6 Proactive Approaches to Well-Being: The Role of Prevention in Clinical Psychology

William Langille and Haley C.R. Bernusky

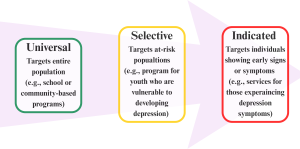

Imagine you’re a practicing clinical psychologist interested in depression in youth and emerging adults. You have a caseload of teens burdened with depression that had taken root long before they ever stepped foot in your office, the waitlist at your clinic grows each month, and you become increasingly concerned with how many young people need professional help. You see as many clients as you can, helping individuals gain the skills they need to deal with depressive symptoms, but you wonder how you could help them before they experience these symptoms. In other words, you become highly invested in prevention methods in clinical psychology, and you launch a project in local middle and high schools running Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)-based group sessions designed for students at risk of developing depression. You teach students skills for how to identify their unhelpful automatic thoughts and help build coping skills, practicing cognitive reframing techniques. After the trial ends, you conduct post-intervention follow-up surveys with the same students and compare their results to their pre-intervention scores. The results are in, and your hard work has made a difference: the students had significantly lower rates of depression and were more resilient than before their involvement in your workshops! This one quick example illustrates the power of prevention in clinical psychology – it’s not just about pulling people out of the deep end when they’re already drowning, but teaching them how to swim before they ever fall into the water in the first place. In this chapter, we review a range of universal, targeted (selective) and indicated evidence-based approaches to prevention of mental health disorders, including anxiety and depression, suicide, substance use, eating disorders, bullying, and sexual violence. We review research on effective programs throughout, and conclude with an example of prevention programming gone wrong.

- Explain the general origins and history of prevention and prevention programming.

- Distinguish between prevention and intervention approaches, including types of prevention.

- Discuss clinical prevention programming in the Canadian context (e.g., substance use prevention, bullying, and sexual violence prevention).

- Describe what “evidence-based” prevention means and describe its importance.

What does “prevention” mean in the context of clinical psychology?

Until recent decades, prevention was not a significant focus in clinical psychology. Historically, clinical psychology was primarily concerned with understanding psychology at the individual level, including the diagnosis and treatment of individual experiences of mental disorders (Lee & Hunsley, 2018). The major focus of clinical psychology has long revolved around approaches to clinical intervention, which were often limited to individuals and their direct relations/systems (i.e., individual, couples, and family therapies). The field of community psychology was vital for the development of prevention approaches in clinical psychology. Community psychology approaches focus on the reciprocal relationships between the community and its constituent members and has a long history of implementing services for populations who are known to be vulnerable (Trickett, 2009). In the 1960s, community psychologists began questioning clinical psychology’s emphasis on individual interventions and treatments, providing evidence supporting the benefits of community-based prevention (Hasford & Prilleltensky, 2019). More recently, the field of clinical psychology has increased its interest in broader-reaching group-based prevention programs. This shift toward prevention is due in large part to the disparity in the number of people facing mental health challenges needing support and the amount of trained mental health professionals available to assist them. Some have even suggested that there will never be enough mental health professionals to adequately combat our high rates of mental illnesses (Albee, 1990; Hasford & Prilleltensky, 2019), highlighting the need for clinical psychology’s more contemporary focus on prevention.

You might now be wondering what prevention and intervention actually are and how they differ from one another. As with most concepts in psychology, the distinctions are not black-and-white. Rather, while prevention and intervention are two different concepts, they may both be considered to be shades of grey along a continuum (Purgato et al., 2020). In general, the difference is that prevention methods aim to reduce risk in those who are vulnerable but do not yet meet diagnostic criteria for mental health or substance use disorders with the goal of stopping or delaying the onset and/or severity of disorders and their associated symptoms. In contrast, intervention programs target those who do meet diagnostic criteria to therapeutically address concerns related to their disorders (Purgato et al., 2020). In the sections that follow, we will see how “prevention” is itself not a singular approach but a broad term that encompasses many approaches, the nuances of which will be discussed in turn.

There were three originally proposed levels of prevention which came from the epidemiology and public health fields: 1) primary prevention, which aims to prevent disorders from occurring; 2) secondary prevention, which focuses on shortening the duration of disorders, and 3) tertiary prevention, which seeks to prevent disabilities from forming as a result of existing disorders (Public Health Agency of Canada, n.d.). Since then, the United States Institute of Medicine (1994) has proposed a different conceptualization of prevention approaches, again with three forms: universal, targeted (selective), and indicated.

Universal prevention approaches in clinical psychology are designed to prevent mental health and substance use issues for entire populations or all people within a particular setting or location like a specific province, school, or workplace (Hasford & Prilleltensky, 2019). Universal methods often address key factors already known to affect behaviours in the general population, such as teaching skills for drug/substance refusal, reducing harmful and/or biased social norms, and teaching methods for parent-children communication about substances, with the aims of reducing the chance of developing risk factors and increasing resiliency broadly (Institute of Medicine, 1994; McVey & Antonini, 2016). If you attended public school as a child, it is very likely that you participated in some sort of universal prevention programming, such as a bullying prevention program that was given to your whole grade or class, regardless of whether or not each student was involved in bullying at that time.

