. Self-report tests allow individuals to provide insight into their own innermost thoughts, which can be very informative for a psychologist. However, these tests assume that people are accurate and honest in their self-assessments, which may not always be the case. Social desirability bias, the tendency for people to present themselves favorably, can affect accuracy of self-reports (Larson, 2018). For example, people tend to overrepresent their height and underrepresent their weight in self-report measures (Burke & Carman, 2017). Social desirability might also impact reporting on sensitive topics such as drug use and sexual behaviours (King, 2022; Kammigan et al., 2018). There are various factors that can influence this misreporting, including how the questions are administered and the participant’s desire to conform to social norms (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007)

For example, imagine a psychologist is assessing Dakota’s depression. The psychologist might (a) directly interview the client, (b) ask the client to complete a self-report questionnaire, and (c) interview the client’s close family members. Each method may provide the psychologist with a different subsection of the whole picture they wish to capture, increasing reliability and validity. In Dakota’s case, information was collected directly from Dakota and through talking with Dakota’s family. Dakota underreported their depressive symptoms during their interview, but their family members reported higher levels of depression than Dakota acknowledged. By combining these various sources of data, the psychologist gains a comprehensive understanding of Dakota’s depression, leading to a more accurate diagnosis and effective treatment plan.

Amani’s Case

The interviews reveal that Amani’s bilingual background and cultural identity play a significant role in her learning experience. While bilingualism can be an asset, it may also present challenges in a predominantly English-speaking academic environment. Cultural expectations and the importance of academic success within her family are also noted.

Consider Data and Draw Conclusions

After administering the tests, conducting interviews, and/or making observations, psychologists start to combine all of the collected data and draw conclusions. This data collection process will look different depending on the types of testing used. It may involve adding up scores or identifying common themes within interviews. The goal is to synthesize the collected data from all methods and merge them to create one cohesive story to answer the referral question.

It is important to recognize the ethical implications and responsibilities within this step. Conclusions drawn can be of great consequence for clients. A psychologist’s diagnostic decision might determine whether a client is able to access disability tax credits or school accommodations, if they are able to keep their driving license, or whether they can continue in their desired career path. In pursuing a career in policing with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, for example, applicants must undergo psychological testing, assessing factors in teamwork, emotional self-control, and decision-making under stress (RCMP, 2024). Making a diagnosis or not might also shift how a client sees themselves or how others see them (O’Connor et al., 2018). While every psychologist may draw their conclusions through a unique approach, providing evidence-based care involves ensuring that the conclusions drawn have a firm foundation in scientific, psychological theory and can be clearly justified.

Ethical Considerations

Consider the various consequences and ranging ethical weight that conclusions of an assessment might carry in the following situations:

- Custody dispute resolutions

- Competency to stand trial

- Testing accommodations for university exams

- Recommendations for inpatient or outpatient treatment

- Psychiatric diagnoses and labels

- Use of psychiatric medicines

Amani’s Case

Conclusions: Based on the comprehensive assessment data, the following conclusions may be drawn:

- Diagnosis: Amani meets the criteria for a Specific Learning Disorder with impairment in reading (dyslexia).

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Factors: Amani’s bilingual background and cultural identity are important considerations in her learning experience. While these factors do not cause the learning disability, they influence how Amani experiences and copes with her academic challenges.

- Emotional and Behavioural Impact: Amani’s academic struggles are contributing to elevated levels of anxiety and frustration, which in turn affect her overall well-being and academic performance.

- Need for Targeted Interventions: Amani would benefit from targeted reading interventions that focus on phonemic awareness, decoding skills, and reading fluency. Additionally, accommodations such as extra time on tests and the use of audiobooks can help mitigate the impact of her reading difficulties.

- Supportive Environment: Engaging Amani’s family and school in the intervention process is crucial. Providing culturally sensitive support and ensuring that interventions are tailored to Amani’s unique needs will enhance their effectiveness.

Disseminate the Findings

The purpose of all the previous steps come to fruition in the dissemination step. Psychologists will often compile all information gathered during the assessment to create a formal written report to communicate their findings. The assessment report tells the story of the clinical assessment, detailing information from each step of the process, usually starting with the presenting problem and ending with explanations of how conclusions were drawn. The format of this report can vary between psychologists and depending on intended audience, but they typically include background information, test results, interpretations, and appropriate recommendations. If appropriate (and if the client provides consent), a copy of the confidential report may be shared with the client, a parent, the courts, or school personnel, so that actions following the recommendations can be made. If the purpose of the assessment is simply to inform treatment (e.g., an intake interview), the psychologist may simply communicate their conclusions and recommendations orally with the client, as well as document this process in their health record. For example, a psychologist may summarize a client’s intake interview by saying they are currently experiencing symptoms of depression and develop a plan to have the client come back for weekly therapy.

