8 Intervention: Behavioural Approaches

Hannah Smith and Madison Walker

Now that you’ve finished an overview of clinical interventions, it’s time to expand your knowledge of behavioural approaches to intervention. Behavioural approaches are effective for learning or improving skills, increasing the frequency of positive/desired behaviours, as well as decreasing the frequency, duration, or intensity of undesired behaviours. From supporting individuals in achieving sobriety, building language skills, and helping people face phobias, behavioural interventions can have profoundly meaningful impacts on an individual’s well-being.

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Understand the history of behavioural techniques, including controversial uses.

- Apply learning theory to behavioural interventions.

- Identify the steps of behavioural treatment including defining and assessing behaviours.

- Describe types of behavioural interventions and the disorders for which they are evidenced-supported.

- Be able to critically evaluate the strengths and criticisms of behavioural techniques.

Introduction to Behavioural Interventions

What are Behavioural Interventions?

Behavioural interventions encompass a wide range of evidence-based techniques derived from the science of learning theory (See section 2). By leveraging principles of learning theory, behavioural interventions aim to reduce the frequency of challenging behaviours or negative emotions associated with those behaviours and promote positive behaviours. These approaches are utilized by practitioners such as clinical psychologists and behaviour interventionists to support individuals and their families. Behavioural interventions have very strong empirical support in the treatment of a variety of psychological disorders, and form a core component of first-line treatments for anxiety, depression, and OCD. Furthermore, behavioural techniques are often combined with cognitive strategies, forming the basis of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which will be explored further in Chapter 9.

A Review of Learning Theory

Learning theories form the basis of many of the behavioural approaches that will be discussed in this chapter. A strong understanding of learning theory will help you understand why different behavioural approaches are effective and how/why they were designed the way they were. As you read this chapter, consider how the principles of operant and classical conditioning apply to the various behavioural approaches.

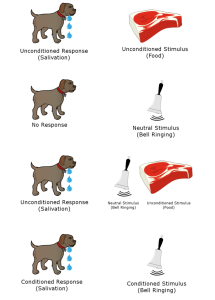

Review of Classical Conditioning

You probably remember learning about Ivan Pavlov’s experiments which demonstrated the ability of dogs to learn to associate a bell with food, and in turn, salivate when they heard a bell. This phenomenon, known as classical conditioning, is the process by which individuals come to associate a known stimulus with a previously neutral stimulus, causing the neutral stimulus to now elicit a response (Akpan, 2020; Pavlov, 1927). Let’s break this down a bit! The components of classical conditioning are:

Unconditioned Stimulus (US): The stimulus that elicits a response prior to any conditioning. In the case of Pavlov’s dogs, the unconditioned stimulus was the food presented to the dogs.

Unconditioned Response (UR): The behavioural response to the unconditioned stimulus. In the case of Pavlov’s dogs, the unconditioned response was the dogs’ salivation when they were presented with food.

Conditioned Stimulus (CS): The stimulus that comes to elicit a response after being paired with the unconditioned stimulus. In the case of Pavlov’s dogs, the conditioned stimulus was the bell.

Conditioned Response (CR): The behavioural response that develops in response to the conditioned stimulus over time (as it is paired with the unconditioned stimulus). In the case of Pavlov’s dogs, the conditioned response was the dogs’ salivation when they heard the bell.

Classical conditioning is involved in the development of phobias by associating a neutral stimulus with a fear response. For example, imagine a child developing a fear of dogs after being bitten. The bite (US) naturally triggers fear or panic (UR), but after this experience, the dog itself (CS) becomes enough to trigger that same fear or panic (CR), even without another bite (Akpan , 2020; Pavlov; 1927).

Review of Operant Conditioning

Like classical conditioning, you probably also remember learning about operant conditioning in previous psychology classes. Remember B.F Skinner’s Skinner box experiment using rats? In his experiment, rats learned to press a lever to earn a food reward; a perfect example of operant conditioning at work (Skinner, 1938; Skinner, 1963).

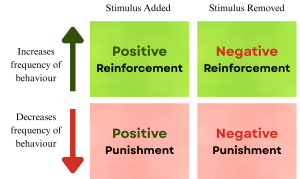

Operant conditioning explains how behaviours are shaped and maintained by their consequences. It refers to learning that occurs when a particular behaviour is followed by a desired outcome (reinforcement) or an undesired outcome (punishment). By manipulating these outcomes, the frequency of a behaviour can be increased or decreased over time (Akpan, 2020; Skinner, 1938; Skinner, 1963). The main outcomes in operant conditioning are:

Positive Reinforcement: Adding a stimulus to increase the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future. For example, imagine a child is working quietly on homework when a parent rewards the child with a small cookie. In the case, the cookie (added stimulus), increases the likelihood that the child will work quietly (the behaviour) in the future.