Targeted or selective prevention approaches aim to target individuals who are at a higher risk of developing disorders or known risk factors for developing disorders (Hasford & Prilleltensky, 2019). These programs can target both external factors, such as family difficulties, and internal factors, like personality risk factors or vulnerabilities to internalizing disorders like anxiety or depression. An example of selective prevention would be a program specifically designed for children with a family history of mental health and substance use problems, since a family history is a known risk factor for the child’s own mental health (Bröning et al., 2012). Lastly, indicated prevention approaches in clinical psychology focus on people who could already be experiencing early signs or symptoms of a mental health or substance use disorder but do not yet meet the full criteria for a clinical diagnosis (Hasford & Prilleltensky, 2019). Indicated programs aim to prevent the progression of subthreshold symptoms, an example of which could be a workshop designed to help high school students displaying early signs of depression, based on, say, routine screening by the school counsellor. Rather than waiting to intervene once disorders have fully developed, such a program would aim to educate high-risk students early on. For example, such a program might use skills from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for depression to help students learn to cope with low mood in a group-based setting (Ssegonja et al., 2019). The prevention approach just described, however, certainly sounds a lot like an intervention! In practice, the line between indicated prevention and early intervention is blurry. In terms of the previous levels of prevention discussed, this approach may also be considered a secondary prevention approach as it aims to prevent the worsening of existing symptoms rather than focusing solely on preventing the emergence of any symptoms at all.

Given that prevention measures generally aim to reach people before disorders can develop or worsen (i.e., primary prevention), many preventions are targeted toward children and adolescents. This makes sense in clinical psychology especially, as most psychopathology develops during or before adolescence (Costello et al., 2011). Therefore, while we have generally taken a lifespan approach to this chapter by discussing preventions applicable to various age groups, including emerging and older adults, there is a greater focus on primary preventions tailored to youth. Prevention approaches provide a means of pre-emptively addressing many mental health concerns and disorders faced across society, however, their designs, applications, and approaches can vary depending on the disorder or concern they address.

Test Yourself!

How do we know if a program works?

Before providing some examples of prevention programs, it is critical to first highlight the importance of research: clinical psychological scientists want to make sure the programs they are offering actually have the intended beneficial outcomes. Relative to other mental health care professionals, clinical psychologists are well-suited for program evaluation given their extensive research training.

One of the best ways to determine the efficacy of a prevention program is to assess effect sizes obtained from meta-analytic reviews of randomized-controlled trials comparing outcomes across intervention and control groups. In clinical psychology, effect sizes are often presented in terms of Cohen’s d or Hedges’ g, both of which follow the same guidelines for interpreting the magnitude of effects: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, and 0.8 = large (Cohen, 1988; 1992). Historically, small effects in psychological research have been rebuffed as marginally important, but in recent years, perspectives have begun to shift. Evidence suggests that small effects of clinical preventions and interventions are typical, with studies (including meta-analyses) often overestimating the magnitude of effects (Bartoš et al., 2023; Cuijpers et al., 2010). If small effects are the norm in psychological research and the corresponding outcomes show improvement, then the evidence suggests that small effects can have meaningful impacts at the population level (Barkham, 2023). All this is to say that smaller effects should not be dismissed, especially in the context of broad-reaching programming aimed at preventing or delaying the onset of common mental disorders. This framework is important to have in mind as we go through examples of prevention programs in the next section.

Prevention of Common Internalizing Disorders and Suicide

While mental health challenges may arise in those of all ages and across all stages of life (Canadian Mental Health Association [CMHA], 2023), certain developmental periods are riskier than others for the onset of certain mental health problems. For example, individuals often experience the onset of anxiety and depression during the vulnerable developmental stages of adolescence and emerging adulthood (Statistics Canada, 2024, September). In Canada, youth aged 16-24 years old have the highest rates of anxiety at 40.3% and the second highest rates of depression at 32.3% of people reporting symptoms, exceeded only by those aged 25-35 years at 33.8% (CMHA, 2023). Since these internalizing disorders pose risk for early onset, many prevention programs are designed for school-aged youth and adolescents, in line with a primary prevention approach of reaching individuals before disorders can occur.

