10 Third-Wave Cognitive Behavioural Approaches: DBT and ACT

Jessie N. Doyle

Imagine you are a psychologist working in an inpatient psychiatric clinic. You notice that a subset of your clients are hospitalized for persistent self-harming behaviours, and you quickly realize that your CBT training is not helping them. If anything, your efforts to help these patients identify and correct errors in thinking seem to be responded to with anger and other intense emotions. One client, Jane, exemplifies this group of patients. A 21-year-old woman, Jane has a history of being victimized, including childhood sexual and psychological abuse by her stepfather between the ages of 11 and 16. During her adolescence and early adulthood, Jane engaged in many sexually risky behaviours and drank heavily. Although she has attempted to reduce the frequency of her drinking, she often drinks as a method of coping with distressing emotions and Jane tends to drink so much on a given occasion that she ‘blacks out.’ Jane’s relationships – especially her intimate/romantic ones – are quite tumultuous. In each relationship, she finds herself doubting that her partner actually cares for her. She quickly interprets any instance of her partner’s unavailability as examples that they are going to leave her, all because they (from her perspective) view her as “not good enough.” When Jane detects these sorts of signs, she experiences waves of anger, fear, and emptiness, and will do almost anything to feel better in the moment, such as drinking, binge eating, speeding and/or drinking while driving, hooking up with a former romantic partner, and severe self-injurious behaviour. When working with Jane, you notice that she interprets even gentle attempts to challenge cognitive distortions as though you believe that there something is “wrong” with her. She has prematurely left many sessions in tears and in general has significant difficulties with regulating her emotions, especially when feeling misunderstood, dismissed, or abandoned. You begin consulting with colleagues about appropriate and evidence-based interventions to support Jane and they suggest that you look into Dialectical Behaviour Therapy.

- Describe the underlying theory, processes and mechanisms of change, and core components of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).

- Identify clinical presenting concerns for which DBT and ACT are indicated.

- Recount the strength of the current evidence base in support of DBT and ACT.

- Identify the adequacy of the available evidence for treating 2SLGBTQIA+ and racialized clients with these modalities.

- Describe research that has been conducted on an Atlantic Canadian DBT-based program.

Making (Third) Waves: Rocking the Boat with Acceptance and Dialectics

As you have read in previous chapters, the contours of psychotherapy have changed – sometimes drastically – in accordance with the psychological and cultural zeitgeist. In the late 1800s, when psychotherapy first came on the scene, it was formulated and promoted as “the talking cure” (Freud & Breuer, 1895/2004). Freud’s ‘talking cure’, also known as psychoanalysis (and later iterations known as psychodynamic psychotherapy) was and is interested in producing deep and meaningful change in a client’s personality structure by identifying and interpreting unconscious conflicts (Shedler, 2006). Interest in both the unconscious and conscious mind, however, waned into the mid-20th century (Shedler, 2006). A penchant for systemization and scientific evidence supplanted prevailing clinical traditions that, at the time, did not have sufficient empirical support or clearly defined interventions and were conceptually convoluted (Puligandla, 1976). Behaviourists such as Skinner and Watson were breaking ground into the nature of human learning. Along with these conceptual changes to the theoretical landscape, the so-called ‘first wave’ of behaviour therapy emerged.

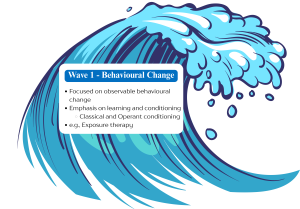

Behaviour therapy has been categorized into three ‘waves’, a phrase retroactively coined by American psychologist Steven Hayes (2004). In Hayes’ (2004) estimation, which has become well-accepted within the psychological community, behaviour therapy has undergone three major shifts. These shifts have, in turn, guided research, theory, and practice. The first wave is in reference to practices that focus purely and exclusively on behavioural change, and are based largely on conditioning (learning) principles (Hayes, 2004). Rather than address internal and psychological conflicts, the goal of first wave behaviour therapy was strictly to change clients’ behaviour. Although there is much utility in strategies that produce behavioural change, an emerging concern with the first wave was that it had stripped psychotherapy of its ‘psycho’ root (recall that the prefix ‘psycho-‘ is derived from the Greek word psȳchḗ which loosely translates to spirit, soul, or mind). That is, to some, the first wave behavioural movement had resulted in a dismissal of fundamentally human issues and capacities (Hayes, 2004).

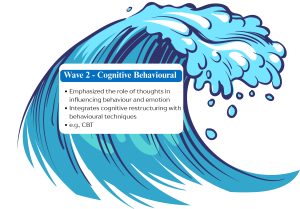

A second shift in the psychological zeitgeist ushered in the second wave of behaviour therapy. This shift was toward information-processing models and internal psychological machinery (which, perhaps uncoincidentally co-occurred with the inception of computers and software; Mandler, 2002; Miller, 2003). This second shift also reintroduced the world of psychology to the notion that the mind seems to play an important role in the experience and production of distress and maladaptation. This second wave can be traced to the late 1960s, as the new cognitive psychology movement was emerging. B. F. Skinner was conceding the reality of internal events (thoughts, emotions, etc.) and the validity of studying these phenomena scientifically, but still asserting that doing so was unnecessary to understand overt behaviour (Skinner, 1957). Cognitive therapy (e.g., Beck et al., 1979) delineated cognitive explanations of behaviour change, and focused on changing irrational or distorted thinking styles and pathological schemas through challenging their validity. Aaron Beck, the father of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as we now know it, initially intended to provide an alternative to both psychoanalysis and behaviour therapy (Beck, 1979). Instead, the cognitive-based second wave largely absorbed the behaviour-based first wave. Cognitive concepts were given primacy and behaviour principles given much less focus in theory and practice.