Negative Reinforcement: Removing a stimulus to increase the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future. For example, imagine a child is working quietly on homework when a parent rewards the child by removing one of the sheets of homework. In this case, removing a sheet of homework (removed stimulus), increases the likelihood that the child will work quietly (the behaviour) in the future.

Positive Punishment: Adding a stimulus to decrease the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future. For example, imagine a child is seated to work on homework but is not working and being very loud, so a parent punishes the child by adding a sheet of homework. In this case, adding homework (added stimulus), decreases the likelihood of the child being loud/inattentive (the behaviour) in the future.

Negative Punishment: Removing a stimulus to decrease the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future. For example, imagine a child is seated to work on homework but is not working and being very loud, so a parent punishes the child by removing the cookie sitting beside them. In this case, taking the cookie (removed stimulus), decreases the likelihood of the child being loud/inattentive (the behaviour) in the future.

Negative reinforcement is a powerful mechanism that maintains maladaptive behaviours across various forms of psychopathology. For instance, avoidance behaviours might reduce anxiety and bring relief, therefore reinforcing and increasing avoidance in the future. Further examples are checking behaviours, purging after a binge, and substance use (McCarthy et al., 2010).

Test yourself!

History of Behavioural Techniques

Behaviour therapy emerged between the 1950s and 1970s as an evidence-based approach for treating psychological disorders by applying learning theory to modify observable behaviour (Rachman, 2015). Key figures in its development included Hans Eysenck, who criticized the effectiveness of traditional psychotherapy and advocated for behaviour therapy, and Joseph Wolpe, who developed systematic desensitization to treat anxiety disorders (see section 5.4) (Rachman, 2015). Behavioural techniques have since been widely used to help individuals reduce challenging or harmful behaviour and learn new skills. For example, behavioural techniques have often been used to reduce or replace self-injurious behaviour in individuals with intellectual disabilities or autism (Matson & LoVullo 2008). As well, such techniques have been instrumental in improving skills related to language, personal care, and social interaction (Palmen & Lang, 2012).

Looking back: The use of punishment

Despite the benefits of behavioural techniques, the use of punishment within these approaches has faced significant criticism. One key criticism is that aversive procedures are coercive and might lead to ethical concerns regarding the rights of individuals, particularly when it involves vulnerable populations. An additional criticism is that punishment focuses on teaching an individual only what not to do, and does not teach desired alternative behaviours. As a result, individuals are more likely to revert back to undesired behaviours once the punishment is removed. Punishment has also been criticized for contributing to increased anxiety and stress in individuals, as well as lasting physical and psychological harm. While punishment was frequently used historically, current approaches aim to avoid the use of punishment wherever possible (Behaviour Analyst Certification Board, 2020; Harris & Ersner-Hershfield, 1978; Pokorski & Barton, 2021).

Behavioural Techniques in Conversion Therapy

One historical use of behavioural approaches that is now considered harmful is behaviour modification in 2SLGBTQIA+ conversion therapy. Previous research has documented the practice of subjecting 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals to nausea-inducing drugs and electric shock to the hands and genitals. These punishments would be delivered while the subjects viewed same-sex pornography in an attempt to reduce their arousal to the imagery (Haldeman, 2002). Other behavioural techniques designed to reduce same-sex sexual behaviour include the use of classical conditioning by superimposing mixed-sex pornographic images over same-sex pornographic images (Morris et al., 2021). Of course, today the ineffectiveness and harms caused by conversion therapy techniques are much more widely recognized.

Developments of Ethical Guidelines Related to Behavioural Techniques

One way to mitigate the potential for harms caused by the use of punishment and behavioural modification approaches is the development of ethical guidelines to prevent the harmful use of behavioural techniques and promote affirming, evidence-based treatments. To this end, there is a defined ethics code for behaviour analysts (BACB, 2020). This ethics code is comprehensive and includes many guidelines that extend beyond the scope of this textbook chapter, however, some specific guidelines relevant to the topics we have discussed include:

Minimizing Risk of Behaviour-Change Interventions: Avoiding restrictive treatments or punishment unless absolutely necessary (i.e., the target behaviour has not responded to any less restrictive treatments and may cause more long-term harm than the proposed intervention) (BACB, 2020).

Responsibility to Clients: Supporting the rights and autonomy of clients and engaging in a way that is in their best interest (BACB, 2020).

Applied Behaviour Analysis

What is Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA)?

