1

Chapter 1: Understanding Legal and Political Identity Discourses

Learning Objectives

- Understand the complexities of Indigenous identity in Canada, including legal and political aspects

- Analyze the impact of the Indian Act on Indigenous business practices

- Explore the significance of Indigenous identity and traditional governance in business planning

- Evaluate the role of UNDRIP in promoting Indigenous rights and business development

Chapter 1

Introduction:

Many textbooks present the basics of business studies and business planning processes without thoroughly discussing the relationship between administrative processes and government policies. In the context of Canadian businesses, for example, most text books either are edited copies of American Business texts or European (i.e. British or French) texts (Bryman et al., 2011)*MB CONFIRM CITATION. The texts often make some sweeping assumptions about legal and economic structures which would be covered in other courses. As a result of some of these foundational assumptions, business educators can overlook or ignore local and regional influences that impact business functions. For example, what differentiates a Canadian business from an American one? How does location of a corporate office or an employees workplace change the legal and political administrative obligations of the business? These questions about location and government rules received significant media attention in 2025. They are questions that highlight the need for business textbooks to recognize the ways in which tangible and intangible cultures, political systems, and legal rules influence business operations.

This text is designed to discuss some foundational business principles by focusing on the perspectives and lived experiences of Indigenous peoples working in various fields of business administration in a [1] * I forget how we were making notes. This will need a footnote or index item that explains: Canadian context refers to businesses with physical operations located in Canada while also recognizing the dynamics of Indigenous sovereignty which will be discussed later. Business studies, to date, have had limited engagement with Indigenous perspectives of business (Bastien, Coraiola, & Foster, 2023) and yet, we can learn a lot about business strategy, economics, and innovation by understanding how Indigenous businesses operate. At the same time, learning about and from Indigenous businesses, students will also gain insight into and discuss how Canadian cultures, government systems, and legislation apply in different locations and with cultural and social identity groups.

Foundational Assumptions of Indigenous Business

In this book we start with an introductory discussion about economics and economies of place (or place based economies). A simple definition of the word economy or economic systems as the processes involved in production and exchange of goods and services. This definition includes a wide variety of production, processing, and means of exchange that are valued or measured using local currencies and principles of international exchange. When economics are discussed in mainstream Canadian (and global) discourse, we often assume to be referring to capital economics. (e.g. values are measured by using Canadian dollars as the assumed currency.) When a retailer exchange goods with American’s, the Canadian dollar and American exchange rate will be applied based on application of larger economic levers and policies enforced by the national banking systems.

Often, it is fair to assume that when talking about economic system that the capital economic system, which is why business educators focus on them. But they may not discuss other forms of economic exchange in depth, and they may not explain the relationships between government policies, sovereignty, and economics. It is these topics, however, that provide the answers to the questions about how Indigenous and Canadian businesses differentiate themselves in global markets. The points of differentiation go beyond how and where businesses are registered or who collects corporate taxes. Indigenous businesses, including those profiled in this text, are evidence of economic systems that emerged from and for the space that we now refer to as Canada. They demonstrate cultures and traditions and legal and political systems that are ancient and current (modern). Embracing Indigenous knowledge systems, identities, and Ways of Being and Knowing into business planning is an opportunity to honour the wisdom of the Indigenous cultures.

These other elements of culture, language, political systems, and legislative oversight, are discussed and considered in this text. Each of the chapters is an overview of and a primers for bigger discussions that will help us to think through some ways Indigenous identity might influence Indigenous business. The course materials and cases are a chance for the classes to explore how the teachings can be utilized and operationalized in a business context.

Historic Context of Modern Indigenous Business Models and Canada-Indigenous Relations

Before proceeding too far into an exploration of ‘Modern’ Indigenous Business Models, it is important to review Canada’s history through an ‘Indigenous’ lens. Each Indigenous community has their own creation stories and ways of understanding the world. Their stories are rooted in, tied to, informed by the geographic places, languages, and traditions. These stories and knowledge systems are thousands of years old, and they are the basis of Indigenous sovereignty claims presented today. Indigenous ways of knowing and being refer to models of governance, law, and knowledge transfer. Given the limitations around how much depth and detail can be included about each Indigenous community in Canada, this section of the text presents a perspective from Mi’kamw’ki Atlantic Canada. It is appropriate to start with Atlantic Canada because this book originates in Mi’kmaw’ki/Atlantic Canada, and the author identifies as Mi’kmaw/Canadian. It is also the most easterly part of Turtle Island and has some of the oldest stories of colonial encounter.

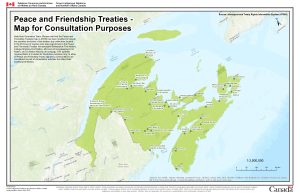

** Figure 1. Interactive Map of Indigenous Territories. Source: Native-Land.ca ** CONFIRM FORMATTING IS CONSISTENT FOR FIGURES AND IMAGES>

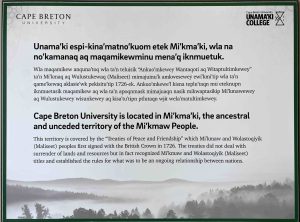

It is common practice within many regions of Canada to recognize the territorial history by either doing a land acknowledgement, treaty acknowledgement, or territorial acknowledgement. Each form of acknowledgement has different political and legal meanings, but have a similar intent, to recognize the complexity of space and identities. For example, at Cape Breton University there are land acknowledgements posted throughout campus and the same acknowledgement is read at the beginning of formal gatherings.