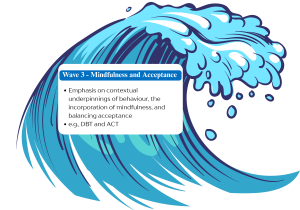

CBT – in its second wave iteration – has tended to be rather mechanistic, having been borne out in part by a cognitive movement that appealed to computers as a metaphor for the mind (Miller, 2003). Moreover, despite its widespread popularity and use, there were clear indicators that CBT and its variants (behaviour therapy, cognitive therapy) do not work for everyone. Studies and reviews published in the late 1980s and early 1990s (e.g., Keller & Boland, 1998; Linehan, 1993; Safran et al., 1988; Shea et al., 1992; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993) showed that these models were producing suboptimal long-term results for some clients, not protecting against treatment dropout, and at best ineffective at treating treatment-resistant, complex, and co-occurring disorders. In consequence, a third wave began to emerge – one characterized by an emphasis on contextual underpinnings of behaviour, the incorporation of mindfulness, and balancing acceptance and change strategies to engender therapeutic progress (Hayes, 2004; Linehan, 1993; Ruork et al., 2022). Although several novel therapeutic modalities were ushered in with the third wave in the late 1990s, two modalities continue to ‘make waves’ for their evidence base and widespread use: Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 2012).

DBT and ACT extend earlier iterations of CBT by adopting a contextualist, principle-focused approach, meaning they are more sensitive to the role of context in understanding clinical concerns and are tailored to the needs and unique characteristics of a given client (Ong et al., 2020). Concrete examples of this follow in the chapter. These therapies also incorporate previously underemphasized facets such as values, acceptance, and dialectics (Hayes, 2004). Despite notable differences between DBT and ACT, they both adhere to a behaviouralist foundation, and emphasize the role of mindfulness, emotions, emotion regulation, acceptance (Ruork et al., 2022). Both therapies represent paradigmatic shifts in how we understand and treat psychological disorders, including historically difficult-to-treat (i.e., treatment resistant or ‘refractory’) disorders. Thus, DBT and ACT are considered “third-wave” therapies.

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT)

American psychologist Marsha Linehan began developing DBT in the 1970s after observing that there were few effective psychological treatments available to treat chronically suicidal or self-injurious patients (Linehan, 1993). When applying for research grants to further her work, she learned that attaching a specific diagnosis to her research proposal was necessary. Reasoning that her patient population, and their suicidal and otherwise harmful behaviour most closely resembled the diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD), she began to conceptualize DBT as a treatment for BPD.

Linehan was trained in the tradition of behaviour therapy but found that these difficult-to-treat patients experienced any attempts to change their behaviour as fundamentally invalidating. Simultaneously, these same patients viewed a practitioner’s acquiescence or total acceptance of them as a dismissal of the deep psychological suffering they experienced. As a consequence, and informed by her training in Zen Buddhism, Linehan formulated a psychotherapy predicated on dialectics – a synthesis between thesis and antithesis. DBT practitioners will tell you that the entirety of this psychotherapy hinges on many opposing things being true at once. For example, a DBT therapist might validate a client’s intense emotional pain by acknowledging its legitimacy and origins in past trauma while simultaneously encouraging the client to adopt new coping strategies to reduce self-harming behaviours. Indeed, the pinnacle dialectic is the tension between the thesis of behaviour therapy (i.e., the client needs to change their behaviours) and the antithesis of acceptance (the therapist needs to be totally accepting of who the client is). As such, therapists are both oriented to change and simultaneously oriented to acceptance. The therapeutic whole of DBT is consequently comprised of three foundations: behaviourism, acceptance, and dialectics.

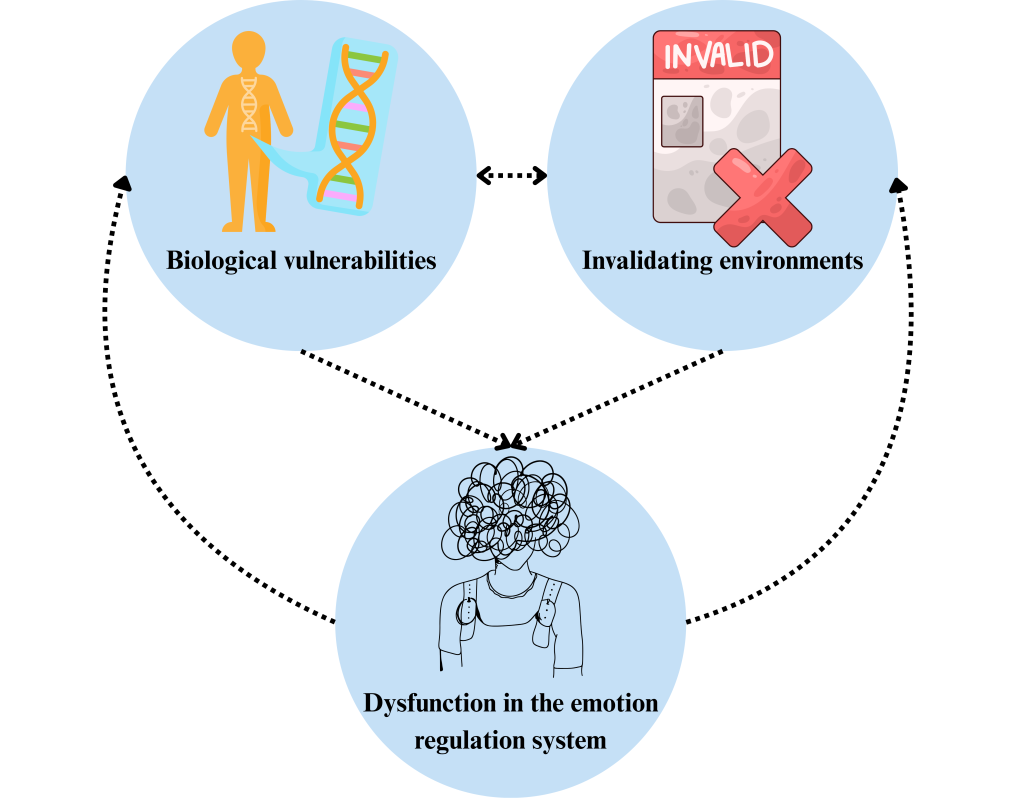

Concurrently, Linehan developed a theoretical model to explain how the behaviours that DBT aims to treat develop and are maintained – the biosocial theory of personality functioning (Linehan, 1993). The basic premises of Linehan’s biosocial theory are that 1) BPD is underpinned by dysfunction in the emotion regulation system, and 2) this dysfunction arises because of the interaction between biological vulnerabilities (e.g., temperament) and an early invalidating environment.