ABA is a type of behaviour therapy practice that is based on the principles of operant conditioning and behaviourism. ABA focuses on behaviour change by reducing challenging or unwanted behaviours and by increasing positive behaviours or teaching new skills. While ABA has traditionally been associated with Autism, ABA can be a helpful approach for a range of individuals including those with Autism, intellectual disabilities, ADHD, Dementia, and anyone with behavioural concerns (Golshekoh & Pasha, 2017; Noguchi et al., 2013). ABA seeks to be evidence-based and provide meaningful change for individuals and their families (Baer et al., 1968).

ABA can include a range of assessment and intervention practices. This chapter will discuss interventions that fall under the umbrella of ABA practices such as the Functional Behaviour Assessment process (see section 4.2), Contingency Management (see section 5.1), and Social Skills Training (see section 5.3). These are just some of the types of behavioural approaches associated with ABA.

It is important to note that ABA has faced criticism, particularly when it has been used to modify individuals’ behaviour to make them act in a way that is more normative. Ethical ABA should seek to support the well-being of the individual, prioritize their goals, and celebrate unique personalities in a way that is neurodiverse-affirming (Contreras et al., 2021).

Process of Behaviour Treatment

Target Definition and Baseline Assessment

The process of behavioural treatment begins with defining the target behaviour, which is an observable behaviour identified as the focus of intervention. Practitioners will define the target behaviour using operational definitions.

An operational definition of behaviour describes the behaviour in a way that is observable and measurable. When writing an operational definition, practitioners typically avoid including assumptions about why a behaviour is occurring or what the individual is thinking or feeling (Hurwitz & Minshawi, 2012 ).

For example, a psychologist might operationally define biting as: Individual opens their jaw and makes contact between their teeth and another person’s skin.

While an example of a definition that is not operational would be: Individual intentionally opens their jaw, and makes contact between their teeth and another person’s skin in an attempt to hurt the other person and/or make them cry.

Once the target behaviour is clearly defined, practitioners will measure the frequency, intensity, and duration of the target behaviour. They might ask questions to the client like, “How often is this behaviour happening? How long does it occur for? What is the intensity with which it is occurring?” (Hurwitz & Minshawi, 2012). These measurements are used to form a baseline of the behaviour, ensuring that progress can be monitored throughout treatment. Subsequent measures can then be compared to this baseline to assess any changes resulting from treatment, or if it is necessary to adjust the plan.

Functional Behaviour Assessment

The next step in the process of behaviour treatment is functional behaviour assessment (FBA). FBA is used to determine the function of a particular behaviour, or the reason why an individual is engaging in a particular behaviour. Knowing why an individual is engaging in a challenging behaviour can help professionals understand how to help that person reduce the frequency of that behaviour (Alter et al., 2008).

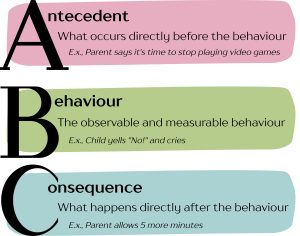

Another component of the functional behaviour assessment process is determining what happens directly before a behaviour (this is called an antecedent) and what happens directly after a behaviour (this is called a consequence). As we will learn, knowing about these events are often critical to determining the function of behaviour. Professionals often refer to this concept as the ABC’s of behaviour (Samudre et al., 2021):

A (Antecedent): What occurs directly before the behaviour

B (Behaviour): The observable and measurable action taken by the individual

C (Consequence): What happens directly after the behaviour

Setting Events: Events that make it more likely that a behaviour that will occur. For example, getting a bad night’s sleep or missing a dose of medication might make an individual more likely to engage in challenging behaviour (Kennedy & Itkonen, 1993; Wahler & Fox, 1981).

Callout

Functions of behaviour are complex, and often individuals engage in behaviour for more than one reason. Regardless, there are four main categories that professionals sometimes use to classify these functions (Hanley et al., 2003). They can be remembered using the acronym SEAT:

- Sensory: Feeling some sort of desired sensory input.

- Escape: Avoiding an item, activity, sensation, person, etc.

- Attention: Receiving attention (whether positive or negative) from another person.

- Tangible: Gaining access to a desired item or activity.

Test yourself!

To determine which of these functions might be contributing to a behaviour, a practitioner will conduct a functional behaviour assessment (FBA) (Alter et al., 2008). An FBA may include the following steps:

- Indirect Observation/Functional assessment interview

- Direct observation (Collection of ABC Data)

- Functional Analysis (Sometimes optional)

Indirect Observation/Functional Assessment Interview:

This first part of the process involves getting a good sense of the behaviour, what it looks like, when it happens, and what events happen before and after. Often, a practitioner will conduct interviews with the individual, their family, and sometimes the people around them in their lives, depending on the situation (Fee et al., 2016; Kern et al., 1994). For example, If a child is engaging in challenging behaviour at home and school, the practitioner might interview the child’s caregiver(s) and teacher.