Prevention of Internalizing Disorders

Many youth-focused interventions for anxiety and depression are universal prevention approaches with the aim of establishing healthy habits and behaviours before negative or harmful behaviours can set in (Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). These approaches focus on general mental health education, promoting resilience, and teaching basic coping skills such as mindfulness, friendship skills, and stress management techniques (Barrett & Turner, 2001; Gillham et al., 2007; Kendall, 1994; Rose et al., 2014). Schools are a useful setting for implementing wide-reaching prevention programming as the majority of youth attend school regularly, they often have established relationships with trusted adults at school who provide the programming, and sometimes schools already have existing connections to mental health services for their students to engage with, presenting a cost-effective option (Masia-Warner et al., 2006; Merry et al., 2012; Rickwood et al., 2007; Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). Other youth-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression are selective or targeted in that they are delivered to students who have relevant risk factors for internalizing disorders such as low self-esteem, interpersonal skills deficits, past traumas, or family histories of mental health problems (Blanco et al., 2014). Selective prevention programs often take a deeper dive into providing more specific techniques from evidence-based intervention approaches shown to be effective for targeting the specific needs of the group in question. An example would be a program that teaches skills based in the principles of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) to those at risk for developing depression to help these targeted students to gain awareness of their maladaptive/negative thought patterns, which, in turn, may influence both their feelings and behaviours (Brunwasser & Garber, 2016).

Recently, Werner-Seidler et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of 118 randomized-controlled trials involving nearly 46,000 youth and adolescents to examine the efficacy of various school-based programs for preventing or delaying the onset of anxiety and depression symptoms in this vulnerable population. Their results showed that prevention measures had small but significant between-group effects on reducing anxiety (Hedge’s g = 0.18) and depression (g = 0.21) symptoms immediately post-intervention, which stayed mostly consistent over short- (0-6 months), medium- (>6-12 months), and long-term (>12 months) follow-up intervals (Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). Similarly, Brunwasser and Garber’s (2016) meta-analysis on school-based depression prevention programs revealed small but significant effects. In the depression literature, evidence suggests that targeted or indicated school-based programs for preventing depression in youth produced better short- and long-term outcomes compared to universally delivered programs (Brunwasser & Garber, 2016; Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). For anxiety, however, the evidence is less clear: some research shows mixed or no statistically significant differences in the effectiveness of school-based targeted vs. indicated vs. universal approaches for preventing or reducing anxiety in youth (Lau & Rapee, 2011; Moreno-Peral et al., 2017; Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). Although results may vary by approach, these results suggest that school-based programs are effective at the population level for preventing and/or delaying the onset of anxiety and depression symptoms in youth.

Suicide Prevention

Suicide risk persists across the lifespan but is higher in certain populations. For instance, in 2019, completed suicide rates were higher for Canadian males than females of all ages, with those aged 50-64 years at highest risk overall (25.9 males and 8.4 females per 100,000), while non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts were more common among females, especially young females (Statistics Canada, 2023, January). Others at high risk for suicide and related behaviours include veterans: veterans are 1.4-1.9 times more likely to die by suicide compared to their peers in the general population (Boulos, 2022; Simkus et al., 2019). Indigenous (i.e., First Nations, Métis, Inuit) individuals face three times higher risk of suicide than non-Indigenous people (Kumar & Tjepkema, 2019), and members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community also have elevated risk relative to heterosexual and cisgender people (Haas et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2023). The risk of suicide is also related to psychopathology like depression (Favril et al., 2022; Hawton et al., 2013; Masango et al., 2008), adverse life events like relationship or family conflict (Favril et al., 2022), and disadvantages such as lower education levels or socioeconomic status (Beautrais et al., 2000). Many of these risk factors intersect, amplifying risk (Beautrais et al., 2000; Masango et al., 2008).

Suicide prevention approaches may target specific populations, tailored for different age groups (e.g., youth or older adults) or by culture (e.g., programs specifically for Indigenous populations). Evidence-based prevention strategies for suicide may include restricting access to lethal means, enhancing education programs to reduce stigma, and raising awareness of risks and supports (Brann et al., 2021; Hofstra et al., 2020; Zalsman et al., 2016). While the ultimate goal of these programs is typically to prevent suicide deaths, they are also effective in reducing psychological distress (g = 0.16) and in raising awareness (g = 0.72; Brann et al., 2021). Effective prevention efforts often take a public health approach to empower people and their communities to address suicide collaboratively by combining training, education and resources (Nichols & Googoo, 2023).

Nova Scotia’s program Communities Addressing Suicide Together (CAST) exemplifies this approach, using evidence-based practices (Canadian Mental Health Association: Nova Scotia Division, 2025; Health Canada, 2015; World Health Organization [WHO], 2014b) to improve community mental health and suicide resources (Nichols & Googoo, 2023). It offers specialized programming like the Indigenous Peer Support and Education group, effective for stress management, reducing anxiety and depression, and increasing self-care among this high-risk population (Nichols & Googoo, 2023). CAST offers programs for others at greater risk for suicide as well, such as middle-aged men, focused on improving their mental health literacy and encouraging help-seeking behaviours through group-based interventions (Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2016). One such initiative is CAST’s Meaning-Centered Men’s Group which has shown success in reducing depression and preventing suicide while increasing life satisfaction and resiliency in men transitioning to retirement (Heisel et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Preventing common mental health disorders and suicide requires early, targeted, and culturally responsive interventions. School-based programs help equip youth with tools to build resilience and delay the onset of anxiety and depression, and while universal programs benefit people broadly, targeted and indicated prevention programs tailored to specific at-risk groups often yield greater results by effectively addressing unique risk factors. Suicide prevention efforts similarly must consider diverse high-risk populations, with programs aimed at reducing lethality and stigma and increasing supports. Community-based public health initiatives like Nova Scotia’s CAST program illustrate the benefits of culturally sensitive, evidence-based approaches that align with global best practices to contribute to meaningful differences in our local Atlantic Canadian communities. The cumulative impact of preventative programs can be substantial at the population level, fostering mental wellbeing and strengthening support systems for those of diverse identities and across various developmental stages.