Assessment as a Fallible Process:

Theoretical Frameworks

Clinical assessment, while scientifically based, is inherently imperfect due to its human element, which introduces the potential for errors. Clinical psychologists cannot achieve 100% accuracy in their assessments and judgements.

As described above, psychologists may use various tools (e.g., a self-report scale, structured clinical interview, etc.) to inform their assessments and diagnostic decision-making. While tools do not “diagnose” – this is a clinician’s job – the information provided by each tool must be carefully considered in terms of its sensitivity and specificity:

- Sensitivity refers to the ability for a tool or measurement to identify true positives. In other words, it refers to a tools ability to truly detect a signal if it exists (i.e., its ability to detect people with a condition). A tool with high sensitivity is less likely to overlook individuals who genuinely need intervention or treatment.

- Specificity, conversely, refers to the ability for a tool or measurement to identity true negatives (i.e., its ability to detect people without a condition). High specificity ensures that people without the disorder are not mistakenly diagnosed, which is crucial for avoiding unnecessary and inappropriate treatment.

Sensitivity and specificity may also be influenced by human factors. As we know, clinical psychologists are situated beings who exist within their contexts, each with their own previous experiences and judgements. For instance, a clinical psychologist who has an initial hunch that their client has ADHD might overlook data that suggests otherwise. This confirmation bias might cause a clinical psychologist to prioritize specificity (the ADHD diagnosis) over sensitivity (the true condition). In another case, a psychologist’s judgment might be influenced by an availability heuristic. They may have recently read a book about the prevalence of anxiety and may therefore be more incline to diagnose their client with an anxiety disorder. Other factors, such as overconfidence in own judgement, fatigue, and stress levels may affect this sensitivity and specificity balance.

![Drmfreeman, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons A 2x2 contingency table showing test accuracy metrics. The rows represent test results (Positive, Negative), and the columns represent actual condition status (Yes, No). The table includes: True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), False Negative (FN), and True Negative (TN). It also displays formulas for Positive Predictive Value [TP/(TP+FP)], Negative Predictive Value [TN/(FN+TN)], Sensitivity [TP/(TP+FN)], and Specificity [TN/(FP+TN)].](https://pressbooks.atlanticoer-relatlantique.ca/app/uploads/sites/944/2025/05/Contingency_table_of_test_accuracy_metrics-300x277.png)

These examples work to remind us that clinical psychologists are not blank slates; their decisions are shaped by their experiences, and as such, there is a potential for error in clinical assessment. Clinical psychologists should be informed about the potential for error when selecting their methodologies to achieve an appropriate balance of sensitivity and specificity. This balance should align with their professional and ethical standards.

Clinical Judgement vs Actuarial Prediction

Given the potential for human error and the (potentially) high consequences of misdiagnoses, you may be wondering if humans are really cut out for this job! The use of computers (think statistical models and algorithms) has also been explored as an avenue for clinical decision-making. This is known as actuarial prediction. In clinical psychology, clinical judgement and actuarial prediction represent two contrasting approaches to making predictions about a client’s future behaviour, treatment outcomes, or diagnosis.

Clinical judgement involves drawing conclusions or making decisions based on expert knowledge, personal experience, clinical intuition, and other subjective insights from the clinician. The theory supporting clinical judgement suggests that the expertise, knowledge, and skills that a psychologist has accumulated through experience can provide more accurate conclusions about individual cases than those derived solely from a statistical or research-based criteria. In this view, it is the very fact that clinical psychologists are not blank slates, and rather that they are situated individuals, which is argued to make their clinical judgement sharper. However, clinical predictions are also more prone to biases, with many diagnoses having relatively low inter-rater reliability between practitioners (Rettew et al., 2009).

In contrast, actuarial prediction relies on statistically determined probabilities to make judgements and decisions (e.g., the likelihood of an individual responding to a particular treatment, reoffending after release from prison, developing a psychiatric disorder, or committing suicide) (Abramowitz et al., 2023). This approach is more objective than a clinical judgement approach as it removes the human factor by making decisions based solely on data from research findings. Research largely demonstrates that actuarial prediction is more accurate than clinical judgement (Ægisdóttir et al., 2006). Actuarial prediction consistently reaches the same conclusion when given the same information, whereas even experienced psychologists may struggle to synthesize all relevant data and can be susceptible to cognitive biases and other influencing factors.