“Mi’kma’ki, known today as Atlantic Canada, is the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq People. This territory is covered by the Treaties of Peace and Friendship, which Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) people first signed with the British Crown in 1726 [Update with more details about the years the P&F Treaties were signed]. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1360937048903/1544619681681 The treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources but in fact recognized Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations.”

While these acknowledgments stand as reminders of the past, when read in class or at meetings, they are also expanded with a challenge to reflect on and discuss their ongoing relevance today. The Treaties of Peace and Friendship are among some of the oldest treaty agreements, they predate the formation of Canada, and are considered among a group of treaties referred to as “Historic Treaties.” This category of treaties refers to the agreements made before the British North America (BNA) Act was passed in 1867, as the first constitutional document of Canada. Treaty agreements made after 1867, and before the 1970’s, were sequentially numbered, for the most part, and thus are referred to as “Numbered Treaties.“ The regions covered by the numbered treaties cover most of provincial areas known today as Manitoba, northern Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Any treaties and land claims negotiated with the government of Canada after the Constitution Act, 1982, was passed (an update to the British North America act) are described as “Modern Day Treaties.”

Each treaty covers a specific region. The territorial acknowledgement presented in Cape Breton explains the relevant treaty, the signatory parties, and the date. These specific details have significant legal and political implications for businesses and organizations. When and if they are to be contested or interpreted in a judicial process, the legal representatives of Indigenous parties explain that Mi’kmaw inherent rights to hunt, fish, self-govern, earn a moderate livelihood, must be understood a inherent legal rights because the treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources. Further, anyone wishing to make use of or to extract value from lands and resources, must negotiate with (consult) Mi’kmaw governments.

Their position has been tested by the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) who have reinforced their claims and this interpretation of the treaty agreements. Further, Canadian governments are expected to honour these agreements made with the British Crown because Canada’s sovereignty claims continue to rest with the relationship formed with the crown. Note this is one way in which Canada’s history politically and economically distinguishes itself from that of the United States. Canada inherited their sovereignty from the British Crown, where the United States of America won their independence from the British Crown and cut ties to them.

- Find a video online describing the treaties and when they were signed. AND/OR Insert a map that shows the treaties (e.g. Native-Land.ca | Our home on native land)

- Recommended activity – Encourage students to identify the treaty territory they reside in currently, where they grew up, or where their favorite businesses are located.

Treaty implications on identity (and identity politics)

A general overview of the political and social identities and their meanings is described below. The ways in which they are currently defined (ie. Indigenous self-identified or as Indian Act identity) has implications for individuals and their business planning strategies.

Before proceeding to learn about Indigenous Business and enter discussions about or with Indigenous communities, it is useful to think about the aspects of our personal identities and how they influence our social interactions. In this section we refer to tools developed by the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) for their health research teams. They include the culturally relevant gender-based analysis (CRGBA) Research toolkit (NWAC 2022) (LINK TO ONLINE WEB SOURCE).

NWAC encourages anyone working with Indigenous Communities to continually be aware of their own positionality by fostering reflexivity. They provide guidance through example activities such as the intersectionality map (NWAC 2022) ( INSERT LINK TO ONLINE WEB SOURCE or IMAGE OF INTERSECTIONALITY MAP). Intersectionality tools help individuals reflect on the intersecting dimensions of social identity. Indigeneity is one aspect of whole complex people. Other aspects that shape a person’s view of the world around them include things like physical ability, age, sexual orientation, gender, as well as experiences in past such as the places where one lived as a child and where/if they attended elementary and secondary schools.

These aspect of personal identity change the way we make sense of things and situations today. Continuing the discussion of identity, a common aspect of Indigenous teachings presents the topic of relationality. *CREATE A TERM or link to a Glossary TERM In CHAPTER 1** The significance of relationality is evident as you explore intersectional identity webs. As you reflect aspects of identity, you will likely begin to remember significant events that shaped how you interact with peopel today. Your family dynamics and community dynamics from your youth, for example, are likely where you first start to learn about personal and community values. Did you spend time alone, at community events, indoors or outdoors?

Exploring Personal Intersectionality Exercises

ACTIVITY 1A: USE INTERSECTIONALITY MAP AS A GUIDE TO REFLECT ON CORE ELEMEBTS OF EACH STUDENTS PERSONAL IDENTITY .

Debrief with the class.

ACTIVITY 1B: INTERSECTING WITH PLACES AND PAST EVENTS

Invite students to think about their favorite places. What do they do in these places? What do they love about them? Students sometimes reflect on outdoor spaces (the woods, a park, a beach) or indoor spaces (sports arenas, gyms, art studios). They may say that it is their favorite place because it has positive memories, or because it allows them to connect to others (people, team mates, friends, animals, trees, water, etc.)

The break out exercises 1 a and b provided demonstrate how aspects of identity and values shape individuals beliefs about the world. They also affect one’s approach to their professional lives and professional relationships. For students studying Indigenous-business, for example, they are entering a classroom community motivated by an academic or professional goal. The segue here is to assume that students in the class want to learn about Indigenous Business, but each student has a personal motivation for being there. Is it a core requirement or an elective? Are you intending to get a business degree or an Indigenous Studies degree or something else? Do you have pre-existing relationships with Indigenous peoples or communities? How close are those relationships? Are there questions you have coming into the class that you hope to answer?

– Group activity to share thoughts and motivations in classrooms.