Spotlight on: Eating Disorder Prevention

The term “eating disorders” (EDs) is a general one that encompasses various specific disorders, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). EDs pose a significant health risk, as they are the mental disorders with the highest mortality rate of 10-15% (National Initiative for Eating Disorders [NIED], 2024). EDs effect an estimated 1.7 to 2.7 million Canadians, with more than half being youth (51.9%; NIED, 2024). EDs may impact anyone: young women report EDs at significantly higher rates than men, especially anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Galmiche et al., 2019; NIED, 2024; Taylor et al., 2017), however, young males and individuals of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community are also at risk of experiencing EDs. Approximately 13% of all women experience disordered eating by age 20, with the peak age of onset ranging from 16-20 years across disorders (Stice et al., 2013; 2021). ED risk factors include being female, the societal pressure of thin beauty standards, pursuing those thin ideals, body dissatisfaction, and deficits in social support (Allen et al., 2014; Dakanalis et al., 2017; Jacobi et al., 2011; Rohde et al., 2015; Stice et al., 2021; The McKnight Investigators, 2003). Many approaches to ED prevention are primary in that they are designed for implementation with youth to address the issue before it develops. These programs are often dissonance-based, meaning that they aim to emphasize the psychological discomfort that arises when there is inconsistency between one’s beliefs (e.g., importance of the thin body ideal) and one’s actions, learning to challenge their unhelpful beliefs (Maas et al., 2023). Some programs are cognitive behavioural therapy or lifestyle modification-based, and others are based on psychoeducation or family-based prevention (Stice et al., 2021).

A recent meta-analysis of 15 reports on ED prevention programs found that, on average, the programs significantly reduced or delayed ED onset (OR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.09, 2.46], t = 2.54, p = .020), with lifestyle modification and dissonance-based approaches showing the greatest effects (Stice et al., 2021). A dissonance program, The Body Project, had the most consistent effects on preventing ED onset (Stice et al., 2021), and significantly reduced ED risk in samples from the United States, United Kingdom, Brazil, Mexico, China, and Sweden (Ghaderi et al., 2020; Stice et al., 2008, 2019, 2020), the effects of which were still apparent at 4-year follow up (Stice et al., 2021). Notably, these reduction effects were greatest when peers of similar age and sex facilitated the intervention, emphasizing the importance of peer support in effective ED prevention (Stice et al., 2021). Several Canadian universities have adopted The Body Project and offer peer-led groups, including the University of Manitoba (2024), Toronto Metropolitan University (2024), and McGill University (2024). Originally designed for women, The Body Project now includes sessions adapted for men, offering groups focused on eating pathology, internal and external pressures to be thin, and the costs of striving for thin ideals through verbal, behavioural, and written exercises (Shaw & Stice, 2016). The Body Project helps participants develop a more balanced image of themselves, with participants reporting increased body positivity and empowerment post-intervention (Shaw & Stice, 2016). Overall, The Body Project has considerable preventative potential with a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) effect size of 8-11, meaning that giving the program to 8-11 people prevents the onset of one instance of an eating disorder that would likely have occurred in absence of the intervention (Stice et al., 2021).

Spotlight on: Canadian Substance Use Prevention

Substance use is widespread in Canada. Among students in grades 7-12, 39% reported alcohol and 18% reported cannabis use in the past year (Health Canada, 2024), with even higher rates among emerging adults aged 20-24 years: 84% for alcohol and 45% for cannabis (Health Canada, 2023). Interestingly, in 2019, Nova Scotia had the highest provincial prevalence rate of past-year cannabis use at 33% (Health Canada, 2023). Substance use is also linked to harms: of those reporting past-year alcohol and drug use (i.e., cannabis and illegal drugs), 21% and 5% experienced at least one substance-related harm, equating to 4.8 and 1.1 million Canadians, respectively (Health Canada, 2023). These high rates of substance use and related risk of harms underscore the importance of early interventions to prevent substance use onset among Canadian youth.