DBT’s Biosocial Theory

Biosocial theory suggests that individuals who develop BPD are biologically susceptible to emotional sensitivity. Their emotional sensitivity makes them more vulnerable to social invalidation. In addition to a biological predisposition to emotional sensitivity, biosocial theory assumes a poorness of fit between the individual and their environment. This mismatch between the individual’s predisposition and their environment results in chronic invalidation of the individual. Invalidation, in which the inner experience of an individual is dismissed, punished, and reinforced as ‘wrong’, contributes further to the development of BPD. In this way, biosocial theory is transactional; it asserts that reciprocal interactions between biological vulnerabilities and invalidating environment(s) increase the likelihood of invalidated emotions, which increase emotional vulnerability. This cycle, from a biosocial theory perspective, results in a history of invalidation, impaired long-term functioning, and chronic emotion dysregulation. To summarize, people who end up developing and being diagnosed with BPD have a biological vulnerability to difficulty with regulating emotions, and this is compounded by repeated invalidation particularly throughout formative developmental years.

Emotion dysregulation is viewed as a combination of high emotional vulnerability and an inability to regulate emotions. As such, individuals with BPD are highly sensitive to emotional stimuli, they experience emotions intensely, and return to emotional baselines slowly, while simultaneously harboring a lack of healthy emotion regulation skills. From a biosocial theory perspective, all other BPD characteristics (interpersonal, behavioural, cognitive, and self-dysregulation) are secondary to and emanate from this fundamental and chronic dysfunction in the emotion regulation system.

By first understanding biosocial theory, we can then understand the DBT therapeutic model. As an example, for a client whose emotions and emotional expressions were persistently mocked and belittled by their primary caregiver, the DBT therapist will help the client identify the function and origin of their emotions, validate the client’s emotional experience, and help them develop self-validation strategies. This therapeutic response is all in the services of short-circuiting the client’s pattern of experience invalidation, dysregulated emotion, and subsequent ineffective behaviour. Generally, biosocial theory and the DBT model presupposes that, because of the ongoing interaction between a person’s biology and predisposition, with an invalidating environment, that individual did not have the chance to learn how to regulate and effectively communicate their naturally intense emotions. Consequently, these individuals engage in maladaptive behaviours (e.g., self-harm) that make managing their emotional life even worse, and are not effective in producing the sort of life that the person wants. These maladaptive behaviours, from a DBT lens, are viewed as skill deficits. Gaining skills to better regulate emotions is a key therapeutic target.

In the years since the biosocial theory of emotion dysregulation was proposed, there has been considerable empirical investigation into both the biological (see Niedtfeld & Bohus, 2019 for a review) and social (see Grove & Crowell, 2019 for a review) bases. However, evaluation of biosocial theory as a whole is limited but promising (Arens et al., 2011), with one longitudinal study examining the transactional relationship between individual vulnerabilities and parental invalidation providing partial support for the biosocial theory of BPD (Lee et al., 2023). While biosocial theory and the origins of DBT are focused on BPD, this therapy has since been applied to other disorders that we will cover later in this chapter.

Watch an introduction to DBT

Video by Psych2go, “What Is Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT),” published on YouTube, 2024.

Treatment Approach: DBT’s Core Components

The treatment structure of standard DBT, as originally formulated by Linehan, involves 1 hour of individual therapy and 1.5 to 2 hours of group therapy per week. These sessions are typically delivered for a duration of 1 year. Another key component is skills coaching via telephone, which is intended to be available for 24 hours a day. Finally, DBT clinicians attend a weekly DBT consultation team meeting, where they can discuss their caseload and encourage each other to apply DBT skills to themselves when facing tricky clinical moments. It should be noted here that, according to Linehan, therapists can only truly consider themselves to be delivering DBT in its intended form if the therapy structure is as described above.

DBT has four stages of treatment, with Stage 1 being the longest. Stage 1 is based on a hierarchy, whereby the first things addressed are life-threatening behaviours (e.g., suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury), then therapy-interfering behaviours (e.g., missing appointments, not completing homework), then behaviours that negatively impact the client’s quality of life (e.g., risky sexual behaviour, excessive relationship conflict; Koerner, 2011; Linehan, 1993). Stage 1 can take upwards of a year for clients with especially severe presentations (Linehan, 1993). At Stage 2, which begins only when the client has reasonable mastery over Stage 1 targets (Linehan, 1993), treatment addresses stress that has resulted from historical trauma, and any present co-occurring disorders. During Stage 3, treatment aims to enhance the client’s self-respect and ability to manage the ordinary ups-and-downs of life. Finally, Stage 4 integrates skills learned in the first three stages and helps the client further their self-reliance and self-validation independent of the therapist (Swenson, 2016).

Throughout treatment, DBT utilities several key techniques. The first is skills training, which follows from DBT’s assumption that clients want to improve but they lack the skills do so (Linehan, 1993). DBT skills training has four modules. The first module is Mindfulness, where clients learn mindfulness ‘how’ skills (i.e., the way you practice – nonjudgmentally, objectively, and one-mindfully) and mindfulness ‘what’ skills (i.e., what you do – observe, describe, and participate). These skills are derived from Zen Buddhism and are meant to promote ‘wise mind’ – the synthesis between ‘emotional mind’ (i.e., operating on urges) and ‘reasonable mind’ (i.e., operating solely on logic). Wise mind allows for the integration of emotion and reason and is thought to facilitate more balanced decision-making and behaviours (Linehan, 1993).

The second DBT skills training module is Distress Tolerance, which includes skills intended to help clients to accept present emotional suffering and avoid doings that could worsen or prolong their pain (Linehan, 2015). Distress Tolerance skills help clients get through high-stress moments and are best implemented when a person’s emotions are so intense that they are having a hard time accessing more sophisticated skills that would require planning ahead. Examples include the TIPP skills, which work by changing your body chemistry through Temperature, Intense exercise, Paced breathing, or Progressive muscle relaxation, and radical acceptance to the present moment/situation.