The Past and Histories. The maps above provide a sense of Indigenous territories and national boundaries. They demonstrate the physical and geographic space occupied by Indigenous nations since time immemorial [Glossary TERM], and the relationship between spaces, places, and cultural groups (differentiated from one another linguistically, politically, and economic traditions).

When trying to understand the formal and informal rules and norms of Indigenous business today it is important to have a general sense of the historical context of Canada-Indigenous relations. The historical context of the relationship refers to the histories of Indigenous nations that pre-date settlement, and the histories of Canada’s settlement, establishment of confederation, and sovereignty. The complexity of treaties also reflects how different regions, and regional governments, negotiated with settlers. Thus history has significant influence on why and how Indigenous people self-identify. The words they use also reflect the complexity of rules the governments use to identify citizenship. These are both important to understand as there are legal and access implications for each.

Word Matters. It can be difficult to understand Indigenous identity in Canada. There are a lot of words that have similar but specific meanings. For example, in this text we primarily use the term Indigenous referring to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP or The Declaration). (Government of Canada, 2020). In Canada, we also have Indigenous rights affirmed legally in section 35 of the Canadian Constitution. But they do not use the term “Indigenous” instead this legal document uses the term “Aboriginal” which refers to First Nations (Indians), Metis, and Inuit peoples. Although the term Aboriginal is socially recognized as derogatory, it continues to have legal relevance.

HISTORY OF CANADA INDIGENOUS ECONOMIC CHANGES

This brief history in this section highlights significant political and legal events from the past that continue to serve as touchpoints for Indigenous-led organization studies. For anyone working with and for Indigenous organizations, the events present the history of changes in the Canada-Indigenous relationship and formative context for current reconciliation efforts. Although the terms used change over time (Indian, Aboriginal, Indigenous) and may be unfamiliar to students, many of these terms are legally and political relevant for Indigenous businesses and Canada-Indigenous reconciliation.

Germinal Legal and Political Reference points of Aboriginal Economic Development

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal People (RCAP, 1996) [INDEX – GLOSSARY] is a jumping off point for this review. The RCAP report – a five-volume report produced between 1991 and 1996 – continues to be an important policy reference point in the field of Indigenous business and economic development. It punctuates significant political and legal events from the past that continue to serve as touchpoints for Indigenous-led research today (Graham & Newhouse, 2021; Voyageur, Newhouse & Beavon, 2011).

Canada is a colonial nation. A significant part of the colonization process starting in the 16th century involved settlement (establishment of permanent residences for European settlers) and treaty making with Indigenous nations (See treaty table), and institutionalization of European values.

I refer to the final report of RCAP (1996) because it structured a story of the past relationship between Canada and Aboriginal peoples into four temporal periods which I review below. They are: (1) Separate worlds (Before 1500), (2) Contact and Cooperation (1500s – 1867), (3) Displacement and Assimilation (1867 – 1969), and (4) Negotiation and Renewal (1969 – 2016) (RCAP, 1996). Arguably, we are now in a fifth period that may be called Truth and Reconciliation (2016 – future).

The TRC [INDEX – GLOSSARY] also produced historical records as part of their mandate. The TRC reports (e.g. They Came for the Children, 2012 and What we have learned, 2015), identify significant events, actors, and policies. They proceed to describe the relationship between “the growth of global, European-based empires and the Christian churches (What we have learned, 2015, p. 15).”

Separate Worlds (Before 1500): Sovereign Nations before European arrival

In RCAP, the period prior to 1500s was described as separate worlds, Aboriginal societies in the Americas and non-Aboriginal societies in Europe developed in entirely different geographic spaces, in ignorance of one another. It is a period that shall not be presented as a historical void for the territories we now refer to as Canada. Indigenous societies who occupied the space had regional governments and traditional territorial boundaries that spanned the continent. There was also variety in their languages, cultures, and social traditions. Historically, from an Indigenous perspective, Indigenous peoples are groups of self-governing societies with traditional languages, teachings, and ways of organizing, that have developed since time immemorial. Referring to the period before European settlement of Canada refers to a time when Indigenous nations’ relationship to places were not questioned. The relationship between Indigenous societies and place was engrained in social norms/laws and reflected in the language (McMillan, 2020).

In the last chapter I referred to two concepts of an Indigenist research paradigm – relationality and relational accountability – because they direct us to explore localized Indigenous teachings that derive from Indigenous relationships with local spaces. In Unama’ki/Breton, where I live, the Mi’kmaw nation was a sovereign, self-organizing, political, whole system of knowledge. Traces of the past are found in stories, place names and the language of Mi’kmaw’ki/L’nu. Mi’kmaw origin stories speak of people who sprang from this place (Sable & Francis, 2012). Modern Mi’kmaw governance structures rely on traditional legal concepts that translate into the modern sense of jurisdictional authority (Denny, 2022). The concept of Netukilimk, for example, refers to the responsibility the Mi’kmaw must live in a symbiotic relationship with land, earth, and the environment (McMillan and Prosper, 2016).

Mi’kmaw is among the many Indigenous nations of what is commonly referred to as North America and were vibrant, politically sophisticated, and economically active societies. When Indigenous leaders talk about returning to a nation-to-nation relationship (RCAP, 1996; TRC, 2015) or inherent rights (Canadian Constitution, 1982; TRC, 2015), they are referring to the sovereign nations and political and legal orders that pre-date European settlements in the territory. There were complex models of exchange and trade (i.e., economies) that functioned in this space within and between nations (MacLeod, 2016, Voyageur et al, 2011) such that traditional Indigenous trading routes of the period were the foundation of the fur trade (Heber, 2011).