Prominent substance use researchers across Canada (many of whom are clinical psychologists) have collaborated to develop early, effective substance use prevention programs. Building on evidence linking certain personality traits to increased risk for substance misuse (i.e., anxiety sensitivity, hopelessness, impulsivity, sensation seeking; Castellanos-Ryan & Conrod, 2012; Conrod, 2016; Conrod et al., 2000), the PreVenture program was developed, a brief personality-targeted substance misuse prevention program for adolescents (Conrod et al., 2010; PreVenture, 2024). Through two 90-minute manualized group sessions rooted in the principles of cognitive-behavioural and motivational enhancement therapies, PreVenture teaches students coping skills and how to set goals and channel their personality to achieve them (Conrod, 2016; Edalati & Conrod, 2019; PreVenture, 2024), effectively reducing substance use risk by ~50% and reducing the risk of anxiety and depression by ~25% among adolescents (Conrod et al., 2006, 2011, 2013; Edalati & Conrod, 2019; O’Leary-Barrett et al., 2016). Given PreVenture’s success, a range of other Venture substance misuse prevention programs have been developed (Conrod Venture Lab, 2024). UniVenture is an adaptation of PreVenture designed to target the wellbeing and substance use risks of emerging adult university students (Conrod et al., 2022; UniVenture, 2023). Other adaptations have been developed for Indigenous youth (Mushquash et al., 2010, 2014, 2020), PsyVenture aims to prevent cannabis use in youth at-risk for psychosis, and virtual feasibility studies are testing the utility of Venture programming delivered entirely online (Conrod Venture Lab, 2024).

Preventing Violence and Promoting Healthy Relationships

Violence prevention and healthy relationship promotion are important areas of clinical psychology due to their relevance across the lifespan and implications with psychopathology. In this section, we first discuss bullying prevention, focusing on children and adolescents, followed by an overview of sexual violence prevention approaches, with a focus on emerging adults and adulthood.

Bullying Prevention

Bullying is a problem in Canada that occurs across contexts, including schools, sports teams, online, and even workplaces. Nationally representative research with Canadian youth in grades 6-10 indicates that approximately 1 in 3 girls and 1 in 4 boys are bullied regularly (Craig et al., 2020). Newer research including more diverse samples also indicates that transgender and gender diverse youth are disproportionately impacted by bullying, affecting approximately 1 in 2 gender diverse young Canadians (Lambe et al., 2025). Aggressors may take various approaches, including more traditional (e.g., physical, verbal, psychological) and more modern (e.g., cyber) forms of bullying (Farrington & Baldry, 2010). Indirect forms of bullying, like being left out on purpose or being called mean names, are more common than more direct forms, like physical fighting (Lambe et al., 2025). Bullying is associated with a range of negative outcomes, including increased anxiety, depression, and poor academic performance in children and adolescents (Armitage, 2021; Halliday et al., 2021). Given the high rates of bullying among Canadian youth in school environments, many bullying prevention approaches leverage the existing infrastructure of school systems to access a broad range of students on both sides of the bullying experience.

Many bullying prevention approaches are universal in nature, providing whole classes, grades, or schools with antibullying education and resources. Universal prevention approaches focus on teaching empathy and increasing communication, interpersonal, and emotion regulation skills (Bradshaw, 2015; Gaffney et al., 2019). In other words, these approaches teach healthy relationship skills that are incompatible with bullying behaviours. Selective or targeted approaches are often viewed as a “next step” in bullying prevention, often being implemented with select smaller groups of individuals who did not gain the necessary skills, education, or behavioural modifications from universal approaches (Bradshaw, 2015). These programs might address individual risk factors for bullying, including high impulsivity, low empathy, and histories of aggressive behaviours (Farrington & Baldry, 2010).

A recent meta-analysis of 100 studies on school-based bullying preventions reported that these programs are effective for significantly reducing both bullying perpetration (random effects OR = 1.309, 95% CI [1.24, 1.38], z = 9.88, p < 0.001) and victimization (random effects OR = 1.244, 95% CI [1.19, 1.31], z = 8.92, p < 0.001; Gaffney et al., 2019). These results suggest that overall, anti-bullying prevention programs reduce bullying perpetration in schools by ~19–20% and reduce bullying victimization by ~15–16% (Gaffney et al., 2019). One example of a Canadian evidence-based bullying and violence prevention program designed for universal school-wide implementation is WITS: Walk away, Ignore, Talk it out, Seek help. WITS was developed and evaluated by researchers at the University of Victoria and the University of Alberta (Hoglund et al., 2012; Leadbeater et al., 2003; Leadbeater & Sukhawathanakul, 2011; WITS, n.d.b.). The name itself consists of evidence-based strategies effective for helping youth deal with peer conflict (Hoglund et al., 2012, Olweus, 2005). WITS is designed for children aged 4-12 years, and it involves teacher-led activities aimed at addressing multiple components of bullying, including discussing peer conflict, promoting social competence and pro-social behaviours, and reducing risks for victimization (Hoglund et al., 2012; Leadbeater & Sukhawathanakul, 2011). Program content is delivered in monthly storybook-based lessons with activities included to increase youths’ awareness of peer conflict and bullying, teach conflict resolution skills, and increase bystander intervention (Leadbeater et al., 2003; Leadbeater & Sukhawathanakul, 2011). Schools that have implemented WITS report significant reductions in peer victimization in the elementary years, including physical (d = .20) and relational (d =.17) bullying, and report improved social competence compared to non-WITS schools (d = .20; Hoglund et al., 2012). Additional programming and research, however, is needed for bullying prevention targeting middle and high school youth. The bullying prevention program has been widely adopted, reaching over 1,400 schools throughout all 10 Canadian provinces and impacting more than 200,000 youth (WITS, n.d.a.). Given the prevalence of bullying in Canada, prevention is an important and promising approach for promoting healthy relationships in Canadian youth and adults alike.