Throughout the interview process, the goal is often to begin to determine any setting events, antecedents, or consequences, and use this information to form a preliminary hypothesis about the function of the behaviour (Fee et al., 2016; Kern et al., 1994).

Callout

Direct Observation:

While a Functional Assessment Interview may provide the practitioner with some preliminary evidence to form a hypothesis about the function of behaviour, the next step of the FBA process is to directly observe the behaviour and record what happens. This process is also sometimes known as ABC data collection (Samudre et al., 2021).

ABC data collection can be completed by a practitioner or by another person close to the individual. Typically, a chart is used with columns labelled setting events (optional), antecedent, behaviour, and consequence. The person collecting data will watch for the behaviour, and when it occurs will take notes of what happened directly before, during, and after a behaviour. Sometimes this data collection will also include a section for setting events where the person can record any earlier events that may have potentially contributed to the behaviour occurring. In ABC data collection each line of data denotes a new instance of the behaviour occurring (Samudre et al., 2021). Table 1 illustrates what an ABC data chart might look like.

| Date/Time | Setting Event | Antecedent | Behaviour | Consequence | Notes (function?) |

| Tuesday

1:03pm |

Morning routine disrupted: Missed the bus | Classmate touched toy that E.K was playing with | E.K spits on classmate | Classmate exclaimed “ewww”, Teacher asked E.K to return to their desk | |

| Tuesday

1:21pm |

Morning routine disrupted: Missed the bus | Teacher presented E.K with math worksheet | E.K spits on teacher | Teacher removes math sheet from E.K desk and demanded E.K visit office |

Through analyzing the data presented in an ABC data sheet, a behavioural interventionist or clinical psychologist may be able to form a hypothesis about the function of behaviour. If the function of behaviour is still not clear, a functional analysis may be recommended (Lerman & Iwata, 1993).

Functional Analysis

A functional analysis is an optional step of an FBA that must be completed by a trained professional. Registered clinical psychologists and Board Certified Behaviour Analysts are some of the only people who have the training to conduct a functional analysis. Typically, functional analyses are completed in complex cases when the function of a behaviour has not been determined by a functional assessment interview and direct observation (Alter et al., 2008; Horner, 1994).

Functional Analyses involve manipulating the conditions under which a behaviour may occur to determine when a behaviour most frequently occurs. As the name suggests, a functional analysis involves conditions based on the functions of behaviour (sensory, escape, attention, tangible) where the behaviour is rewarded based on the condition being tested. If the behaviour occurs more frequently in a specific condition, then fulfilling that function is likely reinforcing for that particular behaviour, and likely to be causing that behaviour in real life (Alter et al., 2008; Horner, 1994). To get a better idea of the process, let’s consider what each of the conditions might look like:

Alone (Sensory) Condition: An alone condition is used to test if a behaviour is maintained by sensory reinforcement. If a behaviour persists at high rates when an individual is alone, they may likely be receiving some sensory input that is reinforcing for them. This is a sign that they may be engaging in the behaviour as a means to access sensory input.

Escape Condition: An escape condition is used to test if a behaviour is maintained by negative reinforcement or escape from something. If a behaviour persists at high rates when an individual is allowed to escape from something unwanted directly after engaging in the behaviour, this is a sign that they may be engaging in the behaviour as a means to escape.

Attention Condition: An attention condition is used to test if a behaviour is maintained by attention from others. If a behaviour persists at high rates when an individual is given attention directly after engaging in the behaviour, this is a sign that they may be engaging in the behaviour as a means to access attention.

Tangible Condition: A tangible condition is used to test if a behaviour is maintained by access to some activity or item. If a behaviour persists at high rates when an individual is given access to some activity or item directly after engaging in the behaviour, this is a sign that they may be engaging in the behaviour as a means to access some tangible reinforcer.

Typically, after inducing each of these conditions, the practitioner will graph the frequency of behaviour under each condition. Since functional analyses are typically used for complex behaviours, it is not uncommon for a behaviour to be maintained by multiple functions. For example, a child engaging in a tantrum in a classroom might be seeking both escape from the classroom environment and attention from the other students (Hanley et al., 2003).

Treatment Planning

After completing the FBA, the next step of behaviour treatment is to develop and implement a treatment plan based on the findings from the FBA. The treatment plan is designed with specific, measurable, and relevant goals that are tailored to the individual’s needs. These goals can pertain to modifying the frequency, intensity, and duration of the target behaviour. A specific timeline can also be outlined to monitor progress and evaluate whether the treatment is achieving the desired outcome for the individual. Based on the target behaviour, the clinician selects appropriate evidence-based interventions (Alter et al., 2008; Kern et al., 1994).

Implementation

Once the treatment plan is developed, the next phase is the implementation of the plan.