Contact and Cooperation (1500s – 1867)

The next historical period is defined by the events of first encounter between Indigenous societies, European settlers (citizens of primarily France and England), and official representatives of the British or French Crown (e.g., military leaders, religious leaders, and political delegations). Contact refers to the new contacts that were made between those societies who had not been aware of one another, let alone in contact with one another. In the 1500s the encounters between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal societies began to increase in number and complexity (Heber, 2011; Newhouse, Voyager, & Beavon, 2005). The period spanned over 300 years, and generations of families. It witnessed significant economic events, including the establishment of military outposts (e.g., Fortress of Louisburg, locally), trading posts (e.g., Hudson’s Bay Company, Northwest Company), the Royal Proclamation (1763), the War of 1812, and the American Revolution.

The period is characterized as contact and cooperation in reference to the nature of many of the inter-societal interactions between and among treaty partners and political allies. The political agreements were negotiated between governments to clarify how the places their citizens occupied would be managed. Treaties were formed with settlers representing the crown, the church, and the state (Battiste, 2016; Borrows, 2017; Morin, 2005). The treaties allowed for social, economic, and political relationships to develop that became the foundation of the modern Canadian economy. A list of treaties in chronological order is provided in Brown et al (2016, p. 292). During the period in which the historic treaties (e.g., Peace and Friendship Treaties) and numbered treaties (i.e., Treaties 1-11) were signed, Indigenous societies were recognized as independent self-governing groups with sovereignty in their homeland. This counternarrative undermines the basis of claims through which European governments claimed sovereignty in the space commonly known as Canada’s baseline colonial policy, the Doctrine of Discovery (Borrows, 2017; Canada, 1996).

Displacement and Assimilation (1867 – 1969): Canada’s Indian Act Approach

The British North America Act (BNA) of 1867 ushered in a new political relationship between nations and with it the Indian Act of 1876. Together they signified the beginning of confederation processes for European settler colonies and governments. The Canadian TRC referred to the Indian Act as a policy of cultural genocide established as part of the BNA, a policy of the British sovereign that claimed rights to territory, and the pre-cursor to the Canadian Constitution Act of 1982. The construction of Indian Act policies, based in these assumptions, disenfranchised Indigenous peoples from their claims to tradition, culture, and sovereignty in their homelands.

I think of this period as a shift toward colonial denial. It is defined by the implementation of new settler-colonial laws. The new laws informed a new idea of Canada (the state) that was dependent on the delegitimization of local Indigenous societies. Once the BNA was in place, the Federal Government’s approach to Indian affairs replaced Indigenous leaders’ sense of sovereignty and agency with dependency. Multiple amendments gradually increased the power of Indian Agents and diminished the relative power of Indians to resist enfranchisement (Cardinal, 1969). It was a systemic approach that, over decades, became more pervasive through policy development and militarization.

There are several select events (see Table 3-1) that represent a relationship between the colonial government’s approach to Indian Affairs that treated “Indians” as incompetent wards of the state. They include implementation of policies (e.g., gradual enfranchisement, encroachment in places, resource exploitation, and militarization) and court decisions that reinforced the legitimacy of their actions, at least from the perspective of Eurocentric legal principles (Borrows, 2017). Among these many regionally specific and national policies, was the Indian Residential School (IRS) policy.

Indian Residential Schools were one aspect of cultural assimilation and cultural genocide. Canada’s Indian Residential School System was a nation-wide federally funded program. The expressed goal of the system was to (re-)educate Indigenous children (then referred to as Indians) by disenfranchising them from their families, communities, and traditions (Battiste, 2013). The Indian Residential School policy, like so many policies managed by the Federal Department Indian Affairs was designed to eradicate Indigenous cultures and languages, through systems that promoted neglect for human dignity. The operation of Indian Residential Schools spanned years between 1867 – 1998, but the peak recorded annual enrollment was almost 12,000 children in the 1950s spread across roughly 90 schools.

Many “students” who attended these schools were treated terribly. They were subjected to physical and emotional violence. We now have evidence that thousands of children died in residential schools, and hundreds of them were buried in unmarked graves on the school sites2. Like all other federal policies that derived from Indian Act, administrative oversight for the national program was delegated to the Department of Indian Affairs who then outsourced the administration of the “schools” to religious institutions. The Federal Government was ultimately responsible for continued funding of administration and the supply of students to them (MacDonald, 2007; MacDonald and Hudson, 2012), thus it was also responsible for the harms endured by those who attended them.

Indian Residential Schools and the White Paper Policy. Most of the Indian Residential Schools were closed during this period too. The closures reflected a change in the federal government’s Indian Residential School approach. By the 1950’s the Indian Affairs education system lacked the money and resources required to support the segregated school system, and modified The Indian Act so that First Nations students could attend public schools. The move to transfer students from church run schools to provincially run public schools temporally coincided with the release of the federal government’s White Paper on “Indian Policy” which “… proposed a massive transfer of responsibility for First Nations people from the federal to provincial governments. It called for the repeal of the Indian Act, the winding up of the Department of Indian Affairs, and the eventual extinguishment of the Treaties (What we have learned, 2015, p. 40).”