Sexual Violence Prevention

Sexual violence is a broad term that encompasses unwanted sexual behaviours, including physical assault, abuse, touching, harassment, and online acts such as sharing unsolicited explicit photos (Government of Canada, 2024; WHO, 2014a). When considering reported rates of sexual violence, it is important to note that they only represent cases disclosed to the authorities, with many incidents going unreported, suggesting that the true prevalence may be much higher (Ending Violence Association of Canada, 2023, May). 1 in 10 Canadians report experiencing sexual abuse before age 15 years (Statistics Canada, 2022, December), however, victimization rates differ across sex and gender. For instance, in Canada, ~30% of women aged 15 years and older – equivalent to 4.7 million women – have reported being sexually assaulted (Cotter & Savage, 2019), and women aged 15-35 years report higher rates of sexual violence compared to men and older women (Cotter & Savage, 2019; Government of Canada, 2024). Men also experience sexual violence, however, primarily in their younger years, with 1 in 5 men aged 15-24 years reporting victimization (Cotter & Savage, 2019). Furthermore, members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community experience disproportionately higher rates of sexual violence compared to non-2SLGBTQIA+ peers (Cotter & Savage, 2019; Jaffray, 2020). Certain environments also pose increased risks for sexual violence, including workplaces, some public spaces, and college and university campuses (Burczycka, 2020; Cotter & Savage, 2019). Across Canada, ~71% of post-secondary students reported being a victim of, or witness to, unwanted sexual behaviours, such as verbal comments and physical actions (Burczycka, 2020). Of those who witnessed unwanted sexual behaviours, 91% of women and 92% of men did not attempt to intervene or seek help (Burczycka, 2020). Risk factors for perpetrating sexual violence include excessive substance use, male sex, risky sexual behaviours, and violent sexual beliefs or cognitions, such as perceived peer approval of forced sex, while risk factors for sexual violence victimization include female sex, marginalized identities, and lower socio-economic status (Bonar et al., 2022).

On college and university campuses, sexual violence prevention programs tend to be universally delivered and focus on educating emerging adults on consent, rape myths, substance use, and raising awareness of bystander intervention (Bonar et al., 2022; DeGue et al., 2014; Mujal et al., 2021). There are several approaches to sexual violence prevention, including bystander intervention training and psychosocial programs, however, and little research has compared the effectiveness of these different sexual violence prevention approaches. The few meta-analyses conducted offer mixed results; but, in general, longer interventions tend to be more effective than shorter interventions (DeGue et al., 2014), and bystander intervention training programs have shown promise (Mujal et al., 2021). These programs teach about consent and provide training on techniques for safely intervening in situations where violence may occur and for supporting victims (Banyard et al., 2009). The program with the largest evidence base is Bringing in the Bystander, which showed improved bystander behaviours for both friends and strangers (Senn & Forrest, 2016), increased bystander efficacy and intent to help (Cares et al., 2015; Moynihan et al., 2010), and decreased rape-myth acceptance (Banyard et al., 2009; Mujal et al., 2021). The program exists in different forms, including 90-minute and 4.5-hour versions, both of which lead students through potential responsibilities of bystanders to violent events, using real stories to describe intervention strategies and teach how to notice when peers need help (Banyard et al., 2009). While the program was developed in the United States, Bringing in the Bystander has been adapted for Canadian emerging adults, including at the University of Windsor (Senn & Forrest, 2016). Nova Scotia also has a similar prevention program called Waves of Change (St. Francis Xavier University, 2025) that is in the initial phases of development in building its evidence base. Created by the Antigonish Women’s Resource Centre and Sexual Assault Services Association in collaboration with the Nova Scotia Department of Advanced Education, Waves of Change is a peer-led, bystander intervention program that is implemented with first-year university students across Nova Scotia. Waves of Change seeks to educate and prevent sexual violence by breaking down harmful norms or beliefs and increasing sexual violence awareness by teaching bystander scenarios and intervention techniques (Landry & Blackburn, 2024). Preliminary research on this program suggests that students who participate in Waves of Change show increased knowledge about campus sexual violence and bystander intervention skills relative to students who do not participate in the program (Lambe et al., 2025).