The third DBT skills training module is Emotion Regulation, involving skills that aid clients in identifying, understanding, and regulating their emotions. The ultimate goal of this module is to help clients reduce their susceptibility to mood swings and more effectively manage the day-to-day. During this module, clients are taught skills like problem-solving, being effective (i.e., focusing on clear goals), and opposite-to-emotion action (i.e., doing the polar opposite of what your emotion urge tells you to do).

The final DBT skills training module is Interpersonal Effectiveness. These skills are designed to help clients be more effective and balanced in how they approach their relationships (intimate and otherwise). Clients learn how to respect the needs and wishes of others AND themselves. For instance, DEAR MAN is a skill that helps clients communicate effectively by Describing the situation objectively, Expressing their feelings about the situation clearly, Asserting what their needs are, Reinforcing when responding to positively, (staying) Mindful of communication goals, Appearing confident, and (being open to) Negotiate.

Test yourself!

Mechanisms of Change in DBT

The core mechanism of change in DBT – that is, the mechanism through which therapeutic change is thought to occur – is emotion regulation (Chapman & Owens, 2020). Indeed, DBT is likely as effective as it is because of its ability to improve clients’ emotion regulation capacities (see Boritz et al., 2019 for a review). DBT skills training is designed to directly target emotion regulation deficits, and more use of DBT skills is associated with reductions in BPD symptom severity (Stepp et al., 2008), symptoms of depression, suicide attempts, and non-suicidal self-injury (Barnicot et al., 2016; Neacsiu et al., 2010). DBT skills training, as a standalone treatment, also accounts for improvements in emotion regulation, anxiety, and depression (Neacsiu et al., 2014). An analysis of the comprehensive standard DBT protocol demonstrated that the DBT skills training produced the largest improvements in depressive and anxiety symptoms and reductions in non-suicidal self-injury compared to other treatment components (Linehan et al., 2015). Completion of skills training homework has also been found to enhance therapeutic change and outcomes in target behaviours in a sample of outpatients completing an intensive DBT program (Edwards et al., 2021). In summary, the existing literature suggests that improved emotion regulation skills, acquired primarily via skills training, is among the foremost mechanisms of change in DBT (Ruork et al., 2022).

Another central mechanism of change is DBT mindfulness skills, which have been associated with reduced emotional instability and interpersonal problems compared to other DBT skills (Miller et al., 2000). DBT mindfulness skills have also produced improvements in depression (Soler et al., 2012), general psychopathology, emotional reactivity (Feliu-Soler et al., 2014), and BPD symptoms (Perroud et al., 2012). Therapist validation is also presumed to be an important therapeutic mechanism of change.

Review

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

ACT’s founder Steven Hayes was significantly influenced by work he did early in his career on Beck’s cognitive therapy. Hayes focused on the treatment component of ‘distancing’, in which thoughts are held as hypotheses rather than taken as fact. Hayes’ (1987) functional analysis on cognitive distancing in cognitive therapy demonstrated that thoughts themselves cannot directly cause ineffective behaviour. Hayes’ early work suggested that we need to understand and change the context of thoughts and feelings in order to change the impact that they have on us. Hayes was also influenced by his own experience with panic attacks. He made many efforts at reducing his anxiety, which required him to constantly evaluate anxiety levels and resulted in anxiety playing the leading role in his life. After several years, he began to experiment with adopting an acceptance orientation to his anxiety and focusing instead on engaging in values-based actions. Eventually, Hayes found that a life that had been consumed and made small by anxiety, began to expand, and his panic attacks ended.

Although ACT is informed by Hayes’ personal experience, make no mistake – it too has rich philosophical and theoretical underpinnings. To be precise, ACT is based on a branch of philosophy known as functional contextualism (Hayes et al., 1988; Hayes et al., 1993), which involves (a) focusing on the whole event, (b) being sensitive to the role of context in understanding the function of an event, (c) viewing ‘truth’ as what is most pragmatic/useful, and (d) identifying specific scientific goals. What’s important to know here is that ACT and relational frame therapy (RFT) – the theory from which ACT is derived – are not concerned with finding out what is objectively true. Rather, ACT is an intervention intended to evoke an ongoing focus on living a meaningful life according to one’s values.

ACT’s Relational Frame Theory (RFT)

ACT is based on Relational Frame Theory (RFT), which asserts that the crux of human language and thought is relational learning, meaning that we can link events together even without these events being related in a formal and obvious way (Hayes, 2004). If that sounds abstract, it’s because it is. At the most basic level, RFT highlights how incredible humans are at drawing associations between events and the role that language plays in our tendency to make associations that might otherwise seem a bit arbitrary. RFT claims that human language and thought depend on deriving “relations among events-among words and events, words and words, events and events” (Hayes, 2015, p. 875). Put differently, RFT is a contextualistic theory of cognition. The main takeaway from this theory is that RFT argues that human suffering and psychopathology are both precipitated and maintained by rigid stimulus relations (cognitive fusion), and efforts to avoid thoughts that arise from stimulus relations (experiential avoidance) (Hayes, 2004; Ruork et al., 2022).

According to RFT, networks of relations (amongst events, words, etc.) are really hard and perhaps impossible to extinguish altogether (Hayes, 2004). Because of the power of these relational networks, it is suggested that individuals become disconnected from the present moment experience. Instead, we become more caught up in cognition, in evaluations, in verbal rules, and become fused with cognition – this is referred to cognitive fusion. RFT posits that experiential avoidance – the myriad of ways in which we attempt to suppress or avoid our thoughts and feelings – are inbuilt processes of human language (Hayes, 2004). Unlike other animals, we simply cannot get away from painful experiences just by changing the situation. In consequence, we try to control our pain by avoiding painful thoughts and feelings, which only serves to cue the very things we are avoiding [whatever you do, don’t think of a pink elephant!!…see what I mean?]. RFT suggests that reducing suffering requires changing the context in which the thoughts occur (versus changing the form or frequency of the thoughts themselves, as one typically does in cognitive therapy).