Negotiation and Renewal (1969 – 2016): Indigenous- led united resurgence in Canada

The final period RCAP identifies started around 1969, referring to the White Paper (Canada, 1968), and corresponding response, the Red Paper (Cardinal, 1970). Negotiation refers to the prevalence of legal and political responses to Indigenous advocacy which eventually led to a re-negotiation and recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights. Three watershed events are recognized as shaping this era of Native activism in Canada (Coulthard (2014): (1) The militarization of First Nations’ opposition to the 1969 White paper described as, “an unprecedented degree of pan-Indigenous assertiveness and political mobilization.” (p.5); (2) The Calder decision in 1973 that launched a series of discussions regarding Aboriginal title to land that existed prior to settlement; and (3) series of events related to the energy crisis and the oil crisis of the 1970s that were also related to unresolved issues of Native rights.

I think of the 1970s and 1980s as a period of defined by Indigenous-led peaceful political resistance and leadership leveraging their power through diplomatic assembly. Multiple Aboriginal advocacy organizations were established regionally and nationally. The National Indian Brotherhood, the precursor to the Assembly of First Nations, was established in 1967 and incorporated in 1970. The Native Women’s Association of Canada was established in 1974.

Resisting government policy and seeking justice: The origins of the TRC. The Oka Crisis of 1990 was one of the most notable and relevant to consider the intersection between economic development and reconciliation (Meng, 2020). From a lens of economic development, Oka represents the plausible implications of failing to consult Indigenous nations before launching new developments in their territories. It also marked a turning point in terms of reconciliation because the fall out of the standoff between the land defenders and Canadian military, prompted the launch of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (Barsh, 2005; Regan, 2010).

In the 1990’s the Canadian justice system that historically supported values of colonialism began ruling in favor of Indigenous rights (Cassidy, 2005, p. 38) and challenged federal policies to change. If the government refused to acknowledge the truth about the systemic nature the Indian Residential Schools and controlled the narrative in public Canadian places (Regan, 2010), Aboriginal peoples continued to resist and seek justice through public measures. While leaders of federal government and church institutions continued to deny their legal accountability for the residential school system as a whole, individuals in local churches had begun to acknowledge the harms that some individuals and communities suffered because of the schools. The series of apologies offered in the 1980s and 1990s from religious officials and church representatives are listed in Appendix of TRC’s Executive Summary TRC, (TRC, 2015, p. 378). The church apologies that span 1986 – 2015, further evidence of the scope, scale, and impact of the Indian Residential School Programs on local communities. In the same period, student survivors increasingly turned to the justice system as a means of seeking reparations for damages.

With respect to reconciliation, the period following RCAP also saw the launch of the 1998 Exploratory Dialogues, and the process of Alternative Dispute Resolution Process, and the birth of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF). Taken together, this series of events increasingly affirmed Indigenous rights, and legitimized the truth of survivor stories. Because the TRC mandate was established as part of the Settlement Process, the legal context of negotiation presented salient cues for framing of the localized TRC discourse (James, 2022) discussed below.

The launch of the TRC coincided with the Federal Public Apology for the Indian Residential Schools. On June 11, 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada delivered an official “Statement of Apology – to the former students of Indian Residential Schools” (TRC, 2015, p. 369). The apology, in theory, would represent an end to the government denial. And, while it is beyond the scope of the analysis here, it raised important new cues for the Canadian public and Indigenous peoples. The government apology could not be compelled through the Settlement Agreement and was therefore considered a strategic political decision/announcement (Niezen, 2010).

Truth and Reconciliation (2016 – future)

I contend we have entered a fifth period that may be called Truth and Reconciliation for three reasons: (1) the RCAP (1996) laid out a 20-year strategy presented as the foundation for a renewed relationship; (2) the publication of the TRC’s final report was issued two decades after the RCAP report (Graham and Newhouse, 2021); (3) the TRC process appears to have changed the discourses of reconciliation and may have also marked a shift in the dynamics of negotiation and renewal that were imagined in RCAP; and (4) while many people were looking to the TRC for guidance about reconciliation (e.g., Craft and Regan, 2020) many have taken a longer view of reconciliation referring to the on-going implications of RCAP (Graham and Newhouse, 2021; Hughes, 2012; Regan, 2010).

Conclusion: Historical Discourses, Silences (policy gaps), and CRGBA

It is not a secret that Canada is a colonial state. The ties between the Canadian Government and Canadian cultural identity are closely tied to the British Government and the Commonwealth. And yet, the idea of settler colonialism is often presented as a part of the distant past of Canada’s formation and not as a modern ongoing project of maintaining Canadian power and legitimacy in sovereign Indigenous territories. Canadian social systems were, in fact, intentionally designed to erase Indigenous peoples, or at least their social structures and rights. The literature review in this chapter highlights germinal points that explain the integrated and deliberate political institutional strategies that were designed to prevent them from acting as self-governing nations and to diminish legitimate Aboriginal claims to self-government. The brief history above highlights cues that continue to be important to the modern Crown-Indigenous relationship and therefore the discourse of Canada-Indigenous reconciliation. This chapter represents one of the steps that is necessary in the reconciliation process – listening to, and learning from, Indigenous people’s perspective of the past. It is also the second step in the Two-Eyed CSM analysis, positioning my research question in the context of the communities with whom I study and work.

It was clear in the TRC reports that these foundational legal and political Crown-Indigenous and Nation-to-Nation relationships must be reconciled. It was also clear that these were not the only relationships that mattered. I focus on the TRC case study to consider whether and how these cues from formative context influenced the work of Commissioners as administrators. The line of questioning I follow in this thesis asks how the Commissioners made sense of the discourses in order to enact reconciliation-oriented change. And, to what extent were their choices helped or hindered by other related processes outlined in the Settlement Agreement that potentially conflated the meaning of truth and/or reconciliation?