Behavioural treatment might occur in the natural environment of the individual, such as the home, school, or work, where the target behaviours occur. This ensures that the skills learned are relevant and can be generalized to various situations. To facilitate the transfer of skills to the natural environment, the clinician might also assign field trips or homework assignments. These assignments are carefully designed to allow the individual to practice new behaviours outside of therapy sessions (Ghaemmaghami at al., 2021; Latham & Heslin, 2003).

During implementation, the clinician assumes the role of a coach or teacher, providing guidance and support as the individual works to apply the treatment plan. This collaborative relationship ensures that the individual feels supported and confident in using the skills learned. Throughout the implementation phase, the clinician regularly reviews the individual’s progress to assess the effectiveness of the treatment. This involves discussing successes and challenges encountered during homework assignments or field trips, providing feedback, and making any necessary adjustments to the treatment plan (Latham & Heslin, 2003).

Outcome Assessment

The final phase of the behavioural treatment process is outcome assessment, which involves evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. Behaviour therapists will regularly evaluate whether the target behaviours have been reduced, increased, or modified as intended. To assess progress objectively, therapists will frequently re-administer the same self-report measures, self-monitoring tools, observations, and interviews that were used during the initial assessment phase. Using the same tools allows the therapist to compare and evaluate changes in the individual’s behaviour over time. Increasingly, technology is being integrated into this process through the use of mobile apps and digital platforms that support self-monitoring, making it easier for clients to track their behaviour consistently and for therapists to track treatment progress in real time (Areàn et al., 2016). Research has shown that therapists who actively engage in treatment monitoring increase the likelihood of success for their clients (Bear et al., 2022).

If the treatment is successful, the process concludes with the achievement of the desired behavioural changes. However, if progress is not being made, the therapist might need to reformulate the treatment plan. This might involve revisiting the antecedents or consequences of the behaviour to identify if additional factors are at play (Bear et al., 2022).

Behavioural Approaches

Having outlined the comprehensive process of behaviour treatment, we will now explore the specific behavioural therapy approaches that are implemented during the treatment process. These techniques are the core tools therapists use to modify behaviour and address the individual’s unique needs.

It is important to note that some behavioural interventions focus solely on introducing new skills or increasing the frequency of previously known skills. There are many types of intervention; this chapter will discuss some of the most common:

Contingency Management

Contingency management is a behavioural intervention grounded in the principles of operant conditioning. It involves modifying the consequences of a behaviour to encourage desirable actions and reduce maladaptive ones. Contingency management involves the reinforcement of desired behaviours and the withholding of incentives or rewards in response to undesired behaviours (Petry, 2011).

Contingency management can take many forms, of which the following are a few examples:

- Shaping: using contingency management to successfully shape a desired behaviour. This involves first rewarding any behaviour that approximates the desired behaviour; then, gradually reinforcing behaviour that more and more closely resembles the desired behaviour. An example of this is teaching someone how to do laundry – begin with rewarding them for sorting the clothes, then reward them for sorting the clothes and bringing it to the washing machine, and so on (Cihon, 2022).

- Time-out: a time-out can extinguish undesirable behaviour by removing the person temporarily from a situation in which that behaviour is reinforced. An example of this is removing a child that is disrupting the class from the room so that their behaviour is not being reinforced by the attention of classmates, which will hopefully extinguish the disruption (Tully & Hawes, 2023).

- Contracting: involves drawing up a contract with the client that specifies behaviours that are desired and undesired, and the consequences for engaging in or failing to engage in those behaviours (Edgemon et al., 2021).

- Premack Principle: this technique involves doing the behaviour you don’t want to do first, so the desirable behaviour is reinforced by allowing the individual to engage in a more attractive behaviour. An example of this is letting a child go play with their friends after they have first completed their homework (Herrod et al., 2023).

Test yourself!

Token Economies

Token economies are behavioural interventions that are grounded in operant conditioning. Token economics involve positively reinforcing desirable behaviour with “tokens” that can be exchanged for a variety of reinforcers, such as, food, games, or privileges (Mason et al., 2016).

To establish a token economy, it must be clear which behaviours are desired and will be reinforced. Further, the nature of the token, the reinforcer, and the reinforcement contingency must also be clearly identified. There are many aspects of token economies that are crucial in their effectiveness. First, the token needs to be given immediately after the desired behaviour occurs. Token economies also require good record keeping and consistency. If the tokens are not being given out consistently, the individual will quickly lose motivation to engage. Token economies also require a supervising adult that is observant and committed to the importance of the program (Mason et al., 2016).

An example of a token economy is children completing various chores for which they can earn stickers or checkmarks. The stickers or checkmarks can then be exchanged for rewards such as screen time or their favourite treat. Token economies are very practical for providing rewards to individuals as it is much easier to give a token as soon as the child cleans their room or completes a chore on the list than it might be to take the child to go see their favourite movie immediately (Mason et al., 2016). Token economies are also commonly used in residential in-patient populations.