Preventing sexual violence is crucial for the health and well-being of all, particularly in high-risk settings such as post-secondary campuses and workplaces. Universal preventions like Bringing in the Bystander have shown significant promise in addressing the pervasive issue of sexual violence that affects countless Canadians each year. In response to the call for more effective sexual violence prevention strategies, new programs such as Atlantic Canada’s Waves of Change, continue to emerge. Preliminary evaluations of the program’s effectiveness are to be conducted in 2024–2025 through St. Francis Xavier University, marking an important step in advancing evidence-based sexual violence prevention efforts in Canada.

The Importance of Evidence-Based Prevention and Program Evaluation

In discussing prevention programs, it is essential to emphasize the importance of evidence-based approaches to prevention, including rigorous evaluations of program efficacy and effectiveness in achieving intended outcomes (Stangor & Walinga, 2014). Programs are only worth implementing broadly once there is substantial evidence demonstrating their ability to prevent or delay the onset of the targeted concern or disorder. Otherwise, program effectiveness may be mistakenly assumed based on anecdotal evidence (Nation et al., 2003), which poses significant risks. Without proper evaluation, we may be investing in and delivering programs that at best do nothing, and at worst may actually be making things worse! When prevention programs exacerbate the issues that they aim to address, this is known as an iatrogenic effect (American Psychological Association, 2021, May; Bootzin & Bailey, 2005; Werch & Owen, 2002; West & O’Neal, 2004).

There are multiple examples in psychology’s history of well-intentioned prevention programs that either failed to produce positive changes or even had unintended, harmful consequences. For instance, a cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) group-based prevention program targeting at-risk youth inadvertently increased smoking rates and teacher-reported delinquency (Poulin et al., 2001). Similarly, a targeted CBT group program for adolescents with conduct disorders found that grouping students with delinquency problems together could reinforce and amplify their problematic behaviours (Bootzin & Bailey, 2005). These findings highlight the risks associated with certain group-based interventions, particularly those that cluster individuals with similar behavioural challenges. By documenting and analyzing these iatrogenic effects, researchers and clinicians have been able to refine intervention strategies and develop more effective, evidence-based approaches. This growing body of research has contributed to a broader understanding that group-based interventions for deviant behaviours can do more harm than good, reinforcing the need for individualized, context-sensitive prevention and treatment programs.

Perhaps the most notable example of a prevention program that lacked evidence is Project D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Education). Introduced across the United States in the 1980s, this universal school-based substance use and crime prevention program reached millions of students a year (Kochis, 1995; Rosenbaum & Hanson, 1998). The program involved local police and school-educators delivering sessions focused on resisting drug use and peer pressure and understanding the consequences and harms of drug use (Rosenbaum & Hanson, 1998). However, this program was not formed like many other programs in this chapter with psychologists and theory, it was developed by the Los Angeles (L.A.) Police Chief, with some collaboration with L.A. schoolboards and designed to be led by police officers (Cohen et al., 2005). Even a decade after its inception, researchers were questioning the program’s lack of empirical support (Kochis, 1995). Subsequent studies showed the ineffectiveness of Project D.A.R.E., with research spanning five years showing no significant effect for reducing students’ drug use at both one- and five-year follow-ups (Clayton et al., 1996). Ten-year evaluations echoed these findings (Lynam et al., 1999), and meta-analyses consistently reported no measurable benefits beyond what could occur by chance, with the exception of a significant reduction in tobacco use (Ennett et al., 1994; West & O’Neal, 2004). Alarmingly, Project D.A.R.E. was found to have iatrogenic effects in some cases, such as producing a small but significant increase in drug use among suburban adolescents (Rosenbaum & Hanson, 1998; Werch & Owen, 2002). Remember that even small effects can have disastrous outcomes when applied to a large population, such as the millions of students who received Project D.A.R.E. programming.

Now you may be wondering how we prevent such things from happening again? How can we ensure that programs are effective and evidence-based? While a complete exploration of best practices in evidence-based prevention is beyond the scope of this chapter, two of the many different factors to consider are highlighted below. First, even before implementation, it is important that prevention initiatives are grounded in evidence-based theories that establish specific and testable outcomes. These outcomes allow the opportunity for rigorous scientific evaluation and avoids reliance on weak or poorly formed hypotheses (Bootzin & Bailey, 2005). Second, when evaluating a program’s effectiveness, it is important to consider if the studies conducted used widely accepted and validated study designs, such as randomized-controlled trials, to compare outcomes between groups who received an intervention and those who did not (Chiang et al., 2015; Comer et al., 2013). Of course, other important best-practices within psychological research include ensuring adequate sample sizes for sufficient statistical power and replication of results across diverse populations. Ultimately, the importance of having solid evidence in psychology cannot be overstated; it is absolutely paramount that our prevention techniques be backed by rich empirical evidence. Psychologists risk both not making a difference and even causing harm if they fail to prioritize these practices and think critically about prevention approaches and the evidence for or against them (or the lack of evidence altogether). Broadly launching untested programs jeopardizes public trust and the wellbeing of potentially huge numbers of people, underscoring the need to avoid engaging in prevention lacking evidence of effectiveness.