The historical review helps to identify policy gaps and reinforces the value of the CRGBA framework. It clarifies the reasons CRGBA prioritizes the need to account for politically distinct identities, i.e., distinctions-based policy, and to be trauma-informed. In the next chapter, I will review the goals set out for the TRC. They were extensive, complex, and ambitious (James, 2022; Nagy, 2014; Stanton, 2017). I use questions presented in the CRGBA framework to evaluate the extent to which the TRC was designed to be culturally relevant to Indigenous claimants (former IRS Students and their families) drawing on the resources provided (NWAC, 2020, 2021, 2022).

Self-Governance and Indigenous rights. L’nu is the term the Mi’kmaw use to describe themselves as Indigenous people. It means “the people.” Beyond L’nu identity and cultural values, each person is comprised of other identities (class, race, gender etc.), personal values, views, and one’s location in space and time (Native Woman’s Association of Canada, 2022). All of these considered together comprise one’s positionality and inform the way one understands and experiences the world as well as the kind of knowledge one accumulates and shares.

The Constitution Act of Canada, Section 35 (1982) reaffirms the rights of Aboriginal people (Metis, Inuit, and First Nations), now commonly referred to as Indigenous people. The UN Declaration on the Right of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) received Royal Assent in Canada on June 21, 2021. It provides a roadmap for the Government of Canada and First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples to work together to implement the UN Declaration based on lasting reconciliation, healing, and cooperative relations (Government of Canada, 2024). UNDRIP affirms and sets out a broad range of collective and individual rights that constitute the minimum standards to protect the rights of Indigenous peoples and to contribute to their survival, dignity and well-being (Department of Justice Canada, 2020).

Indigenous Identity and the Indian Act. Although the Government of Canada has made efforts towards reconciliation, Indigenous identity is a complex and layered issue due. The Indian Act, which came into power in 1876, continues to influence modern Canadian-Indigenous policies and structures. The Indian Act was created to “control and assimilate Indigenous peoples and their communities (Native Women’s Association of Canada, 2022) and “allows the government to control most aspects of aboriginal life: Indian status, land, resources, wills, education, band administration” (Montpetit, 2011).

Figure 3. Video Link to Youtube.

| Period of time | Significance of the period | Years | Event/Report |

| Period 1

Pre-Settlement (… – 1671) |

The sovereignty of Indigenous nations was unquestioned. E.g., the Mi’kmaw nation was sovereign, self-organizing, political, whole systems of knowledge. Traces of the past are evident in stories, place names, the language of Mi’kmaw’ki/L’nu.

RCAP (1996) Referred to the period before 1500 as separate worlds. |

1372 (?) | Oral Histories |

| 1493 | Roman Catholic Papal Bulls

Doctrine of Discovery |

||

| 1497 | John Cabot contact Mi’kmaw | ||

| Period 2

Early Period of European Settlement and Treaty Making (1671 – 1866) |

Treaties were formed with settlers representing the crown, the church, the state. E.g., in Mi’maw’ki Chain of treaty agreements that spanned 1725-1779 (Marshall and Battiste, 2016).

(Brown et al, 2016, p.292)

Stage 2: Nation-to-Nation Relations Encounters between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people began to increase in number and complexity in the 1500s. |

1672 | Est. Hudson’s Bay Company |

| 1716-63 | Peace and Friendship Treaties | ||

| 1725-1779 | 1763 Royal Proclamation

1776 Est. North West Comp. |

||

| 1812 | Selkirk Settlers Reach Winnipeg

War of 1812 |

||

| 1850-54 | Robinson Treaties | ||

| Period 3

Treaty Making and Denial Establishment of Legal Foundations of Canada (1867 – 1968) |

Indian Act 1867 – “The Indian Act facilitated a strategy of assimilation through incarceration (McMillan, 2018, p.85)”, multiple gradual amendments, increased the power of Indian Agents, and diminished the relative power of Indians to resist enfranchisement.

Stage 3: Respect Gives Way to Domination In the 1800s, the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people began to tilt on its foundation of rough equality. The number of settlers was swelling, and so was their power. As they dominated the land, so they came to dominate its original inhabitants. |

1867 | BNA Act a.k.a Constitution Act (1867)

Indian Act Act of gradual enfranchisement 1869

|

| 1870 | 1870 Manitoba Act | ||

| 1871 | 1871- 1929 Numbered Treaties #1-11 | ||

| 1912 | Exchequer Court removes Membertou | ||

| 1928 | King v. Sylliboy | ||

| 1967 | The Hawthorn Report A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada

The National Indian Brotherhood forms |

||

| Period 4 a

Organized National Political Resistance (1969 – 1989) |

From the 1960s onwards, many people within churches began to re-evaluate both the broader history of the relation between churches and Aboriginal people, and the specific history of residential schools.

Multiple Aboriginal advocacy organizations were established Regionally and Nationally (e.g., NWAC, Urban Friendship Centres, Indian Brotherhood, Union of NS Indians).

Stage 4: Renewal and Renegotiation Resistance to assimilation grew weak, but it never died away. In the fourth stage of the relationship, it caught fire and began to grow into a political movement. One stimulus was the federal government’s White Paper on Indian policy, issued in 1969. |

1969 | The white paper policy

Harold Cardinal’s Red Paper (ref. Manuel, 2017, p. 95) |

| 1970 | The National Indian Brotherhood forms | ||

| 1972 | National Association of Friendship Centres https://nafc.ca/about-the-nafc/our-history | ||

| 1973 | Calder Decision (1973) | ||

| 1974 | Native Womens Association of Canada Established | ||

| 1975 | World Council on Indigenous Peoples, 1975 | ||

| 1977 | Berger Report 1977

Lysysk Report 1977 |

||

| 1982 | Constitution Act, 1982 (was BNA Act, 1867)

First Assembly of First Nations held |

||

| 1983 | Canada, House of Commons, Report of the Special Committee, Indian Self-Government in Canada (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1983).