As a basic theory of human language and cognition, RFT has received a respectable amount of empirical support (see O’Connor et al., 2017 for a summary). Research specifically evaluating the particular linkages between RFT and ACT is relatively new, but promising (e.g., Gil-Luciano et al., 2017). Unlike DBT practitioners, ACT clinicians do not typically dive into the nuances of RFT with their clients, but there is no available research to suggest that this lack of theoretical integration into practice influences ACT’s effectiveness.

Test yourself!

Treatment Approach: ACT’s Core Components

Whereas DBT epitomizes a structured intervention model, for ACT, the treatment approach mirrors its aims of cultivating flexibility. That is, ACT does not dictate or delineate a specified treatment structure, method of delivery, or even number of sessions to accomplish intended outcomes. ACT is frequently delivered both as individual therapy (Bluett et al., 2014) and/or group therapy (Coto-Lesmes et al., 2020). Regardless of the method of delivery or length of treatment, there are six core processes encompasses by ACT that may be addressed throughout therapy.

These six core processes include: (1) acceptance, which is the intentional awareness of and openness to current experiences (including thoughts and emotions) without attempts to change them; (2) cognitive defusion, which is the process of creating distance from (“de-fusing”) and reducing attachment to thoughts; (3) contact with the present moment, by engaging with all current experiences without judgment; (4) self-as-context, which refers to enhancing metacognition and realizing that the ‘self’ is not simply the content of what we experience; (5) identification of core values, which are our guiding principles and inform how we behave and engage with the world; (6) and committed action, which basically means living in line with those identified core values (Hayes et al., 2012).

Learn more!

Unlike DBT, ACT does not identify treatment targets in an a priori hierarchical fashion. Instead, presenting concerns are conceptualized on a case-by-case basis and treatment targets may then be prioritized based on any given case conceptualization. During case conceptualization and throughout treatment, clinicians will identify in what areas client behaviours are deficient across the six core processes, and in what ways these deficits keep clients ‘stuck’ in unworkable and ineffective ways of navigating the world (Hayes et al., 2012). For example, a client with depressive symptoms may be stuck in a pattern of withdrawal and avoidance, especially of situations that evoke feelings of low self-esteem, which could be improved by recognizing that he is not his thoughts (self-as-context process), clarifying his core values (values process), accepting thoughts non-judgmentally (acceptance process), and engaging in values-based and healthy activities (committed action process). In consequence, the clinician has quite a bit of autonomy to determine (in collaboration with and with the consent of the client) areas of intervention and when and how to intervene.

The six core processes are theorized to be highly interdependent , meaning that intervening at the level of cognitive defusion, for instance, is presumed to also influence acceptance, committed action, and so on. One of the benefits of ACT is that, for each of the six core processes, there are a slew of different techniques that clinicians can draw on. Should a client be struggling with chronic pain, for instance, an acceptance strategy such as intentional and mindful attention to physical sensations, thoughts, feelings, and urges may be useful. If a client has a belief of “I’m unlovable” that is causing distress, they may practice a defusion technique such as repeating the thought incessantly until the words start to lose their meaning (try it…next time you notice a distressing thought…repeat the thought to yourself dozens of times until the words become devoid of their potency). Gaining contact with the present moment can be accomplished through the “dropping the anchor” exercise, which orients clients to the present and facilitates choice in responding to a given situation. In order to address distressing core beliefs and overidentification with labels, self-as-context techniques are utilized to help clients disentangle from the conceptualized self, become aware of ongoing experiences, and shifts in perspectives (Hayes et al., 2012). These techniques, such as the Observer Perspective exercise wherein one attends to the different roles and settings one has occupied across time, are intended to promote a stable sense of self across time and the self as that which holds (rather than is) the experiences. Identification of core values occurs via several exercises, such as the Values Bullseye, that directly inquire about what is personally and inherently important to the individual and then questioning the degree to which current modes of living are aligned with the identified values. Committed action is invoked following values identification by elucidating effective values-based action goals and other techniques such as monitoring values-based actions and what these behaviours produce.

Hopefully, by providing examples of the six core process techniques, it is clear how closely related are each process, and why there is no predetermined sequence for targeting behaviours in therapy. Thus, an ACT clinician should strive to embody psychological flexibility themselves, as they are typically not following a structured manual and work with whatever the client brings up in a given session. Not every client will require in-depth intervention in all domains. Case conceptualization is necessary in guiding decisions of what process to address and which techniques to use to accomplish therapeutic goals. Session-by-session, the therapist and client may address one, or multiple processes all in the service of enhancing psychological flexibility. Nevertheless, at least one core process should be actively targeted within session in order to maintain fidelity to ACT.

ACT key takaways

| ACT Core Process | Definition | Example Technique | Clinical Applications |

| Acceptance | Willingness to experience thoughts, feelings, and sensations without judgment or avoidance. | Mindfully attending to physical sensations, thoughts, and urges in the context of pain. | Chronic pain, distressing emotions, and resisting uncomfortable experiences. |

| Cognitive Defusion | Learning to step back from thoughts and see them as words/images rather than literal truths. | Repeating the thought “I’m unlovable” until the words lose meaning and distress decreases. | Self-critical or distressing thoughts, unhelpful beliefs. |

| Contact with the Present Moment | Fully engaging in the here-and-now with openness and awareness. | “Dropping the anchor” exercise to orient to the present and create choice in responding. | Rumination, anxiety, and avoidance of current experiences. |

| Self-as-Context | Seeing the self as the perspective from which experiences are observed, not the content of those experiences. | Observer Perspective exercise—reflecting on roles/settings across time to promote a stable sense of self. | Overidentification with labels, rigid self-concepts, and distressing core beliefs. |

| Values | Clarifying what is personally meaningful and important to guide action. | Values Bullseye exercise—identifying core values and assessing alignment with life. | Lack of direction, low motivation, feeling disconnected from meaning. |

| Committed | Taking effective, values-based steps toward goals despite obstacles. | Setting values-based action goals, monitoring behaviours, and assessing outcomes. | Avoidance patterns, disengagement from life, difficulty making lasting change. |