This is not to say that actuarial prediction should always be the answer. Actuarial methods may be limited in situations that require personalized or context-sensitive insights, making a human perspective essential. For example, within the criminal justice system, there is debate concerning these two methods of decision. Actuarial prediction is used to make decisions about child maltreatment, juvenile delinquency, recidivism, violence prediction, sentencing, parole, and probation (Schwalbe, 2008; Smee & Bowers, 2008; Barabas et al., 2018). While actuarial prediction is understood to offer neutral, bias-free decisions, there are concerns about the underlying statistical techniques of actuarial prediction reproducing cycles of discrimination. Actuarial prediction methods are largely based on regression models which have been mainly derived from research of white men’s likelihood of committing criminal behaviour. Critics argue that actuarial methods overlook the underlying social, economic, and psychological drivers of crime, and this continues to perpetuate existing discriminatory cycles within the justice system. They advocate for a shift towards a methodology that combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches (Barabas et al., 2018). This example works to highlight the danger in viewing clinical judgement and actuarial assessment as mutually exclusive methods . There is ongoing debate within clinical psychology about the optimal balance between clinical judgment and actuarial tools, with many advocating for an integrative approach that combines the strengths of both.

Ethical Considerations

With the growing use of artificial intelligence, what ethical considerations might come into play when thinking about standardizing clinical assessment processes with actuarial prediction?

The Testing Process

Assessment as a fallible process

Returning to a question we asked in Choose What to Assess: with so many testing options, how do psychologists choose the appropriate methods? In addition to considering all elements covered in The Steps of Clinical Assessment, like the client’s presenting problem, potential root causes, logistics, and cultural relevancy (discussed more in Cultural and Feminist Considerations), the clinical utility of a testing measure is crucial for psychologists to consider. Clinical utility refers to scientifically proven components of a test that tell us about the test’s adequacy, relevance, and usefulness.

Reliability and Validity

| Reliability | |

| Test-retest reliability | The consistency of test scores across time |

| Inter-rater reliability | The degree of agreement between two or more raters |

| Internal consistency | The degree to which the items in a test all measure the same characteristic |

| Validity | |

| Construct validity | Made up by convergent and discriminant validities |

| Convergent validity | The extent to which a test of one construct correlated with other tests measuring the same construct |

| Discriminant validity | The extent to which a test of one construct is not correlated with tests of unrelated constructs |

| Predictive validity | The degree to which test scores can predict future outcomes |

| Incremental validity | The extent to which a test provides information not otherwise available |

In addition to clinician factors, the source of information (often the client) can also be fallible. Sometimes tests or psychologists will make a point to include effort testing in their assessments to help determine the validity of a client’s answers (i.e., their effort and truthfulness) and to detect malingering. This is an important step in determining whether the information gathered in an assessment is likely to be representative and a valid picture of the client’s current functioning, which the psychologist will need to make a statement on in their final report. Consider: the results of your client’s assessment may allow them to avoid military duty, or leave a correctional facility, or evade criminal prosecution. Why might effort testing be especially important in these examples?

In summary, while no test measure is perfect, the goal of using an evidence-based approach is to consider all options, understand a test’s strengths and weaknesses, and choose the most appropriate method available.

Cultural and Feminist Considerations

The Importance of Cultural Consideration

Culture influences the client-therapist relationship, treatment selection, and therapy outcomes (Soto et al., 2018). Client problems cannot be assessed and understood through sole exploration of client cognition, affect, and behaviour, but must be paired with an understanding of people’s lived experiences within the larger cultural and social context (Ratts & Pederson, 2014). Culture should always be considered in the assessment process, which is true regardless of whether culture has been extensively thought about or rarely contemplated by the client. A client’s psychological development, conceptualization of self, and worldview have all been forged within a cultural context. This is an especially important point to emphasize for psychologists who are members of the dominant culture, and who may not be as aware of or readily presented with the ways in which their practices and worldviews have been shaped by their culture. These points are also especially important to consider when working with culturally diverse clients.

The need for cultural humility in clinical psychology is becoming increasingly important considering the diversity in Canadian communities, requiring that psychologists adopt a multicultural approach to provide effective services. Practicing appropriate and culturally aware clinical assessment involves more than an awareness of human differences; it requires active efforts to learn about different cultures and to recognize the consequences of failing to do so. Using culturally inappropriate assessment practices may decrease the reliability or validity of an assessment and may have discriminatory and harmful consequences.