Conclusion

The development of prevention programming in clinical psychology reflects a shift from its traditional focus on individual treatment to addressing mental health challenges and societal needs on broader scales. Rooted in the contributions of community psychology, prevention has evolved to include universal approaches aimed at whole populations, targeted approaches for at-risk groups, and indicated approaches for individuals showing early signs of mental health concerns. These approaches aim to reduce risks, delay the onset, and mitigate the severity of mental health disorders. Distinguishing prevention from intervention underscores their complementary roles, with prevention focused on reducing risk in those not yet diagnosed and intervention addressing existing disorders.

Evidence-based prevention lies at the heart of effective programming, ensuring initiatives are grounded in empirical research, utilize validated methodologies, and are rigorously evaluated for their efficacy. This focus enhances program effectiveness for achieving intended impact while safeguarding against unintended harm, as illustrated by the shortcomings of historical initiatives like Project D.A.R.E. In Canada, prevention programming addresses diverse challenges, including preventing suicide, substance misuse, bullying, and sexual violence. Programs like PreVenture, The Body Project, and WITS exemplify culturally responsive, evidence-based prevention approaches tailored to the unique needs of Canadian populations. These initiatives show the value of integrating empirically based best practices with locally relevant solutions to effectively mitigate risks and delay the onset of mental health disorders. By understanding the history, principles, and applications of prevention in clinical psychology, including its distinctive development in the Canadian context, we can appreciate its role in building healthier communities and addressing mental health challenges for across the lifespan.

Chapter exercises

Resources

Suicide prevention resources

- https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/suicide-prevention/

- 9-8-8 Suicide crisis helpline (available anywhere in Canada)

- https://novascotia.cmha.ca/cast-program/ (CAST program Nova Scotia)

Substance Use

- https://www.camh.ca/

- https://mha.nshealth.ca/en/services (Nova Scotia mental health and addiction resources)

Eating disorders

- https://nedic.ca/

- 1-866-633-4220 (416-340-4156 in the GTA) (NEDIC hotline)

- https://eatingdisordersns.ca/ (Nova Scotia-specific support)

Bullying

- https://www.bullyingcanada.ca/

- https://www.prevnet.ca/bullying-policy-legislation/nova-scotia/ (Nova Scotia-specific information)

Sexual Violence

- https://endingviolencecanada.org/sexual-assault-centres-crisis-lines-and-support-services/

- https://www.salalsvsc.ca/get-support/

- 1-877-392-7583 (Salal sexual assult hotline)

- https://breakthesilencens.ca/find-help/where-to-get-help/ (Nova Scotia support)

Media Attributions

- Public health prevention © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Scope of prevention spectrum © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Children Playing in Playground © Jlbirman1 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- CAST

- nedic-logo_full

- personholdingbottle

- PinkShirtDay © New Brunswick is licensed under a Public Domain license

- WITS © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- WOC

- Logo of Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) © Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) is licensed under a Public Domain license

In the context of clinical psychology, prevention teaches individuals at risk for developing mental health or substance use disorders the skills and strategies they need to reduce their risk of developing the disorder, delay the onset of the disorder, or reduce the disorder’s severity.

A broad approach that targets an entire population to prevent or delay the onset of mental health issues by addressing key factors, such as increasing awareness and reducing harmful social norms.

A targeted prevention approach aimed at helping individuals with specific risk factors for developing a mental health disorder. It focuses on teaching skills to reduce risk factors and prevent the onset of the disorder.

A prevention approach for individuals already showing early signs and symptoms of a disorder, but do not meet clinical diagnostic criteria. It involves more specific clinical interventions tailored to the disorder to prevent symptoms from worsening.

A clinical approach that provides treatment to individuals with mental health conditions at an early stage. The goal is to reduce the negative effects of the condition while reducing the need for future professional support.

The scientific and objective evaluation of a program’s efficacy, effectiveness, quality, and overall value to determine whether it works as intended and achieves its desired outcomes.

The extent to which a program or treatment results in the expected outcomes under ideal, controlled research settings.

A statistical measure of the magnitude (size) of difference between groups, such as the impact of an intervention compared to a control condition.

High-quality research design used to evaluate interventions. Participants are randomly assigned to either an intervention group, receiving treatment, or a control group, which receives no treatment. Comparing outcomes between groups determines the intervention’s efficacy and effectiveness.

The extent to which a treatment or program produces beneficial results in real-world settings, such as routine clinical practice, without the controlled conditions of research settings.

The number of individuals who must receive a treatment or prevention program for one person to avoid a negative outcome, such as developing a mental health disorder, that would have likely occurred without such treatment.

An unintended harmful effect of a treatment or intervention, where instead of improving outcomes, it leads to negative consequences (e.g., increasing the rates of the mental health disorder the prevention program intended to reduce).