Token economies are incredibly versatile and can be very effective as the desired behaviours and rewards are fully customizable to the goal of the client. It is very important that the rewards be desirable enough to motivate clients (Mason et al., 2016). Note that this might require changes in the reinforcer if the original loses some of its value to the individual.

Social Skills Training

Poor social skills can negatively impact interpersonal functioning and are often linked to conditions such as depression and anxiety (Segrin, 2000). To address these challenges, social skills training is used as a behavioural intervention to teach behaviours that improve interpersonal relationships, such as friendships, school, and workplace relationships. Social skills training often focuses on improving both verbal and nonverbal communication skills, appropriate emotional expression, empathy, manners, and assertiveness (Mikami et al., 2014). Social skills training is also useful for children with autism spectrum disorder (Alahmari et al., 2025), and ADHD (García-Castellar et al., 2025), who often have various social deficits.

Social skills training therapy typically incorporates role-play, where the therapist and client practice in-session role-plays, where the skills are rehearsed and practiced during the sessions. After practicing in sessions, clients are encouraged to apply their new skills in real-life situations. In the following session, clients and the therapist review the outcomes of the homework, where successes will be praised, and the difficulties will be addressed (Mikami et al., 2014).

Exposure Therapy

Exposure therapy is a behavioural intervention that involves exposing individuals to situations that are feared/avoided in a controlled and systematic way. Exposure therapy is grounded in the principles of classical conditioning and is often considered to be the gold standard therapy for anxiety disorders (Weisman & Rodebaugh, 2018). For example, meta-analytical research demonstrates that therapy including exposure is superior to therapy that does not include exposure in the treatment of anxiety and related disorders (e.g., PTSD, OCD; Parker et al., 2018).

The core premise of exposure therapy is that avoidance, while temporarily anxiety relieving, reinforces fear in the long term. By gradually facing these fears, individuals can learn that the feared stimulus or situation is not as dangerous as it seems and that their anxiety will naturally diminish over time through a process called extinction (Abramowitz et al., 2019).

Extinction occurs when the client confronts the CS in absence of the US, meaning that they do not feel threatened by the fearful stimulus anymore (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972). In the case of the child being afraid of the dog from the beginning of the chapter, extinction would involve safely interacting with dogs without being bitten. As the child repeatedly encounters the dog without harm, the association between the dog and fear weakens, and the dog is no longer perceived as a threat.

However, it would not make sense to just throw the child in the room alone with a dog, because that would not help the fear and could increase it. Rather than confronting fears head-on all at once, therapists use systematic desensitization in exposure therapy. Systematic desensitization involves starting with exposure to less fearful stimuli and progressing to more challenging stimuli in a controlled manner (Prayetno et al., 2020; Wolpe, 1958).

Systematic desensitization is guided by a fear hierarchy, which is a structured list of feared situations or stimuli, ranked from least to most anxiety-inducing. Fear hierarchies are produced by collaboration between the client and therapist to foster a sense of safety and confidence in the client, ensuring that no step feels overwhelming for them by the time it is reached (Blakey et al., 2019). Fear hierarchies allow clients to build self-efficacy as they gradually confront their fears (Prayetno et al., 2020). Table 2 illustrates an example of a fear hierarchy for a child with a fear of dogs.

Table 2 Example of a fear hierarchy for a child with a fear of dogs

| Stimulus | Fear Rating |

| Petting a dog off leash | 10 |

| Petting a dog on a leash | 9 |

| Stand next to a dog, but not touching it | 8 |

| Standing 5 feet away from a dog | 7 |

| Standing 10 feet away from a dog | 6 |

| Watching a dog from across the street | 4 |

| Hearing dog sounds (e.g., barking, panting) | 3 |

| Watching a video of a dog | 2 |

| Looking at a photo of a dog | 2 |

Exposure therapy can take several forms depending on the client’s needs and the nature of the fear. This can be done through in vivo exposure, imaginal exposure, interoceptive exposure, and virtual reality.

In vivo exposure: confronting the threatening stimuli in real life (Garcia-Palacios et al., 2001).

Imaginal exposure: confronting unwanted thoughts/imagined distress (Garcia-Palacios et al., 2001).

Interoreceptive exposure: provoking benign bodily sensations that trigger fear (Deacon et al., 2013).

Virtual reality exposure: confronting the threatening stimuli using virtual reality. This method of exposure is useful for situations that are difficult to recreate in real life (Garcia-Palacios et al., 2001).