Ethical and Social Justice Considerations

Consider how a psychologist using an assessment that is not culturally appropriate might decrease the validity of the assessment. As in the example of Amani’s reading assessment, assessment results may be inaccurately inflated. What consequences might this have? Very obviously, there may be negative consequences of an inaccurate assessment for the client. More broadly, using culturally inappropriate assessment methods may work to contribute to ongoing social inequities and forced marginalization of communities.

A psychologist’s ability to acknowledge the role of culture in a client’s complex identity enables them to select culturally appropriate tests. Considering client culture goes beyond geographical, racial, and ethnic considerations to also include constructs like language proficiency, age of migration, generational status, length of residence, ethnic identity, and acculturation (Padilla & Borsato, 2008). For example, a more acculturated individual is to their host society, the more applicable standardized norms may be.

Psychologists should also consider how culture and society have shaped testing methods. Further, psychologists should be aware of how their own ethnic and cultural experiences and position in society influence their selection of tests. Appropriate cultural adaptations should span throughout the entire assessment process, including what instruments are used as well as how they are administered, scored, and interpreted (Padilla & Borsato, 2008). This adaptation process includes, but goes beyond, translation of assessment tools (Borsa et al., 2012). Assessment areas amenable to cultural adaptation include concepts, goals, and methods of the assessment (Soto et al., 2018). For example, cultural adaptations might also include holistic or spiritual conceptualization of wellness and engagement in cultural rituals for Indigenous peoples.

Consider the Historical Context

The development of assessment and clinical psychology services was not immune to the overt racism and systematic inequities within North American societies. An early theory in clinical assessment posited that focusing on similarities across racial groups, rather than acknowledging differences, would enable cultural coexistence. Unfortunately, this approach often came at the expense of minority individuals who have been forced to sacrifice their cultural identities. Consequently, clinical practices were designed to assimilate culturally diverse clients into White culture (Ratts & Pederson, 2014).

When cultural influences cannot be eliminated from tests, consideration of specific cultural variables should be incorporated to the assessment process. Psychologists should consider the content being assessed and whether it is applicable across groups. For example, ‘smack’ in England is used to refer to the Canadian concept of ‘spanking’. Psychologists must also consider how culture has influenced understandings of relations between constructs being assessed. Authoritarian parenting, for example, is associated with poorer childhood outcomes in Western contexts but not in Chinese cultures. When scoring, psychologists should also consider how culture and normative samples have influenced cut-off scores. Women, for instance, tend to score higher on some measures than men, necessitating different cut-off scores to avoid false positives.

Underrepresentation of Transgender and Nonbianary People

There is a significant underrepresentation of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-diverse people within psychological research (Norton et al., 2024). After discussing the importance of considering the normative sample in clinical assessments, what might some potential consequences of this lack of representation be for transgender, non-binary, and gender-diverse individuals? Researchers are increasingly recognizing the need to fill this gap in our research. Currently, assessment tests for disordered eating behaviours are being developed specifically for transgender, nonbinary, and gender-diverse individuals (Pham et al., 2024).

Multicultural assessment is a field of research which focuses on studying the extent to which psychological tests are valid for different populations. Many psychological tests are norm-referenced tests (more on this in Chapter 5!), meaning that a client’s scores are compared to the scores of a normative sample. It is important to critically evaluate the “normative sample” that was used to create testing norms. Norm-referenced tests derived from majority populations may have poor validity for individuals whose cultural identities differ from the normative sample. Such considerations are especially important when results will be used to inform treatments or academic accommodations, as discussed below.

Consider the Stakes

In low-stakes testing, there are typically no consequences associated with performance. For example, think about a weekly quiz that is used to provide a teacher with insight into what their teaching plan should cover in the following week. The consequences of failure to consider culture in high-stakes testing may be more severe. Consider standardized testing used to determine which students will be paced in a special education program. Research has revealed that there is an overrepresentation of minority students in special education programs (Morgan, 2020), which is troubling especially considering students in special education are more likely to experience higher teacher attrition and higher dropout rates (Billingsley & Bettini, 2019).

Creating culturally appropriate tests involves becoming knowledgeable and comfortable with traditional customs and communicative styles across cultures. Beyond training psychologists in multicultural awareness, minority community members should be involved in instrument selection and decision making when possible, and efforts should be made to increase the number of qualified non-white psychologists trained in psychometrics (Padilla & Borsato, 2008).