1983 Marshall decision |

||

| 1985 | Report of the Task Force to Review Comprehensive Claims Policy, Living Treaties: Lasting

Agreements (Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1985); |

||

| 1986 | apologies issued by United Church of Canada in 1986 –1986 Royal Commission of the Donald Marshall Jr. Prosecution 1986 (Hickman, Poitras, and Evans, 1989). | ||

| Period 4 b

United Political Resistance/resurgence Legal affirmations of Indigenous rights (1990 – 2005) |

Political resistance and resurgence. Increasingly legal decisions were being made in favor of Indigenous rights.

Formal dialogues developed around political reconciliation of Aboriginal rights and Indian Residential Schools. |

1990 | Nunavut Land Claim

Sparrow Oka CANDO |

| 1991 | Launch of Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples | ||

| 1992 | BC Treaty Commission (1992) | ||

| 1996 | Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples release Report (1996) | ||

| 1997 | Delgamuukw Court Case | ||

| Jan. 7, 1998 | Statement of Reconciliation

Gathering strength: Canada’s Aboriginal Action Plan |

||

| 1998 – 1999 | Principles developed by the Working Group on Truth and Reconciliation and of the Exploratory Dialogues | ||

| 1999 | Aboriginal Finance Officers Association of Canada (AFOA) Formed | ||

| Alternative Dispute Resolution Program (2004) | |||

| 2001 | Multiple lawsuits filed by Oct. 2001 | ||

| 2004 | 2004, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled Cloud v. Canada (Attorney General) 2004 CanLII 45444 (ON CA). | ||

| Period 4 c

Truth and Reconciliation (2006 – 2015) |

2006 | Mandate Statement (2006)

Federal Apology (2006) |

|

| 2007 | Statements of Resignation

Public Media Reports |

||

| 2008 | TRC Launches | ||

| 2012 | They Came for the Children (2012)

TRC Interim Report (2012) |

||

| 2015 | TRC Final Report(s)

1 – 6 |

Table 1. Timeline of significant political and economic events.

Business implications of Treaties and Indian Act policies

The Indian Act created reserves on which there are policy rules that only apply to “Indians” as defined by the Indian Act. If Indigenous peoples refer to themselves as either “status” or “non-status,” Indians, it is because not all people who might identify as “Indian” or Indigenous have recognized status according to the rules set by the Government of Canada. It is often necessary to note that these identity distinctions because there are sets of rules in Canada that apply differently depending on the location of the business either on-reserve and off-reserve. Though problematic, the arbitrary boundaries the reflect which level of government has jurisdictional authority directly impact the types of funding and programming that Indigenous individuals are eligible to receive.

Indigenous sovereignty. The recognition of the rights of Indigenous People to be self-determining and self-governing in their homeland, the Government of Canada has committed to working though an added layer of complexity. It adds a fourth or fifth level of governments to include in discussion and creates messy boundaries for otherwise organized and bounded Canadian Jurisdictions. For example, an assertation of Mi’kmaw traditional governance systems and sovereignty through family lineage. (i.e. Indian Act band leaders invoke colonial legal systems as jurisdiction) versus traditional system (Elders summon their traditional systems – traditional governance lens and as such, revert to a treaty agreement).

Contrast the way the Indian Act identifies and categorizes Indigenous people, is the ways in which Indigenous people self-identify which is through family tradition and community practice (Kesler, 2020). The Indigenous constructs of being, knowing and relationality are not reflected in the rules that are currently used. For example, here in Mi’kmaw nation citizenship and claiming Mi’kmaw identity is tied to community identity such as clan, family, or traditional nation often with strong spiritual connection to place and cultural traditions. Thus, the question continues about what citizenship refers to and mean both for government and for Indigenous communities and individuals.

Indigenous identity and traditional governance in business planning

TO DO INSERT CONTENT FROM ENTREPRENEURESHIP

UNDRIP reinforces Indigenous rights and business development (Global implications)

TO DO INSERT CONTENT

Key Terms

- ADD ANY KEY TERMS WERE HIGHLIGHTED IN YELLOW ABOVE.

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Indian Act |

A Canadian federal law that governs matters pertaining to Indigenous peoples, including their lands, resources, and governance. It has significant implications for Indigenous business practices. |

|

Indigenous Business Practices |

Business activities and operations that are carried out by Indigenous peoples, often influenced by traditional values, governance structures, and legal frameworks such as the Indian Act. |

|

Indigenous Identity |

The complex and multifaceted sense of self that Indigenous individuals and communities hold, which includes aspects of culture, heritage, legal status, and community ties. |

|

Intersectionality |

A framework for understanding how multiple social identities (e.g., race, gender, class) intersect to create unique experiences of discrimination or privilege, particularly relevant in analyzing Indigenous identities. |

|

Reconciliation |

The ongoing process of acknowledging and addressing historical injustices and harms done to Indigenous peoples, with the aim of fostering improved relationships and equality. |

|

Self-Identification |

The process by which individuals or communities define their own identities, as opposed to identities imposed by external entities or governments. |

Discussion Questions/Activities

TO DO LATER – CREATE QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES

Explore the significance of Indigenous identity and traditional governance in business planning (ACTIVITY?)