Mechanisms of Change in ACT

The overarching aim of ACT is to improve psychological flexibility, which is broadly conceptualized as being in touch with the here-and-now and engaging in values-based behaviour. Experiential avoidance, although previously viewed as the primary aim of treatment, is now viewed as an unhelpful contributor to a lack of psychological flexibility (Wilson et al., 2011; Hayes, 2004). Currently, there is fairly robust evidence that psychological flexibility is an important mechanism of therapeutic change in ACT. For example, psychological flexibility mediates (explains) the relations between ACT treatment and social anxiety, depression (Forman et al., 2007; Niles et al., 2014), distress (Rost et al., 2012), and improved functioning and quality of life (Forman et al., 2007). A recent meta-analysis (i.e., an analysis of multiple studies) indicated that psychological flexibility plays a substantial role in improvements in depressive symptoms in adolescents (Lopez-Pinar et al., 2025).

In pursuit of the broader aim of psychological flexibility, ACT`s six core processes are the targets for treatment that are themselves theorized to be core processes of change. Although these six core processes are the crux of ACT, including session-to-session interventions, they have received relatively less research attention than psychological flexibility (Stockton et al., 2019). Nevertheless, values identification and committed action are shown to explain the relationship between ACT and quality of life improvements in individuals with epilepsy (Lundgren et al., 2008). Committed action is also associated with reduced depressive symptoms (Forman et al., 2007) and tinnitus distress (Hesser et al., 2015); however, this relationship was not unique to ACT.

Test yourself!

Effectiveness of Third-Wave Therapies

As highlighted in previous sections, ACT is inherently flexible, which has made it more challenging to study in a rigorous fashion (via randomized controlled trial, etc.) as compared to DBT’s highly structured nature, which has been especially conducive to tightly controlled efficacy studies. Since their respective inception, both DBT and ACT have garnered notable empirical support, especially for specific psychological conditions and issues. Broadly speaking, DBT is a gold standard treatment for BPD (American Psychological Association; APA, Div 12, n.d.) but has begun to amass evidence in support of its efficacy in treating other disorders, like substance use disorders and mood disorders. By contrast, ACT is a gold standard treatment for chronic health conditions (APA, Div 12, n.d.), but it too has begun to gain research support in treatment various forms of psychological disorders. The following subsections provide a brief overview of the current state of efficacy and effectiveness research for both DBT and ACT. Please keep in mind that despite promising results for both DBT and ACT in treating a variety of psychological disorders, in keeping with Division 12 (Society for Clinical Psychology) of the APA, we are still awaiting a robust pool of high-quality evidence that these treatments improve symptoms and functional outcomes for most of the following disorders. The table at the end of this section summarizes the strength of research support for DBT, ACT, and CBT in treating these psychological disorders.

Mood Disorders

In a meta-analysis, DBT was identified as one (of several) modalities that showed promise in reducing symptoms of depression for patients with bipolar I or II (Yilmaz et al., 2022), and an independent systematic review also concluded that DBT has demonstrated efficacy in improving mood symptoms for individuals with bipolar (Jones et al., 2023). DBT skills training also appears to be efficacious in treating depression (see Delaquis et al., 2022 for meta-analysis and systematic review), including major depressive disorder (Turan & Akinci, 2022).

A pilot study of an ACT group treatment demonstrated improvement in quality of life and psychological flexibility, and reductions in anxiety and depression in patients with bipolar disorder I or II (Pankowski et al., 2017). One systematic review and meta-analysis of ACT’s efficacy in reducing depression demonstrated significant reductions compared to treatment as usual (Bai et al., 2020), whereas another demonstrated significant reductions in depression that were larger in magnitude relative to traditional CBT (Ruiz, 2012). Despite these promising results, CBT has a more robust evidence base in treating major depressive disorder relative to ACT or DBT.

Anxiety Disorders

A DBT-informed hospital program has been shown to reduce anxiety (Lothes et al., 2021), and appears to be beneficial in treating generalized anxiety disorder (Malivoire et al., 2020). DBT skills training also appears to be efficacious in treating anxiety symptoms (see Delaquis et al., 2022 for meta-analysis and systematic review). ACT also has demonstrated efficacy in reducing anxiety (see Gloster et al., 2020 for meta-analysis) and is considered an evidence-based method for treating mixed anxiety disorders (Hayes et al., 2012). Nevertheless, CBT presently has the strongest and more robust evidence base in treating various anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder (APA, Div 12, n.d.).

Substance Use Disorders

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, DBT was demonstrated to be more efficacious than treatment as usual (TAU) in treating substance use disorder, but was comparable to 12-step programmes (Giannelli et al., 2019). DBT delivered in a 12-week residential facility produced significant reductions in substance use severity and co-occurring psychopathology that were sustained across 10 years (Marceau et al., 2021). A recent study showed that DBT improved cognitive and executive function in people with substance use issues receiving methadone maintenance treatment (Khezrian et al., 2024).

A meta-analysis and systematic review have demonstrated ACT’s efficacy in treating substance use disorders (Gloster et al., 2020). One study demonstrated that ACT produced longer abstinence (vs. treatment as usual) and reduced depression and anxiety in patients with alcohol use disorder and co-occurring affective disorders (Thekiso et al., 2015). Again, despite promising outcomes in treating substance use disorders with DBT and ACT, CBT-based intervention has strong research support and the evidence base is more robust than the former two interventions (APA, Div 12, n.d.).

Personality Disorders

DBT is considered the preeminent treatment for BPD, suicidality, and non-suicidal self injury (Linehan, 2015; Stoffers-Winterling et al., 2022). In the most recent meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials evaluating psychotherapies for BPD, DBT emerged as one of two (the other being mentalization based treatment) that significantly reduced BPD symptoms and other co-occurring issues (Stoffers-Winterling et al., 2022). A pilot study found that a year of DBT reduced dysfunctional behaviours in a small sample of men with co-occurring BPD and antisocial personality disorder (Wetterborg et al., 2020).