Although it may seem that exposure therapy would make clients extremely uncomfortable or even worsen their anxiety, experiencing anxiety is actually the most important aspect of exposure therapy. Clients must experience the anxiety for them to be able to realize that the anxiety or situation is not as threatening as they originally thought. It is incredibly important for the individual to experience distress through this repeated exposure as it allows them to experience the activation and natural reduction of fear in the presence of feared stimuli (Abramowitz, 2013; Prayetno et al., 2020).

Exposure and Response Prevention

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is a specialized form of exposure therapy used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). ERP involves confronting feared situations, stimuli, or thoughts, while refraining from engaging in compulsive behaviours. ERP is grounded in an understanding that compulsions offer temporary relief but perpetuate the cycle of anxiety and obsession. Therefore, ERP aims to help clients recognize that they can manage their anxiety and distress without resorting to compulsive behaviours.

Like exposure therapy, ERP exposures are guided by systematic desensitization through the creation of a fear hierarchy (Law & Boisseau, 2019). It is typical for the therapist to model how to do the exposure first. Table 3 provides an example of a fear hierarchy for an individual with OCD of the contamination subtype.

| Situation/Stimuli/Thoughts | Fear Rating |

| Using a public restroom without washing hands afterward | 10 |

| Picking up trash in a public area without washing hands afterward | 9 |

| Shaking hands with a stranger and not washing hands afterward | 8 |

| Touching a door handle in a busy public space without washing hands afterward | 7 |

| Handling money | 5 |

| Holding onto a pole or handrail on public transportation | 4 |

| Touching a grocery cart handle without sanitizing beforehand | 3 |

| Touching a doorknob at home without washing hands afterward | 2 |

Relaxation Training

Relaxation training encompasses a variety of techniques designed to help clients reduce physiological and emotional tension. Relaxation training techniques can be used as the primary treatment approach or alongside other therapeutic interventions. Relaxation training is highly effective in reducing anxiety and distress (Hamdani et al., 2022). Examples of relaxation training techniques involve calm diaphragmatic breathing, guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, yoga, and meditation (Hamdani et al., 2022).

Diaphragmatic breathing: involves slow, controlled breaths that engage the diaphragm, reducing heart rate and promoting a sense of relaxation. Clients are taught to focus on the breath as a grounding technique (Hopper et al., 2019).

Guided imagery: involves visualizing calm and peaceful settings in place of distressing thoughts or memories. It is encouraged that clients fully immerse their mind in the imagery by focusing on sensory and contextual details, redirecting attention and encouraging relaxation (Toussaint et al., 2021).

Progressive muscle relaxation: involves tensing and relaxing muscle groups and focusing on the sensations of relaxation that are achieved from this (McCallie et al., 2006).

Behavioural Activation

Behavioural activation is an additional form of behavioural therapy that is used primarily in treatment for depression to plan and encourage engagement in rewarding and pleasurable activities. Behavioural activation is centered around the idea that dissatisfying daily activities, such as withdrawal and inactivity, can result in depression, and also maintain or reinforce it. So, by helping clients identify and schedule purposeful and adaptive activities into their daily routines, behavioural activation aims to break this negative cycle and bring pleasure back into the client’s life (Cuijpers et al., 2007).

After scheduling these activities into the clients’ daily routines, the next step is activity monitoring. Clients must be proactive by monitoring their behaviour, and recording their daily activities. Clients are encouraged to recognize their mood before and after completing the activities. By comparing these mood ratings, they can observe the connection between engaging in specific activities and changes in their mood. The goal is for clients to notice improvements in mood or a sense of accomplishment after engaging in the activities, which can encourage them to continue participating in these activities (Chartier & Provencher, 2013; Hopko et al., 2003).

Behavioural activation is typically a short-term intervention that can be used on its own or with other interventions, and it can be very effective (Chartier & Provencher, 2013).

Strengths and Criticisms of Behavioural Approaches

Strengths of Behavioural Approaches

Empirically supported: Behavioural interventions are first-line treatments for many mild-moderate psychological disorders, and work better than some other forms of treatment for the same conditions.

Efficient: Behavioural interventions are efficient as they are present-focused. Behavioural interventions do not require going into client history in too much detail, and clinical improvement can be found in just a few weeks.

Wide applicability and generalizability: Behavioural interventions can be accessed by clients with varied cognitive and verbal abilities. Behavioural interventions are also not focused on understanding abstract concepts or doing a lot of work with thoughts that can be hard for some clients to grasp. Therefore, individuals with cognitive impairments can still benefit from these interventions. Because some behavioural interventions might only require a few sessions, they may be more accessible for people with financial limitations. Further, as some aspects of behavioural interventions can be completed by the individual, it can encourage the individual to be an active agent in their own behaviour change

It is important to note that there are groups that will benefit more from these behavioural interventions than others. For instance, those who have the ability to keep records and self-monitor, those who have support from parents, teachers, others, those who have insight and are willing to confront threatening stimuli, as well as those who are able to dedicate time and energy to practice will benefit most from behavioural interventions (Huppert et al., 2006).