Feminist Thinking in Clinical Assessment

Cultural humility goes hand-in-hand with social justice work and feminist thinking. As psychologists gain multicultural competence, client problems can be seen more contextually, allowing gained insight into how oppression affects people’s lives and the ways in which systemic inequities lead to internalized oppression. Feminist thinking involves recognizing and working to alter existing power dynamics. It is based on social theories and political activism, working to combine both theory and practice (Ferguson, 2017). Gaining a cultural awareness, allowing for the recognition of client problems in context of inequity, is both an educational endeavor and a social justice endeavor (Ratts & Pedersen, 2014).

Intersectionality is another tool of feminist thinking that can be helpful when considering the value of multicultural assessment. Intersectionality is the theoretical framework that experiences of privilege and oppression vary due to the intersection of many social identities (i.e., race, class, gender, sexuality, religion, language, disability, age, etc.). Feminist work also relies on the tool of reflexivity, allowing thinkers to reflect on how ‘what they already know’ works to shape their subsequent understandings of the world.

Consider This

Historically, if an assessment theory was deemed to be academically ‘sound’ and was supported by ‘research,’ it was considered appropriate to use with any client. Consequently, clinical practices were designed to assimilate culturally diverse clients into White culture. These practices, despite falling in line with evidence-based theories, have worked to perpetuate harmful cycles of inequity (Ratts & Pederson, 2014).

Throughout this chapter, the importance of using evidence-based practices as a clinical psychologist has been continuously emphasized. Evidence-based practices, in line with the positivist method, relies on an idea that these practices are based in evidence, which is thought to enable unbiased thinking. Feminist theories of knowledge have argued against the idea of completely objective knowledge. Instead, feminist thinking recognizes knowledge as inevitably attached to and influenced by the social and physical situatedness of its knower (Wigginton & LaFrance, 2019). Just as no clinical testing method is acultural, no knowledge is completely objective. How, then, do evidence-based practices fit into these ideas? How can clinical psychologists aim to combine feminist thinking by using tools of intersectionality and reflexivity, recognizing existing power dynamics and their influences on our assessment methods, while prioritizing the importance of evidence-based practices? This issue has been referred to as ‘the gap problem’ (Intemann, 2005). Feminist scholars recognize the high importance in evidence-based practices but suggest also acknowledging the role of value-laden science, where evidence guides practice and decisions are made with justification (Goldenberg, 2015).

Test yourself!

Media Attributions

- screening

- Doctor greating patient © Vic is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- PHQ-9 © Robert L. Spitzer, Janet B.W Williams, Kurt Kroenke is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Do You Need Pants? questionnaire © Jason Eppink is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- RCMP officer on horse © Robert Thivierge is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Contingency_table_of_test_accuracy_metrics © Drmfreeman is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Screening is used to help identify individuals who may have clinically significant problems or are at risk of developing such issues.

Identifying and a mental health disorder based on symptoms, such as those outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR).

The study of the causes and contributing factors that lead to the development of a mental disorder.

A clinician’s informed prediction about the likely course, outcome, and recovery prospects of a mental disorder.

Ongoing measurement of client symptoms or functioning to track response to treatment.

The process of determining the effectiveness of a specific psychological intervention.

The main concerns or symptoms that lead a client to seek psychological help.

The person, agency, or organization that directs a client to a mental health professional for assessment or treatment.

Tests that compare an individual's performance to a standardized group.

The process of sharing information with patients that is essential to their ability to make rational choices among multiple options (Beahrs & Gutheil, 2001)

Using various tools and techniques to gather comprehensive information about a client.

The tendency for people to present themselves in a favorable light during assessments.

The ability of a test to correctly identify those with a condition (true positives).

The ability of a test to correctly identify those without a condition (true negatives).

The tendency to focus on information that supports one's initial beliefs and ignore contradictory evidence.

Judging the likelihood of events based on how easily examples come to mind.

The use of experience and expertise to make decisions in clinical settings.

Using statistical formulas to predict outcomes rather than relying on clinician intuition.

The usefulness of a test or procedure in helping clinicians make decisions or plan treatment.

Assessments designed to determine whether a person is putting forth adequate effort.

Deliberate faking or exaggeration of symptoms for external gain.

An ongoing process of self-reflection and learning in which individuals recognize and address their own cultural biases, remain open to others’ cultural identities and experiences, and approach each interaction with respect, curiosity, and a willingness to learn.