A systematic review indicates that ACT produced significantly greater improvements in emotion regulation than treatment as usual for individuals withs BPD (Crotty et al., 2024). APA’s Division 12 considers DBT to have amongst the most robust evidence base and it is indeed considered the gold standard for treating BPD.

Eating Disorders

A systematic review of 13 studies indicated that DBT treatments modified to address eating disorder treatment targets appear to be effective in reducing eating disorder behaviours, including those consistent with binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa, while also addressing co-occurring disorders such as BPD (Bankoff et al., 2012). DBT skills training also appears to be efficacious in treating binge eating disorder and bulimia (see Ben-Porath et al., 2020 and Delaquis et al., 2022 for meta-analyses and systematic reviews). APA Division 12 notes that CBT tailored for binge eating disorder has strong research support, whereas neither DBT nor ACT are noted as an evidence-based treatment for this disorder. For anorexia nervosa, CBT has modest research support, as does a variation of DBT called ‘Radically Open’ DBT, which aims to improve social signaling and flexible responding (APA, Div 12, n.d.).

Trauma Disorders

A review (Lee et al., 2022) identified two studies exploring the effectiveness of DBT for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for adults who have endured childhood sexual abuse. Both studies (Bohus et al., 2013; Steil et al., 2011) found that DBT for PTSD, which involved multiple therapy sessions per week alongside additional skills training and group sessions, significantly reduced PTSD symptoms for these adults, who were residing in residential facilities.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of ACT’s effects on trauma-related symptoms demonstrated that ACT reduces trauma symptom severity and is more efficacious at doing so than treatment as usual (Rowe-Johnson et al., 2024). Despite promise from both DBT and ACT in addressing trauma-related symptoms, interventions that are strongly recommended by the APA are all CBT variations such as Cognitive Processing Therapy (APA Div 12, n. d.).

Physical Health Conditions

ACT has been shown to significantly reduce irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms, anxiety, and depression, and improve quality of life in patients with IBS, and was more effective in producing these outcomes relative to DBT (Taghvaeinia et al., 2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that, for individuals with chronic pain disorders, ACT improves pain-related functioning, pain acceptance, and quality of life, and reduces co-occurring symptoms of anxiety and depression (Martinez-Calderon et al., 2024). Another systematic review and meta-analysis including participants with a variety of chronic health conditions support ACT’s efficacy in improving overall and psychological health (Konstantinou et al., 2023). APA Division 12 has appraised ACT as having strong research support for its effectiveness in treating chronic pain issues (APA Div 12, n.d.).

Key Takeaways

| Presenting Concern | Treatment | ||

| CBT | DBT | ACT | |

| Depression | Strong | Modest | Modest |

| Anxiety Disorders | Strong | Modest | Modest |

| Substance Use Disorder | Strong | Modest | Modest |

| BPD | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Eating disorders | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Trauma Disorders | Strong | Modest | Weak |

| Physical Health Conditions | Modest | Weak | Strong |

Zooming In: Evidence Base for 2SLGBTQIA+ and Racialized individuals

When Linehan first created DBT, she embedded many aspects of feminist theory into her conceptualization, recognizing how systems of oppression function, and the stigmatization individuals with BPD in particular may experience (Linehan, 1993; Oshin & Rizvi, 2024). Nevertheless, earlier studies of DBT lacked ethnoracial diversity and did not always report on gender diversity characteristics (Oshin & Rizvi, 2024). Tides are turning, however, with a recent systematic review of how well-represented minoritized groups are in randomized trials of DBT demonstrating that ethnoracial minorities are increasingly being represented in DBT trials (Harned et al., 2022). The authors noted that the ethnoracial minority group inclusion in DBT trials has increased over time, with the present evidence base for DBT appearing to adequately represent these groups across ages and clinical populations. This same systematic review also observed that sexual minority groups are in fact overrepresented in DBT trials (relative to the U.S. population), and the percentage of sexual minority participants has actually increased over the past three decades of research on DBT (Harned et al., 2022). In contrast to ethnoracial and sexual minority groups, Harned et al.`s (2022) systematic review points to very limited DBT trials that included gender minorities. Nevertheless, in the two studies wherein data on transgender identity was collected, the proportion of participants who identified as transgender was disproportionately higher than the estimated rate in American adults. In summary, the current evidence, based on randomized controlled trials, supports the use of DBT with ethnoracial and sexual minorities, but more work is needed to confirm the same outcomes for gender minority groups.

ACT`s inherent flexibility, and overarching aim of enhancing individual psychological flexibility, has left it well-positioned to be of benefit to ethnoracial, sexual, and gender minority groups (Fuchs et al., 2013; Misra et al., 2023). A meta-analysis exploring the efficacy of ACT with diverse populations supported use with these groups (Fuchs et al., 2013). Misra et al.`s (2023) more recent systematic review of 75 randomized controlled trial studies indicated that whereas some ethnoracial groups (i.e., Black, Multiracial, and Native Americans) were well-represented in ACT trials, others (i.e., Latinx, Asian) were underrepresented. The relative under-representativeness of some of these groups makes it difficult to draw conclusions about ACT`s efficacy for these groups. Nevertheless, the systematic review does refer to studies with the majority of the samples comprising non-White ethnoracial groups, with encouraging results in treating psychological disorders for these groups (Misra et al., 2023). Authors of the systematic review note that, unfortunately, across the studies reviewed, there was sparse reporting on sexual orientation and gender identity. However, an independently conducted systematic review of evidence for the use of ACT specifically with 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals indicated that ACT increased overall psychological flexibility, reduced shame and minority stress, improved quality of life, and improved other symptomatology associated with eating disorders, depression, and anxiety for these groups (Fowler et al., 2022). These authors concluded that ACT aided in cultivating psychological flexibility in sexual and gender minority groups, which produced many positive changes for these individuals.

In summary, ACT, like DBT, appears to be a promising modality to address the psychological suffering of ethnocultural, sexual, and gender identity minority groups. However, also like DBT, more research is needed to understand nuances in treatment outcomes across these groups and any adaptations that might be useful. Fortunately, a strength of both DBT and ACT for minority groups is their contextualist theory, meaning that cases conceptualization and treatment planning is done in an individualized manner for each client and can therefore incorporate social identities that are relevant and important on a case-by-case basis (Misra et al., 2023; Oshin & Rizvi, 2024).