Criticisms of Behavioural Approaches

Ineffective for severe psychopathology: Behavioural interventions are ineffective for psychosis, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, severe depression. However, they might still be a component of a larger treatment plan. For instance, although bipolar disorder is primarily treated with medication, behavioural approaches can support clients by helping them manage distress, adhere to treatment, and improve daily functioning (Özdel et al., 2021).

Skill-based treatment: Benefits of the treatment are tied to the client’s effort. This can be very hard for individuals who have less motivation, such as those with depression (Bi et al., 2022).

Behavioural terminology discomforting: Behavioural interventions have been criticized for involving “cold” therapists who do not foster “inner growth,” however, behavioural interventions can still be done with a warm, empathic approach with unconditional positive regard toward clients.

Check in

Alice is a 17 year old girl who enjoys spending time with friends, loves retro movies, and is a competitive swimmer. Alice was recently diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder. Alice has strict routines around mealtimes, including specific orders and methods for washing and drying utensils and dishes before serving food. Alice shared with her clinical psychologist that these behaviours make her feel safe; otherwise everything feels too contaminated for her to eat. These behaviours have been causing distress for Alice because she feels unable to eat at school or anywhere other than home. This is particularly challenging for Alice as she wants to attend more long-distance swim meets. To get some help with this problem, Alice will continue to see a clinical psychologist.

- How could learning theory be applied to explain Alice’s behaviour? (LO2)

- What steps might be involved in the assessment of Alice’s behaviour? (LO3)

- What treatment options might be appropriate for Alice? Consider the pros and cons of each approach you propose. (LO4)

- What might be the strengths or drawbacks of using a behavioural approach to create meaningful change for Alice? (LO5)

- Imagine you are the clinical psychologist treating Alice. How does the history of behavioural techniques inform your approach, and why is this understanding important? (LO1)

Test yourself!

Media Attributions

- Classical conditioning © Salehi.s adapted by Valerie hedges is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Operant conditioning © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- ABC visual © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- sticker chart is licensed under a Public Domain license

- dog © U.S. Army is licensed under a Public Domain license

- friends © William Morris is licensed under a Public Domain license

The process by which individuals come to associate a known stimulus with a previously neutral stimulus, causing the neutral stimulus to now elicit a response.

A stimulus that elicits a response prior to any conditioning.

A behavioural response to the unconditioned stimulus.

A stimulus that comes to elicit a response after being paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

The behavioural response that develops in response to the conditioned stimulus over time (as it is paired with the unconditioned stimulus).

Adding a stimulus to increase the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future.

Removing a stimulus to increase the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future.

Adding a stimulus to decrease the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future.

Removing a stimulus to decrease the likelihood of a behaviour occurring in the future.

An operational definition describes the behaviour in a way that is observable and measurable.

What occurs directly before the behaviour.

The observable and measurable action taken by the individual.

What happens directly after the behaviour.

Events that make it more likely that a behaviour will occur.

Feeling a desired sensory input.

Avoiding an item, activity, sensation, person, etc.

Receiving attention from another person.

Gaining access to a desired item or activity.

first rewarding any behaviour that approximates the desired behaviour; then, gradually reinforcing behaviour that more and more closely resembles the desired behaviour.

Temporarily removing a person from a situation.

Drawing up a contract with the client that specifies behaviours that are desired and undesired, and the consequences for engaging in or failing to engage in those behaviours.

Doing the behaviour you don’t want to do first, so the desirable behaviour is reinforced by allowing the individual to engage in a more attractive behaviour.

Token economics involve positively reinforcing desirable behaviour with “tokens” that can be exchanged for a variety of reinforcers, such as, food, games, or privileges.

Refers to the gradual weakening and disappearance of a learned behavior when it is no longer reinforced.

Involves starting with exposure to less fearful stimuli and progressing to more challenging stimuli in a controlled manner.

A structured list of feared situations or stimuli, ranked from least to most anxiety-inducing.

Confronting the threatening stimuli in real life.

Confronting unwanted thoughts/imagined distress.

Provoking benign bodily sensations that trigger fear.

Confronting the threatening stimuli using virtual reality.

ERP involves confronting feared situations, stimuli, or thoughts, while refraining from engaging in compulsive behaviours.

Involves slow, controlled breaths that engage the diaphragm, reducing heart rate and promoting a sense of relaxation.

involves visualizing calm and peaceful settings in place of distressing thoughts or memories.

Involves tensing and relaxing muscle groups and focusing on the sensations of relaxation that are achieved from this.