National Indigenous Leaders and Organizations are working to provide additional guidance to governments of Canada and clarify the implications for Identity and business development efforts broadly. (NACCA, 2023).

ACTIVITY — Evaluate the role of UNDRIP in promoting Indigenous rights and business development

The Native Women’s Association of Canada provides multiple accessible resources that may guide educators to work through their own intersections (Native Woman’s Association of Canada, 2022).

References

NOTE DOUBLE CHECK THAT ALL CITATIONS FROM THE CHATER ARE LISTED BELOW.

CONFIRM THAT ALL REFERENCES ARE ALSO CITED IN THE CHAPTER.

Bastien, F., Coraiola, D. M., & Foster, W. M. (2023). Indigenous Peoples and Organization Studies. Organization Studies, 44(4), 659-675. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221141545

Bryman, A., Bell, E., Mills, A. J., & Yue, A. R. (2011). Business research methods: Canadian edition. Oxford University Press

Department of Justice Canada. (2020). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/un_declaration_EN1.pdf

Government of Canada. (2024, June 20). Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/index.html

Indigenous Procurement Working Group. (2021). Defining Indigenous Businesses in Canada: Supplementary Perspectives from the Indigenous Procurement Working Group. https://nacca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/5a.-Defining-Indigenous-Businesses-Supplementary-Perspectives-Finall-English.pdf

Kesler, L. (2020, February 10). Aboriginal Identity & Terminology. First Nations Studies Program. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/aboriginal_identity__terminology/

Montpetit, I. (2011, May 30). Background: The Indian Act. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/background-the-indian-act-1.1056988

NACCA. (2023). Engagement Findings for a National Indigenous Business Definition. https://nacca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Indigenous-Business-Definitions-Engagement-ENGLISH-March-2024-ID-20173.pdf

Native Woman’s Association of Canada. (2022). Native Woman’s Association of Canada Research Toolkit. https://www.nwac.ca/assets-knowledge-centre/SPARK-NWAC-CRGBA-TOOLKIT-2022-EN1-3-Feb-15-2022.pdf

- Canadian context. ↵

treaties signed by First Nations and the British and Canadian governments between 1701 and 1923.

11 treaties signed by the First Nations peoples and the reigning monarchs of Canada between 1871 and 1921, providing the settler government with large tracts of land in exchange for promises that varied by treaty.

Ongoing work to implement modern treaties and self-government agreements.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is a comprehensive international human rights instrument on the rights of Indigenous peoples around the world.

Section 35 is the part of the Constitution Act that recognizes and affirms Aboriginal rights. The Canadian government did not initially plan to include Aboriginal rights so extensively within the constitution when the Act was being redrafted in the early 1980s. Early drafts and discussions during the patriation of the Canadian Constitution did not include any recognition of those existing rights and relationships, but through campaigns and demonstrations, Aboriginal groups in Canada successfully fought to have their rights enshrined and protected.

It is important to understand that Section 35 recognizes Aboriginal rights, but did not create them—Aboriginal rights have existed before Section 35.

The term “Aboriginal” refers to the first inhabitants of Canada, and includes First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. This term came into popular usage in Canadian contexts after 1982, when Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution defined the term as such. Aboriginal is also a common term for the Indigenous peoples of Australia. When used in Canada, however, it is generally understood to refer to Aboriginal peoples in a Canadian context. This term is not commonly used in the United States.

“First Nation” is a term used to describe Aboriginal peoples of Canada who are ethnically neither Métis nor Inuit. This term came into common usage in the 1970s and ‘80s and generally replaced the term “Indian,” although unlike “Indian,” the term “First Nation” does not have a legal definition. While “First Nations” refers to the ethnicity of First Nations peoples, the singular “First Nation” can refer to a band, a reserve-based community, or a larger tribal grouping and the status Indians who live in them. For example, the Stó:lō Nation (which consists of several bands), or the Tsleil-Waututh Nation (formerly the Burrard Band).

The term Métis refers to a collective of cultures and ethnic identities that resulted from unions between Aboriginal and European people in what is now Canada.

This term has general and specific uses, and the differences between them are often contentious. It is sometimes used as a general term to refer to people of mixed ancestry, whereas in a legal context, “Métis” refers to descendants of specific historic communities. For more on Métis identity, please see our section on Métis identity.

This term refers to specific groups of people generally living in the far north who are not considered “Indians” under Canadian law.

Self-governance is the control of a group's affairs by its own membrers. Some Aboriginal groups in Canada have successfully negotiated self-government agreements with the Government of Canada; howerver, an Aboriginal community may exercise self-governance even if it hasn't signed a self-goverment agreement.

All Indigenous peoples have rights that may include access to ancestral lands and resources, and the right to self-government.

The complex and multifaceted sense of self that Indigenous individuals and communities hold, which includes aspects of culture, heritage, legal status, and community ties.

A Canadian federal law that governs matters pertaining to Indigenous peoples, including their lands, resources, and governance. It has significant implications for Indigenous business practices.

The ongoing process of acknowledging and addressing historical injustices and harms done to Indigenous peoples, with the aim of fostering improved relationships and equality.

Reserves are held by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of the respective bands for which they were set apart, and subject to this Act and to the terms of any treaty or surrender, the Governor in Council may determine whether any purpose for which lands in a reserve are used or are to be used is for the use and benefit of the band.

Feedback/Errata