Spotlight on Atlantic Canadian Specialized Treatment Program Research

The Borderline Personality Disorder Treatment Program (BPDTP) in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia is a comprehensive treatment for individuals with BPD that began accepting referrals in 2012 (personal communication, J. Cohen, 2017). The BPDTP provides longer-term treatment (i.e., six months or more) to adults with BPD who have only marginally benefited from traditional community resources, have used a disproportionately high amount of health care resources, and are at high risk of developing even more severe forms of BPD without specialized resources (Nova Scotia Health, 2024). The program is based on DBT, and includes all core components of standard DBT, as formulated by Linehan, including individual therapy and group therapy sessions, a consultation team, and phone coaching during specified hours. Some clients also participate in a wellness and/or process groups, depending on clinical need.

Two scholarly articles have been published based on research conducted at the BPDTP. In the first, Doyle et al. (2022) investigated the importance of ‘anxiety sensitivity’ (AS) – a multidimensional dispositional tendency to have difficulty tolerated anxiety-related physical sensations – in predicting BPD symptom severity. They found that AS predicted BPD symptom severity over and above emotion dysregulation and impulsivity, both of which are theorized to be at the core of BPD symptomatology (Crowell et al., 2013). Doyle et al. (2022) also found that AS levels significantly decreased from pretreatment to 6 months posttreatment for participants at the BPDTP, suggesting that a DBT-based treatment reduces AS during the first six months, but interventions that explicitly target AS (e.g., CBT for AS, Watt et al., 2006) might be warranted for later stages of treatment.

In the second article, Doyle et al. (2023) investigated predictors of premature treatment dropout, defined as discontinuing treatment before six months, in participants at the BPDTP. They included both static (age, ethnicity, employment status, education level, number of co-occurring disorders) and dynamic (i.e., BPD symptom severity, emotion dysregulation, impulsivity, motivation for change, non-suicidal self-injury, insecure attachment) predictors in the statistical model to identify participant who did or did not prematurely drop out of treatment. Doyle et al. (2023) found that participants at the BPDTP who dropped out of treatment prematurely had higher pre-treatment levels of emotion dysregulation than those who stayed in treatment. The authors noted that elevated emotion dysregulation might lead to premature treatment dropout via aptitude to experience intense negative affect and deficits in regulating this affect, which then results in maladaptive efforts to regulate emotion, including prematurely suspending treatment to avoid discomfort. Doyle et al. (2023) suggest that clinicians might consider prioritizing distress tolerance and emotion regulation skills earlier in treatment for these clients to mitigate likelihood of dropout.

Summary

Both DBT and ACT fall under the umbrella of being a ‘third-wave’ cognitive behavioural therapy, meaning they both more explicitly incorporate acceptance, values, and emotions into the therapeutic landscape in addition to their behaviourist foundation of traditional CBT. Whereas DBT is more systematic and structured in its delivery, ACT is notable for its flexibility. DBT is based on the applied biosocial theory and ACT is based on the basic relational frame theory. At present, both modalities are widely practiced, and both have accrued a strong evidence base supporting their efficacy in treating a range disorders; however, of the two, DBT remains the preferred treatment of BPD, whereas ACT has a stronger evidence base in addressing chronic health conditions. Each show promise in addressing clinical concerns for individuals identifying as having diverse ethnocultural, sexual orientation, and/or gender identities, but continued research is needed to understand the nuances of treatment outcomes across these groups. Despite some differences in their theoretical sources and packaging, their aims ring strikingly similar – DBT endeavors to support clients in ‘building a life worth living’ and ACT hopes to help clients ‘get out of their heads and into their lives’.

Test yourself!

Media Attributions

- Wave 1 © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- wave 2 © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- wave 3 © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Biosocial theory of personality functioning © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- DBT house © Madison Conrad is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

A structured, skills-based cognitive-behavioral therapy focused on balancing acceptance and change, often used for individuals with emotion regulation difficulties.

A mindfulness-based behavioral therapy that promotes psychological flexibility through acceptance, defusion, values, and committed action.

Principles and beliefs that guide behaviour and provide meaning in ACT and DBT frameworks.

The active process of allowing thoughts and feelings to occur without trying to change or avoid them.

A core DBT concept emphasizes integrating two seemingly opposite or contradictory ideas, such as acceptance and change, in order to resolve therapeutic tensions.

The DBT-based theory that emotional vulnerability and invalidating environments interact to produce chronic emotion dysregulation.

The inability to flexibly manage and respond to emotions in a healthy way.

The practice of paying attention in the present moment with openness, curiosity, and nonjudgment, foundational in both DBT and ACT.

A DBT skill module aimed at improving one’s ability to tolerate and cope with intense emotions without resorting to unhealthy behaviours.

A concept in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) that means fully acknowledging reality as it is, without judgment or resistance.

A set of DBT skills which aims to aid clients in identifying, understanding, and regulating their emotions.

DBT skills designed to help individuals navigate relationships by balancing priorities, self-respect, and goals.

The philosophical foundation of ACT that focuses on understanding behaviour in context and its utility rather than its form.

A theory of language and cognition that explains how humans learn meaning by relating words, ideas, and experiences to one another.

A concept in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) where a person becomes entangled with their thoughts, treating them as literal truths rather than passing mental events.

The tendency to avoid or escape unwanted thoughts, feelings, memories, or sensations, even when doing so causes harm in the long run.

An ACT technique that helps individuals reduce the impact of thoughts by changing their relationship to them.

An ACT process of ongoing, nonjudgmental contact with psychological and environmental events as they occur.

An ACT concept referring to the observing self that is distinct from thoughts, feelings, or roles.

The ACT process of clarifying what is most meaningful to the client to guide behavioural choices.

Behavioural steps taken in alignment with identified values, even in the face of discomfort or obstacles.

The ability to stay in contact with the present moment and take values-based action despite difficult thoughts or emotions.